Chapter Three

“Logging is a great way of

life.”

—Terry Grimes

Logging:

Wood Hicks on the

Mountain

Water

Powered Sawmills

It wasn’t too long before the Shavers Fork saw its first mills, which

were put in around 1845, one at the foot of Taylor’s Run in Bowden and the other

in Parsons. The mill at Taylor’s Run was just a sawmill, while the one in

Parsons was a saw and gristmill. Abraham Parsons built the Parsons mill, but it

was destroyed in the flood of 1857. He then rebuilt it in 1859, but did not

rebuild the gristmill. After that, ownership of the sawmill changed hands

several times before the building was torn down in 1933 (D.D. Brown Collection).

In 1858, Allender mill was built. Jack Allender related the following

story about it:

At the lower end of our place, I reckon my granddad had an up

and down saw. We got the blade off of it—the teeth were that long (makes sign

of two inches)—it was water operated. They claimed they could roll a log up

on it, and they had a big wheel like a gristmill, and it run that sawmill. They

said you could put a log on that and go and eat your dinner, come back, and the

board was done.

These mills were all powered by water, which

turned a wheel around, which in turn moved the saw up and down. They were

sometimes jokingly called “up today, down tomorrow” saws. This method was indeed

slow and produced approximately 500 board feet per day, although it was less

backbreaking than doing it by hand. The next leap in technology arrived with the

Civil War. Fort

Milroy, located on the frigid top of Cheat Mountain near Cheat Bridge, had a

small steam-powered circular sawmill, which was another vast improvement.

However, it was not put to much use, as the soldiers worked more on survival

than logging.

River Drives

River drives were to be the next

interesting, albeit short, piece of Shavers Fork history. According to J.L.

Goddin, a man by the name of Goolick took out some of the best logs in the

1880s, mostly poplar

trees, and floated them downstream. Shortly after, W.S.

Dewing & Sons of Kalamazoo, Michigan, began buying up

much of the area around Cheat Bridge through a contractor named Col. A.H. Winchester and his wife, Ella (at

that time Cheat

Bridge was known as Winchester).

trees, and floated them downstream. Shortly after, W.S.

Dewing & Sons of Kalamazoo, Michigan, began buying up

much of the area around Cheat Bridge through a contractor named Col. A.H. Winchester and his wife, Ella (at

that time Cheat

Bridge was known as Winchester).

Cheat Bridge: A rare picture of the once thriving community at

Cheat Bridge. Notice the

covered bridge that was used at the time. This photo was taken during the era

when the road was still known as the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike. It was also

the headquarters for W.S. Dewing & Sons on Cheat

Mountain. Photo courtesy Cheat Mountain Club

This was the first large-scale commercial

logging to take place on the watershed. Logs were marked with a W for

Winchester and floated all the way down to Point Marion, Pennsylvania. There

was even a house boat on the Shavers Fork built near Taylor’s Run that housed

fourteen men for their trip down the river with the logs. This outfit lasted for

three or four years in the early 1890s, and the effects of it can still be seen.

Rocks were blasted in the upper Shavers Fork to clear the river, and splash dams

were created to control the spring flows (D.D. Brown Collection).

1899 Dewing & Sons sold the land to J.G. Luke of

Brooklyn, New York, for $585,000, which

was approximately $8.65 an acre, fairly costly at that time (Deike, p. 5). This

price also included a sawmill and planing mill at

Point Marion, Pennsylvania, as

well as all the logging equipment already there.

Johnny Pulp

Logs Cheat Mountain

William Luke and his six sons, directors of the newly formed West

Virginia Pulp & Paper Company, then proceeded to develop the area, putting in

logging camps as early as 1900. Life in the camps was rough. Men got up before

dawn and worked until dark. But their pay was fair, and the food is reported to

have been great. Camps were identified by number, and as the camps moved, the

numbers moved with them.

-

WVP&P heads: Rare picture of the men behind the

West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company. Front row L to R David L. Luke, Emory P.

Shaffer (supt. Of the Cass operations), Samuel L. Slaymaker (sales Manager),

Thomas Luke, Harvey Cromer (land acquisition and surveyor). Back row L to R.

