Chapter One Introduction

Chapter Twelve Story Tellers

Appendixes

Shavers Fork Coalition

Matthew Branch with his VISTA supervisor Ruth Blackwell Rogers, 2002

First and foremost I’d like to thank my family and friends for their love and support and guidance throughout the various processes of creating this book. I am nothing without you all.

Beyond that, I’d like to thank all of the various storytellers who shared their live experiences with us, and made this book a reality: Jack and Doris Allender, Jim Bazzle, Londa Bennett, Lorraine Burke, Roy Clarkson, Carl Frisckhorn, Terry Grimes, Boone Hall, Ed Broughton, Tom Broughton, Virgil Broughton, Earl Cane, Cheat Mountain Club visitors, Alice Cooper, Devane Cussins, Pat Dugan, Springy Galford, Harvey Hamrick, Chuck Hayhurst, Zach Henderson, Lillie Mae Isner, Al and Ann Krueger, Steve Lambert, Harry Mahoney, Phil Miller, Shawn Mullenex, Henry Nefflen, Grace Nelson, Hayward Phillips, Jim Phillips, Dorie Powers, James “Jim” Propst, Frank Proud, Henry A. Ridgway, Buck Rowan, Bud Sanders, Grace Schaffer Gainer, Hazel Shaffer Phillips, Johnny Sharp, Wanda Powers Sharp, Calvin Shifflet, Mariwyn McClain Smith, Jim Snyder, Bill Thorne, Peck Vance, Jerry and Jean Wagener, Lucille Ward, Kenny Watson, Bert Weese, Duane “Leo” Weese, Jim White, Agnes Smith Wilmoth, Martin and Jean Wilmoth, and Stanley Wooddell.

Also, I’d like to thank the Office of Surface Mines and Volunteers In Service To America for establishing the “Coal-country watershed team” which made this position available and provides understaffed watershed organizations with fresh blood.

Canaan Valley Institute was also very supportive in getting this project off the ground, especially by providing us with the funding for a professional editor. Much gratitude goes toward the Appalachian Forest Heritage Association for supplying us with funding for the design and layout for the book. Numerous other organizations provided additional information and support: The Monongahela National Forest, The Nature Conservancy, the D.D. Brown Collection at the West Virginia University Library.

Many thanks to interviewers Hugh Earnhart, Rebecca Rogers, and Terry Ruthrauff. Of course, the chapter on Spruce would have been largely incomplete without the work of Phil Miller who generously donated his interviews to the project. The person who originally conceived the project, Karen Sutton, also went out and performed the first interviews; I and anyone who enjoys the book is deeply indebted to her.

I’d like to thank Corinna McMackin, Cindy Phillips, George Constantz, Sara Pritchard, and Roy Clarkson for their help with editing and double-checking facts and figures. Harriet Emerson performed the biggest chunk of editorial work, and without her exacting eye, this book would likely not be in print today.

Additionally, I am much indebted to my supervisor, Ruth Blackwell Rogers and her family. Ruth went above and beyond the role of boss and became a true friend and surrogate mother for me.

I know that I am leaving people out. There were so many wonderful experiences that I had while I was working on this project, from staying at Cheat Mountain Club to finding hidden swimming holes. There were also numerous interviews that never made it directly into the book -- much thanks goes to those people as well. The storytellers are truly just the tip of the iceberg of all those who contributed their time and energy to this project.

Lastly, I’d like to thank Hanu for being the keeper of my sanity through all of this, good boy.