Richard Beaston (procurement manager), M. Otley (owner of McCall magazine),

William Luke, D. Talbott (company attorney), Allen L. Luke (in front of talbott),

and John G. Luke. June, 1909 at the cheat mountain clubhouse> four of these

men were company presidents: William Luke, 1888-1905; John G. Luke, 1905-1921;

David L. Luke 1921-1934; Thomas Luke 1934-45.

Photo and Caption courtesy Roy

Clarkson.

Payday was once a month, and Terry Grimes told

me that his grandfather used to put  a twist in his suspenders for each day he

worked, so he knew he was getting paid fairly. Some of the evidence from those

little hamlets comes from the news reports that some of the camps sent into the

Pocahontas Times to report on life in the camps. Full of wit and

at times difficult to understand, these letters from the camps offer insight in

the positive attitude held by the wood hicks. Keep in mind that the first

article was written July 4, 1901:

a twist in his suspenders for each day he

worked, so he knew he was getting paid fairly. Some of the evidence from those

little hamlets comes from the news reports that some of the camps sent into the

Pocahontas Times to report on life in the camps. Full of wit and

at times difficult to understand, these letters from the camps offer insight in

the positive attitude held by the wood hicks. Keep in mind that the first

article was written July 4, 1901:

A logging camp on the move on Cheat Mountain. This was one of the Bemis

logging crews.

In back a log loader can be seen. Photo courtesy

Keith Metheny from his

grandfather, Clair Metheny

Cass, Camp

#3

Our camp is on the headwaters of

Cheat River. The railroad (log road)

comes within two and a half miles of our camp and will come on to the camp next

fall some time. The grading is completed this far now.

We had iced tea and ice cream last Sunday made from ice gathered

out of the mountains up here within a mile of our camp.

H. R. Warner is our foreman, and is getting good work done.

Fred Beard is scaling the lumber as it is cut.

“Old Smoke” is here, went fishing the other day, but didn’t catch

any fish. Says there are no fish in this part of the country.

“Paul Bunyan” is filing six saws and going to see six girls. Keeps

him busy too.

Mr. Shaffer, the superintendent, comes to see us frequently.

Mr. Cass paid us a visit last week.

Henry Dawson and a party of fishermen from Hinton passed here on

their way down to Cheat Bridge some

time ago.

Several of the boys are going out for the Fourth, but about as many

come in as go out.

James Kirkpatrick is our cook, and Auburn Pyles, the “schoolmarm,”

is cookee.

With best wishes for a hot time the

Fourth, we are, Uncle Waldo

Spruce News,

Camp #2

No. 2 Camp is located near the thriving hamlet of Spruce, which

consists of a store, post office, and a number of magnificent dwellings. D.J.

Tabor, foreman, has a full crew of about seventy-five men. Jud is herding

Arbuckle signatures to exchange to the Arbuckle Brothers for road monkeysand swampers.

Mr. Ed Hunter is the woods superintendent. He has been in the employ

of the West Virginia Spruce Lumber Company for over two years. He is a faithful

enterprising woodsman, liked by all. —Rosebud Jim

Lost, strayed, or kidnapped: a small road monkey about the size of a

man, weight 180 pounds, sandy complexion with red whiskers, disappeared from the

road monkey navy on January 31, 1903. When last

seen (he) was headed toward Huntersville. Any information leading to his

whereabouts or apprehension will be cheerfully accepted by the Road Monkeys

Lodge.

The teamster and the road monkeys had it round and round, the

teamster put the road monkey down on the ground. —Snowball Bill (Pocahontas

Times, February 12, 1902)

Spruce, Camp

#7

The snow is from three to five-feet deep. On the north sides it is

deeper than on the sunny southern sides. This is a wilderness of a place now as

the snow is so deep. One day it snows and possibly the next is sunshine. It

often threatens rain but cannot rain seemingly. We haven’t had any real cold

weather here this winter; the coldest it had been was about twenty degrees

below. The little spruce trees just bending down crowded with snow, making it

very disagreeable for men to go through.

John Hardy is our enterprising foreman. He has under his employment

seventy men. Edward Smith is our cook; Shorty Allman is one of his cookees;

David Smith is buck swamper with his gang; Wild Bill Smith is blacksmithing;

Johnny Eagan is barn boss and Lobby Hog and a fine one too. His work is keeping

the barn in good shape for the teamsters, and if a horse gets knocked out, he

looks after him. The Lobby work is keeping fire, cleaning up after the crew

turns out, filling the water barrel for the men to wash. He gets wood for the

cook stove. We burn coal in the Lobby Stove.

We have a beautiful habitation here. Our surroundings are shining

snow. The trains just look as if they are going through a cut all the way, as

the employees have shoveled the snow out on either side so often.

We are glad to have a post office so near our habitation. We have a

beautiful little town on the river now. The post office is still called Spruce.

There are several dwelling houses, a big store. A large mill has been built for

peeling pulp, cutting it in short blocks. They have fine machinery in it and are

contemplating adding more to it. Anyone who never saw such things, it is worth

their while to see it run. This would be an ideal summer resort as the air is

pure and cool.

The Spruce Company has at work four engines; three steam loaders,

and loads at various places with hooks. They are doing a big business and are a

big help to the people in old Pocahontas as they pay fair wages for labor.

All we need is a church at our town as it would be nice to pass off

the Sabbath days in attending religious worship.

I think our county court ought to look after the liquor traffic more

than they do, as the hog’s ears are still in operation. If our court has power

to stop them from selling, I think they should do so or grant license to some

good man and let the county have the benefit it (Pocahontas Times,

March 9, 1905).

John Barkley, teamster, with team and trail of

logs, Cheat Mountain, WV Pulp & Paper Company. Photo courtesy Ivan Clarkson.

Spruce and

Cass Emerge

West Virginia Pulp & Paper was responsible for forming the towns of

Cass and Spruce, both of which they established from the ground up. Cass was a

lumber mill town, and Spruce had an “unbarker” mill, which supplied pulpwood to

the paper mill in Covington, Virginia.

Rev. W.W. Sutton, in his memoirs written in 1944, recalls early logging up on

Cheat

Mountain:

When the West Virginia Spruce Lumber Company began operations on the

head of Shaver’s Fork, H.F. Cromer was employed as scout. No doubt he was the

man best fitted for such a job, and granting that all accounts were true, he had

many an interesting experience with both man and beast in his travels through

those woods.

The Greenbrier Division of the C & O [Chesapeake

and Ohio] had been completed up as far as Cass. Late in the year 1900, a

standard gauge switchback road had been completed up Leatherbark, and it crested

Cheat Mountain within 200 yards of Shavers Fork Camp, No. 2, built late in December.

This scribe went up that mountain in the afternoon of

January 2, 1901 and met the first load of

spruce logs coming down that had been cut near the top.

Ed Hunter was boss at Camp 2. We went to work

the next day. The railroad track was being laid across the top. Ed Hunter put me

to swamping for two days, then to rolling skid

with Henry Galford. They were skidding logs right on the top of this low place

in the mountain. The men slept the first few nights in bunks built of boards

from which the ice had not yet been melted. I took a severe cold from it. The

first week of April 1901, there fell a soft snow on Cheat more than three feet

deep.

Sacking the

Slide and Southern Manners

Stanley Wooddell also wrote a memoir of his life, and he recalls a

fishing trip with his father where his father showed him the scars of the land

that held valuable lessons:

We fished down to what Dad called the rough and tumble landing at the

mouth of what we called the Slide Run. This run got its name from the two-mile

long slide from the railroad to the low place, now where the Snowshoe road

forks. Logs were hewn flat and cribbed up level as much as eight to ten feet

high, placed in a trough-like position, and held in place by long drift bolts.

Logs were decked along this slide, and when the weather got cold enough, water

was poured on the slide to make it slick.