-Matthew Branch

“My grandmother was a Shaffer but Shaver is the other name. Back then they didn’t have too much education, and they just spelled it the way it sounded—same with Schaeffer Beer. They’re all the same bunch.”—Jim Phillips

In December of 2001 I graduated from the University of Wisconsin with a major in Anthropology and a minor in Folklore. After working for a small furniture-building shop for a few months, I searched for a job that would use my college experience. My professor James Leary forwarded me an email calling for applicants for a public-sector position in West Virginia. It was through Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA), which is part of the umbrella organization, Americorps. Americorps and its programs pay people a small living stipend in exchange for a year of volunteer labor with a nonprofit organization. VISTA usually focuses on urban poverty and similar issues, but had teamed up with the Office of Surface Mining (OSM), for a special project in the Appalachian coal country. I was to be working specifically with a small watershed organization called the Shavers Fork Coalition (SFC). At the time, I knew little about VISTA, and nothing about OSM or watershed organizations. However, it was the job description that had caught my interest. The project was to collect oral histories and personal experience narratives in order to celebrate the local history and folklore of the Shavers Fork watershed. Suddenly, the “skill set” that I had acquired as an undergraduate had the potential to land me a job.

Growing up, I had always loved to be outdoors. Nature called to me, and I spent much of my youth in Wisconsin hunting, fishing, hiking, tree climbing, or doing whatever else might bring me out into the wilds. This job looked like an opportunity to combine my love of interacting with people and learning more about culture with a chance to experience the outdoors in a part of the country I had never before visited.

So I applied, and I got the job. By the end of the summer, I packed all of my worldly possessions in the back of my pickup truck, put my newly acquired puppy Hanu in the passenger seat and headed east, ready to meet people, listen to their stories, and compile them into a book.

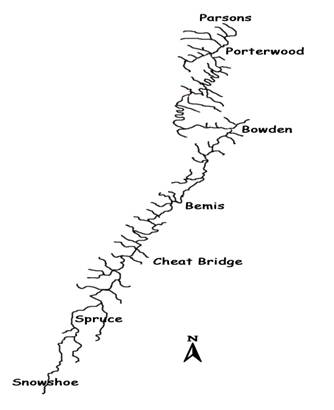

One of the first items given to me upon arriving at my new home in Elkins was a map. Not really a single map, but a collage of small quad maps glued together to produce one long map of the land immediately surrounding the Shavers Fork, eighty-four miles long, from its headwaters at Snowshoe Mountain Resort to its confluence with the other fingers of the Cheat River in Parsons. The map of this very long very narrow watershed was itself over twenty feet long.

During my first weekend in

West Virginia, my supervisor invited me to a

potluck in a campground on the river. I took my initiatory swim in the river,

while my puppy Hanu took his first swim ever. After swimming, the group ate and

sat around until well after dark telling stories, singing, reciting poetry, and

generally carrying on. When I got home, I looked on the long map and found the

exact place Hanu and I had swum. While there was no name on the map for this

place, I now knew it to be Cheat River Campground. This was my first real

experience of the Shavers Fork watershed and its inhabitants.

During my first weekend in

West Virginia, my supervisor invited me to a

potluck in a campground on the river. I took my initiatory swim in the river,

while my puppy Hanu took his first swim ever. After swimming, the group ate and

sat around until well after dark telling stories, singing, reciting poetry, and

generally carrying on. When I got home, I looked on the long map and found the

exact place Hanu and I had swum. While there was no name on the map for this

place, I now knew it to be Cheat River Campground. This was my first real

experience of the Shavers Fork watershed and its inhabitants.

Mule’s Hole, above Bemis, late 1990’s. Photo courtesy Ruth Blackwell Rogers.

Some time later, a very different thing happened with the long map. I found a site named on the map, but the only things there were some old foundations of a mill. For most people in West Virginia, the ghost town of Spruce no longer holds any meaning. However, an entire chapter is devoted to Spruce in this book, because there was a wealth of experience in this remote place, once the highest town east of the Mississippi. For the people who grew up there, Spruce is still a place, full of memories and stories. Other once-bustling towns and lumber camps no longer exist on the landscape but as the months progressed they appeared vividly in stories told to me in interviews.

Over the course of the next year, the map became filled with markers – named and unnamed - of my experiences on the watershed. The map became a mosaic of stories. Meeting interesting people, sitting on porches and in kitchens listening to their stories, helping researchers tag brook trout in First Fork, downhill skiing at Snowshoe, hunting deer near Bowden, digging ramps, and checking out dozens of swimming holes were just some of the experiences that added to my personal depth of memories and tightened the bond between the Shavers Fork watershed and myself.