The logs were rolled and slid down the long run

to the railroad. Sometimes a log would jump out of the trough and a crew of ten

men went along and lifted them back into the slide. This they called “sacking

the slide.” These men slid logs day and night—once for three days and nights

without a rest. The wages then were one dollar a day plus board. Two men carried

grub along the slide; one was my uncle, Grover Wooddell. They carried

five-gallon cans of coffee and a barrel of food strapped on their backs to feed

the hicks.-

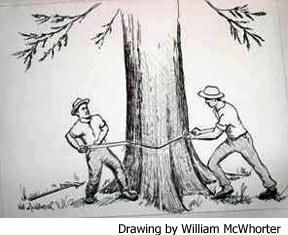

Loggers pause for a picture displaying the

tools of the trade; a crosscut saw, axes for notching a tree and bumping limbs,

mauls for driving wedges to assist in felling

a tree or to prevent pinching of

the saw, and a measuring stick for laying off logs.

Photo and caption courtesy

Roy Clarkson

The big log camp was built about half way up

the Slide Run, and a wagon road used to haul supplies and hay for the horses to

the camp. This road can still be seen in some places. The empty cans there

looked like a big sawdust pile at a country sawmill.

The men there were a rough and hearty bunch and

always ate with their hats on. A southern cook asked them to leave their hats in

the lobby when they came to the table. Everyone did except one big Canadian. He

said no tar heel would boss him. The cook took him by the ears and took him to

the lobby where the

Canadian picked up a poker and made for the cook, who took a

butcher knife from under his apron and told the big Canadian to come on in but

he would leave his head in his hat in the lobby. The camp boss, Lanty Cole,

separated them, but there was no more eating at the table with hats on.

Canadian picked up a poker and made for the cook, who took a

butcher knife from under his apron and told the big Canadian to come on in but

he would leave his head in his hat in the lobby. The camp boss, Lanty Cole,

separated them, but there was no more eating at the table with hats on.

Henry Nefflen recalls hearing about the importance of cooks

from his friend “Sparky,” “Sparky said how he was

17-18 years old and he was playing ball and his uncle got him and sent him off

to a logging camp, and he had to walk into them. And he would say that

everyplace paid about the same, and when you went into the camp you stayed

there, for months maybe. But you were there while you were working. So what

made men go to one camp or another was the cooks, and who was the good cook.”

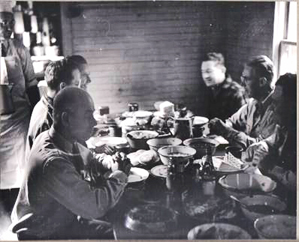

A cook and his “cookees” on Cheat Mountain near Spruce, 1910. These were employees of West Virginia Pulp and

Paper Company. Photo Courtesy Roy Clarkson

Log Camps and Wood Hicks

These early logging camps played a significant role in the history of

America, and their place has been lost to time. As Americans became more

mobile, the need to establish logging camps disappeared. Devane Cussins shares

memories from when he was a child visiting the log camps a little later, around

the 1940s:

disappeared. Devane Cussins shares

memories from when he was a child visiting the log camps a little later, around

the 1940s:

I loved to hang around the log camps and talk to

the wood hicks. Mr. Sager was the head cook at the camp at Spruce. You could

always get a big steak and biscuit sandwich, or some sugar cookies, and a big

bowl of chocolate pudding. Old log camps seemed to be built the same, and I

guess I had visited them all.

The lobby was next to the kitchen

with a big potbelly stove in the center of the floor

and benches all around the

walls. They would bank the stove at night. Find I can remember that I used to

get up real early in the mornings, I guess around three or four o’clock, take my

railroad lantern and go to the log camp. I would stoke the fire so it would be

hot when the wood hicks got up. Mr. Sager would give me a big bowl of oatmeal

and some sugar cookies when breakfast was ready.

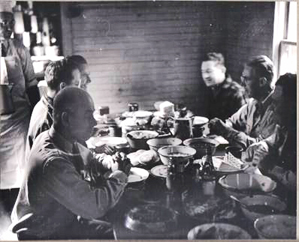

A rare picture of

mealtime in a log camp. This picture is dated September 1950, well after the

traditional log camps had disappeared. Courtesy Monongahela National Forest.

Then I would help the

drivers get the horses ready to go to the woods. We had to feed them, put the

harness on, and hook up the single or double trees. After everyone was off to

work, then it was time for me to go back home and get ready for school. Or, if

there was no school, sometimes I would go to the woods with the drivers and

watch the men cut trees and skid the logs down to the log landing. There I could

help knock the grabs

out of the logs, stamp each of the logs on both ends, then use a cant hook and

roll the logs over the bank into the pond. At first they had all horses. Then

later on, I remember there was a caterpillar or two. Sometimes I could ride on

the cat to skid the logs. (Grabs: i.e.

skidding tongs, a pair of hooks attached by links to a ring and used for

skidding logs.)

Then there was the loaders, to load

the logs on the flat cars. I could ride in the loader and shovel coal to keep

the boiler hot or just stand and watch. I loved to watch the loader operator

swing the tongs to the hookup man. He would catch the tongs, open them up, and

throw them at a log. It seems the tongs always stuck to the log he aimed at, and

then he would jump out of the way.

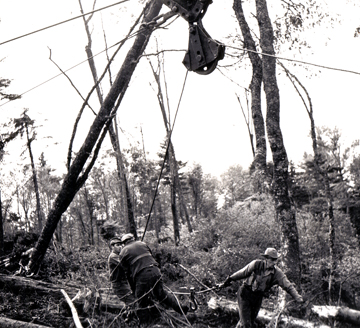

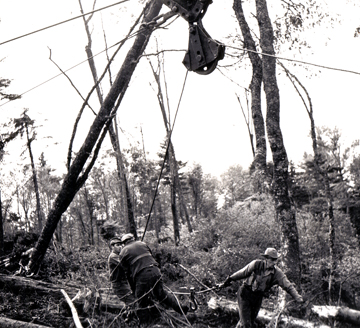

Next was the skidders. I could get up

in the skidder and watch all the maze of cables and pulleys as the trolley went

down the cable and came back up the mountain with a load of logs. Sometimes I

would go down the mountain to where the men were cutting the trees and watch

them hook up the logs. The bellboy had what looked to me like a giant clothespin

with two wires attached. Every time one of the loggers yelled a command to the

bellboy, he would squeeze the clothespin together. It would ring a bell inside

the skidder, and the skidder operator would sound the whistle on the skidder. I

was always careful to stay out of the way when the load of logs started up the

mountain, because they knocked down anything in their path. It was really

dangerous in the woods when they were operating.

Back at the log camp, I could visit

the saw shop and watch the filer sharpen the crosscut saws or watch the

blacksmith make horseshoes. Usually he would let me turn the crank on the forge

where the

metal was heated. Or I could turn the crank to the grindstone while

one of the loggers sharpened his axe.

metal was heated. Or I could turn the crank to the grindstone while

one of the loggers sharpened his axe.

In the evening when they brought the

horses back in from the woods, I could watch while they took the harness off,

then help feed and brush them down. All the horses had names like Nip, Tuck,

Dan, Mabel, Tom, and Jerry.

The Shay engines from Cass usually

came to camp once or sometimes twice a day to bring empty flat cars for logs.

And I think once a week there would be a boxcar with supplies for the camp and

whatever the wood hicks ordered, like cigarette tobacco for the roll your own

and chewing tobacco. All the loggers wore hobnail shoes. I think they called

them corks.

I remember one man named Thad Higgins

lived across the shay tracks from the log camp with his wife in a small shanty.

He would invite me to eat with them sometimes, and I always thought she made the

best beans and cornbread in the world. Sometimes if I ate there and then went

home and my mother had supper ready, if I said I was not hungry, my mother

always asked, “You been up there eating at that Thad Higgins place again?” -

A

steam skidder on Cheat Mountain near Spruce. The intricate rigging is

clearly seen as is the daredevil standing on top of the tower.