My VISTA supervisor Ruth Blackwell Rogers describes the Shavers Fork Coalition’s intentions for this book:

Coal

and timber extraction on the watershed during the first half of the 20th

century polluted the river and damaged the forest; associated timber camps,

towns and railroads boomed then largely disappeared. As aquatic and plant life

began to return, and the area began to attract outdoorsmen, conservationists,

researchers, and state agencies have focused more kindly

attention on the

Shavers Fork watershed. In 1996 the Shavers Fork Coalition was formed,

“dedicated to the ecological health, natural appeal, and cultural heritage of

the Shavers Fork watershed.”

attention on the

Shavers Fork watershed. In 1996 the Shavers Fork Coalition was formed,

“dedicated to the ecological health, natural appeal, and cultural heritage of

the Shavers Fork watershed.”

The history of the Shavers Fork watershed during the 20th century is a nutshell history of logging and railroads in West Virginia. It’s all there: timber boom, railroad building, town development, waning of timbering and towns; coal mining, waning of coal and freight railroading; re-growth of forests, changing logging practices, Forest Service timber management; impacts on natural and human life; and how people lived through all these changes.

Shavers Fork Coalition decided to gather stories of how people lived through all these changes, in other words, stories of life on Shavers Fork. We wanted to let the “voices” speak for themselves in the form of a book. Author Matthew Branch’s fresh eyes – which had never before seen West Virginia – gave him a good perspective from which to write a book relatively free of pre-conceived notions or expectations. We wanted a “snapshot” of life on the watershed, told in the words of railroaders, loggers, farmers and farmers’ wives, hunters, Forest Service employees, preservationists, postmasters, vacationers, and fishermen. Matt developed relationships with numerous people on the watershed, interviewing those who promised to be good storytellers. He also collected photographs, memoirs, newspaper articles and logbook entries. With these resources and local history books, the history of the area came to life of its own accord, with little need for narration. The result is an informative book that paints a lively picture of life on Shavers Fork in the 20th century.

Shavers Fork Coalition hopes that by bringing to life the watershed’s voices and history, this book will significantly encourage sustainable use of our resource -- the forests, streams and wildlife -- and will foster interest in the cultural history of the watershed.

Shavers

Fork

River is named for settler and Indian fighter

Henry Shaver who migrated to the area in the late eighteenth century. A grave

marker beside Alpena Road on the way to Glady and Bemis states that Henry

Shaver tried to settle in the morning shadow of Cheat

Mountain

but Indians killed him.

grave

marker beside Alpena Road on the way to Glady and Bemis states that Henry

Shaver tried to settle in the morning shadow of Cheat

Mountain

but Indians killed him.

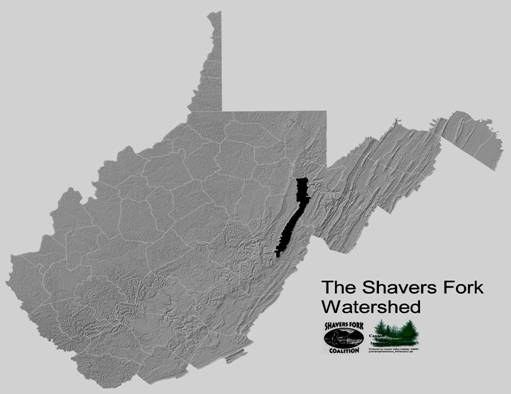

Nestled in the West Virginia highlands, the Shavers Fork flows eighty-four miles across three counties, from the headwaters near Snowshoe Mountain Resort in Pocahontas County, through Randolph County, to the beginning of the Cheat River downstream of Parsons in Tucker County. Locals often refer to Shavers Fork simply as “Cheat River.”

Stories about deceptively deep holes and walls of water earned the Cheat River a reputation as a dangerous place. The Cheat is commonly believed to have earned its name because it cheated so many people of their lives. It is also possible that the river draws its name from a French explorer named Cheate, a grass called cheat, or an Indian name. In any case, the first story is the stuff of legends and circulates more often.