Photo and caption courtesy Roy

Clarkson

Skidders,

Bellboys, and Snakes

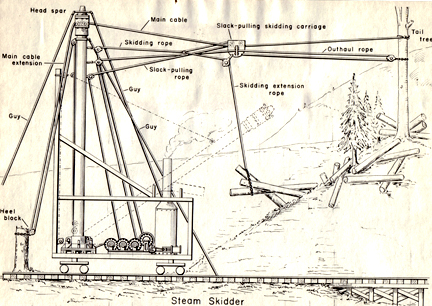

Technology constantly increased production;

changing the way the industry worked and the loggers lived. In the early 1920s,

steam skidders were first introduced that eventually replaced traditional horse logging. The last horse camp (Camp #95) pulled up camp on

Cheat Mountain in 1946. These

steam skidders left huge trenches in the earth; many can still be seen today.

They are being replaced now by diesel skidders and sometimes helicopters.

logging. The last horse camp (Camp #95) pulled up camp on

Cheat Mountain in 1946. These

steam skidders left huge trenches in the earth; many can still be seen today.

They are being replaced now by diesel skidders and sometimes helicopters.

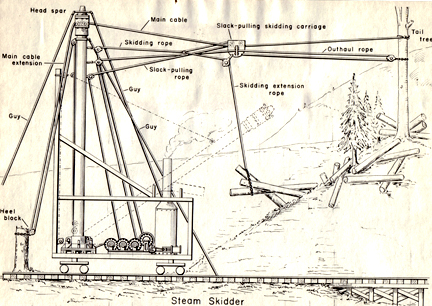

Harvey Hamrick explains how the overhead

skidders worked:

Let me give you a little history of how the

skidder worked. You see, you got these lines running back. You got an overhead

cable, which was an inch and a quarter cable. It was a great big cable. That’s

what they hauled the logs on. It goes way up in the air off the power of the

skidder and back into the tree on the top of the mountain—what they called the

tail tree. All right, then that cable would run through a block in this tree and

back down to the ground and snub it onto about three big trees or stumps,

whatever you got. You put it around one way, and back around this way, and back

around the other, and use what they called tie wire in it to fasten it down so

it can’t get loose, you see?

A sketch of an overhead skidder with attached lines. The dragging logs are

what caused the deep gouges in the ground that can still be seen today. Sketch

attributed to William A. Lunk, June 24, 1913. Photo

Courtesy Monongahela National Forest.

You’ve got other cables running, what they call

a re-haul, and you got a slack line. And it all runs back, and a buggy—what they

call a buggy—which is a contraption that runs on this cable with wheels in it,

and your cable comes through this. It’s got a big hook on it, and you’ve got

what they call chokers. It’s hooked on each log, you see, eight–ten–twelve logs,

whatever you get a hold of. They’re all brought in together when he picks up

from the skidder, which is maybe 500 or 5,000 feet away or more down at the

railroad.

Once these skidder lines went across

the top of this mountain and across another top and across another top and on

down where they had what you call five middle trees. Had to bring the logs to

this tree. All right. You had to change around and bring them to this tree;

change around, bring them to this tree; change around and bring them to this

tree, and then you went on in to the skidder: 11,000 feet, that’s what it was.

You see, to get your signals, you had

what they called a bell wire. It runs clear from the skidder up, and some had

what they called a bell ringer, a bellboy. He rang the signals, and you had

certain numbers. For instance, you wanted to pick up—all right, you took your

short, you just took your wires, which was bare wire, and do them like that for

shorts. Or if it was a long, you went like that. Whatever your signals were, it

rang the bell in the skidder, and he knew exactly what to do. Otherwise there

would be no way to run it without some signal some way.

They had four guys besides the man

that was handling the big cable. They had these chokers, which was a strand of

cable with a hook on one end and an eye on the other. And you just took that and

went right around your log and back-hooked the thing in that hook, and then

hooked all these—which may be eight or ten chokers—was hooked on these logs, and

you had to pull it under here, you see, to get the skid lines all hooked

together. And, of course, what you did, you just hooked one through, and it just

slid on the cable until you got your next and your next until you put it on

these bull hooks, they called them, which was down at the end of your skidding

line. When you’d get them all hooked, you’d ring into the skidder, pick up.

You’d pick up the load, and they’d pull them logs clear yonder in the air, maybe

40 or 50 feet or maybe thirty or whatever height the line was. Then they’d take

the logs into the skidder. So that’s the way and that’s just a rough idea of the

way it operated.