Two long mountains press against each other to form a fold in the landscape. Cheat Mountain lies to the west, and Back Allegheny and Shavers Mountains form the eastern ridge. This complex is commonly referred to as Cheat Mountain, and it harbors many of the highest points in West Virginia, including Bald Knob, the second highest at 4,860 feet above sea level. The longest tributary of the Cheat River, Shavers Fork winds between the ridges of these mountains.

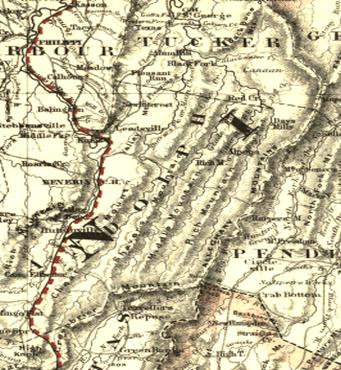

Railroad map from the 1800’s. Source of Shavers Fork is in extreme lower left corner.

Shavers Fork is the coldest running stream in

the state and host to more than fifty threatened and endangered species such as

the

Cheat Mountain Salamander, the West Virginia northern flying squirrel,

snowshoe hare, goshawk, Bartrams serviceberry, balsam fir, and Canada

honeysuckle. (Clarkson) The upper segment of the river runs through the middle

of the watershed from the headwaters at an elevation of almost 4,600 feet for

more than twenty miles. The gradient then increases drastically, dropping 1,000

feet between Cheat Bridge

and Bemis, fifteen miles downstream. Isolation and elevation protected

the land from large-scale logging until the early twentieth century and have

also protected most of the land from industry and development. Large parts of

the watershed remain relatively wild land.

Cheat Mountain Salamander, the West Virginia northern flying squirrel,

snowshoe hare, goshawk, Bartrams serviceberry, balsam fir, and Canada

honeysuckle. (Clarkson) The upper segment of the river runs through the middle

of the watershed from the headwaters at an elevation of almost 4,600 feet for

more than twenty miles. The gradient then increases drastically, dropping 1,000

feet between Cheat Bridge

and Bemis, fifteen miles downstream. Isolation and elevation protected

the land from large-scale logging until the early twentieth century and have

also protected most of the land from industry and development. Large parts of

the watershed remain relatively wild land.

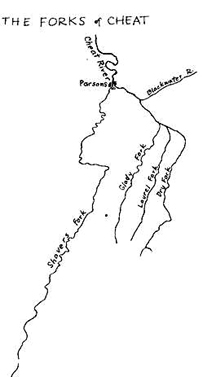

The Shavers Fork is one of the five “fingers” that form the headwaters of the Cheat River. The other forks of the Cheat are the Glady, Laurel, Dry, and Black forks. These flow fairly close together south to north and on a map look like fingers of a hand.

U.S. Route 219, several miles to the west, parallels the Shavers Fork north from Slaty Fork through Valley Head, Huttonsville, Mill Creek, Valley Bend, Beverly, and Elkins. Route 33 crosses the Shavers Fork at Bowden, where the river heads west for several miles before continuing roughly due north. The U.S. Forest Service’s Stuarts Park Recreation Area is located at this intersection.

The Monongahela National Forest is the largest landholder on the Shavers Fork watershed. It owns more than 65 percent of the land. Much of the watershed is open to the public, leaving individuals responsible for maintaining the area’s health and beauty.

Excerpt from “Face on the Wall,” by Jim Snyder

Jim Snyder, a kayaker who has traversed the entire length of the river, shares a vivid description of Shavers Fork on one of his journeys from Cheat Bridge to Parsons:

I’d like to run you quickly down the Shavers Fork. I put in with light gear and a fast boat at dawn near Cheat Bridge, where Route 250 crosses the Shavers Fork of the Cheat at the highest easily accessible point. For the first couple hours I work down toward McGee Run through shallow riffles constantly nibbling for attention. The land here is high and flat, and the river is crystalline but hurried. Fishermen are ubiquitous and quietly busy happily waiting.

It was logged here around the turn of nineteenth the century. Vast realms of spruce and softwoods lay down for sharp saws of manifest destiny. The forest now looks plump and full, and entire chunks of trees and sod occasionally slough into the riverbed, releasing from a rocky substrate. But the softwoods are few and scattered now, and yellow birch predominates. There are often large branches poised vertically in the soft ground of flat shore along the river—evidence of the wind’s searching power and the irresolute upper reaches of the trees.

Past McGee Run, I rarely see a person. The next couple hours to the High Falls of the Cheat are a treat quietly breezed through. The last mile before the falls features bedrock encroachments as the riverbanks become steep. The river begins to take on a darker and more serious demeanor but the falls vault brilliantly in the morning sun in a multifaceted plunge. An easy portage on the right brings me to the “mystified” pool at the base.

My chief concerns lie in the entire upper 90 percent of the river, the next few miles to Bemis. There’s a portage and blind pushy drops, which often feature new trees. I like to gently paddle through the shallow shoulders of the drops if I can.

Going under the Bemis Bridge is only a slight relief. There are still drops ahead that can spill even a careful rider. But before long, the river calms its adolescent angst, and I develop a steady but fast pace through one of the more remote sections. I won’t see anyone for the next couple hours. I stay busy dodging rocks, evading shallows, and respecting the ever-increasing numbers of flood-torn trees. The river hurries on as always, but now—this moment—it has an appreciative rider.

Suddenly “civilization,” Bowden, breaks the spell. Huge newly cut trees on the right on the very brink of the river speak of the nearby houses. It seems everyone wants a house that is the farthest up into the wilderness. They all want to be flood and bear bait. At Bowden, a bridge accompanies a four-foot-high dam, both accommodating great numbers of fishermen. The next hour of river time belongs to them. All the way down to the Old Route 33 bridge, I’ll never be out of sight of the fisherman who apparently love crowding each other.

There’s a nice store at the Old Route 33 bridge. It’s a good place to pick up a late lunch and last minute items for dinner at camp that night. Then “POOF!” back into the spell. Yes, there’s a house here and there and occasionally a passerby, a farm, two bridges. But the hills now mount to an impressive height, and the woods pile on each other as far as you can see.

I can barely hear a road, and the smells of the forest reach me on threads of a wind that can howl like rogue jets on distant unseen hilltops. Mile on mile, curve after curve, woods upon woods; the spell deepens. I admire how a few pines collect aesthetically in the deciduous forest, and a cliff face shows itself hiding dark in the hillsides.

It’s beautiful, and I pause to put it into words. But words won’t fill the space, and time pulls me into the deepest section of this stretch. The river turns serpentine with bottomless empty fishing holes at each big bend. The water now is too acid to support many fish, and I seldom see any in this section. Insidious acid rains have subdued this neighborhood.

Here the river displays a quiet but restless integrity. It rambles on and on for five hours to Parsons. Now it is choked with massive debris piles from the 1996 and 1985 floods. There are unique artifacts like a six-foot-tall 500-pound tire in the middle of nowhere and a discarded motorcycle half inundated at the base of a cliff.

Soon roads peek into my wilderness, and nice little houses spot the shore. I can only think, “Don’t blame ‘em one bit (but I hope they don’t have friends),” and move on. After a short forever, a cluster of houses appears on the floodplain, and soon after the Kingsford Charcoal Plant looms in the floodplain on the left, nervously barricaded behind an unimpressive floodwall. The heat and flames exploding from the huge smokestack are reminiscent of the Wizard of Oz, but I’ve never smelled the least speck of smoke or seen any degradation of the water here. Yet the mountains of logs and sawdust awaiting American grills illustrate the plant’s cost.

Now trailers crowd in and small houses. Soon my passage through Parsons will go by unnoticed by the locals. The Shavers Fork lies behind me, but it has left a beautiful quiet mark on my soul.