Harvey Hamrick relates a personal experience working on these overhead

skidders:

He put me doing blocks. A guy the name of Roger

Cotrell was on the blocks before me. He’s the one that got fired. He told me

about this black snake up in this tree, big old ash tree. I kind of believed

him. And I kind of didn’t believe him. But I didn’t know. I was just an oiler. I

oiled blocks.

Anyway, they put me to oiling blocks.

I had about fifty, and I had to oil them about . . . I’d get around at least

every three days. You had trees way up there to climb. You had climbers, you

know. And I had an old pair of climbers. The spurs were about that long, and

they would slip out, you know, you get way up in the tree. But anyway, this time

I kept going by this winch line block, and I said, “Oh, that doesn’t need any

oil.” So I kept skipping it.

One morning I thought:

what if the boss finds out I haven’t oiled this block?

He’ll get on me. I’d

better oil it. So I started up that tree. All I could think about was that black

snake he said was in it. It was a hollow tree, all right, so I got up, oh, I was

up about twenty-five feet. I took my rope up the tree. You know how you operate

with climbers: you’ve got this rope to keep in your hands, you see, and you just

keep flipping it up as you go up. I’m climbing, going up. All at once, I have to

flip it up and pull on it, and it felt like it was slipping.

I looked around, and

there was this old black snake. I had the rope right over him, and he was

licking his tongue right out in my face. I could have cut the snake in two if

I’d just had sense enough. Instead of that I set all holds loose down the tree.

I skinned the hide off my fingers, my chest, my legs, and hit the ground—ten

feet at least I dropped. The old snake went out one side of the tree, and I went

out the other. (Harvey laughs.) He wasn’t lying to me. And I’ll tell you one

thing, that block never got oiled while I was there!

September 1950. Second growth of native red

spruce about 50 years old at the head of Second Fork.

Railroad and Ligenwood

logging of the Mower Lumber Co. “Turn” of logs at skidder terminus of trip.

Photo courtesy

Monongahela National Forest.

Damaged

Land, New Spruce

Increases in technology had a great impact on

profits. Unfortunately, this also had an increased effect on the landscape, as

much of the new technology focused solely on how to increase board feet removed

per day and not on how to sustain the forest. Luckily for Cheat Mountain, West

Virginia Pulp & Paper had some forward thinking individuals at the time. Early

on they planted 25,000 spruce trees just off Shavers Fork in 1909 and 170,000

spruce and 2,000 yellow poplar in 1910 (PVB Collection).

Increases in technology had a great impact on

profits. Unfortunately, this also had an increased effect on the landscape, as

much of the new technology focused solely on how to increase board feet removed

per day and not on how to sustain the forest. Luckily for Cheat Mountain, West

Virginia Pulp & Paper had some forward thinking individuals at the time. Early

on they planted 25,000 spruce trees just off Shavers Fork in 1909 and 170,000

spruce and 2,000 yellow poplar in 1910 (PVB Collection).

Jim White describes what the landscape looked

like after the first phases of logging ended. After returning from World War

II, he goes on a fishing trip:

It’s right where that lake is at Snowshoe. So

right where those two little creeks came together, the railroad came across and

was on the east side. And then they had a line that didn’t follow the river

down. It gradually came up the east side of that mountain and came out about on

the top of the mountain. They may have had a skidder up on top of the mountain,

I don’t know. But this was a line that took it off the east side as well as the

west side. Right where it crosses the river there, that’s where we found that.

We went right down there, followed that old railroad grade to down where it

crossed the creek.

That was the most

despondent looking place I’ve ever seen in my life. They had just pulled the

skidders out of there the year before. You could hardly get to the river—just a

place here and there. The first time they logged that, nineteen hundred and two

or three, somewhere like that, they did it by horses. They select cut it. They

didn’t cut all of it, or I’ll presume they didn’t because they cut it again in

1942. I assume they left some sizeable logs in there. They used horses to get it

out.

I never saw a place where those skidders had worked, but I saw it up

there then. They had cut everything off ten feet above the earth. They cut

everything. There was nothing green left. It was worse than a battlefield. I

told my brother then, I said, “I’ll never be back to this place. It’s no use

coming here for fishing.”

You go up over that

mountain now, and you can hardly see where that logging had been. Stuff’s

growing back, and it’s green. Five, six years later, we decided to go back and

go fishing. It was amazing how that river got cleaned up. All of it had washed

out. Little spruce was coming up again, and it looked like a different country.

Good fishing. Maybe not what it had been one time, but it was good fishing.

Sept. 1950 Native Red Spruce second growth

timber about 50 years old at head of Second Fork, Cheat River, railroad and

Ligerwood logging of the Mower Lumber Co., Cass, W.Va. About 45 years since

original logging. “Chaker hookers” hooking chakers at the buggy (carriage).

Photo courtesy Monongahela National Forest.

Stanley Wooddell ruminates on the changes of

land use:

I stood at the end of the chairlift at Snowshoe’s Ballhooter

ski slope recently and watched the people riding the cable chairs up the

mountain. This reminded me of seeing the logs being hauled from one mountain to

the other by the big overhead skidders, sometimes as much as a thousand feet in

the air. But these are all gone, and the only thing there now is the Snowshoe

development operation on the head of the Shavers Fork of Cheat River.

From

Logged Land to National Forest

West Virginia Pulp & Paper later decided to sell their land on Cheat

Mountain and move elsewhere in the state.

Jim White relates:

For some reason, perhaps because of the Depression, West

Virginia Pulp & Paper sold all their holdings from

Cheat Bridge down to Bemis to the

National Forest. That was a considerable amount. They sold it all to the

National Forest. They also sold a tremendous amount of land up on Gauley

Mountain, but they still cut timber up there. Mower bought that company out in

1942.

For some reason, perhaps because of the Depression, West

Virginia Pulp & Paper sold all their holdings from

Cheat Bridge down to Bemis to the

National Forest. That was a considerable amount. They sold it all to the

National Forest. They also sold a tremendous amount of land up on Gauley

Mountain, but they still cut timber up there. Mower bought that company out in

1942.

South of Cheat Bridge, Mower Lumber continued to extensively cut the

timber off of the mountain for another eighteen years, mostly with skidders. It

was during this time that the first chainsaws were introduced on the mountain.

They were bulky, heavy, and not much quicker than crosscut saws, and weren’t

used much on Cheat Mountain

until the mid-‘70s.

Beavertail: A Disston “Beavertail” chainsaw

being demonstrated on Cheat Mountain, in 1948. The early models of chainsaws were

heavy, bulky and not much more efficient than the crosscut saws. It was

not until the 70’s until chainsaws gained much popularity in the area. Photo courtesy Roy Clarkson.

The last hook of an overhead skidder left the

mountain June 29, 1960. Mower Company then sold their holdings to a new owner,

who named his company “The Mower Company.” This outfit select-cut the top of

Cheat Mountain until the late

‘80s.

In April 1988, Senator Robert Byrd announced

the sale of the Mower Tract—40,745 acres—to the Monongahela

National Forest. This, of

course, wasn’t the entire area of the southern tip of the watershed. Carl Frischkorn, a former co-owner of Cheat Mountain Club, further explains:

The Mower Lumber Company then sold the land,

about 42,000 acres, to the Monongahela

Forest through a nonprofit group in

San Francisco called the Trust for Public

Land, but kept a reserve of

thirty million board feet of red spruce, which was interesting. The public was

against the sale because of the loss of tax base and jobs, so that was done to

keep some jobs for a bit, to help the transition.

Mower Lumber took out

logs by truck until 1993 at which time the Monongahela

National Forest placed a

ten-year rest period on the area. (Clarkson II, p. 95)

Other

Logging Companies

Johnny Pulp was not the only outfit working the Shavers Fork. After

the Civil War, logging company contractors approached many farmers to sell their

hillsides to the lumber companies for cash. This prospect seemed good to the

largely subsistent agriculturalists who until that point had bartered for most

of what they needed but could not produce themselves.

Montes, a Company Town

There were many companies on the

watershed—Parsons Pulp & Paper, Bemis Lumber, Cheat River Lumber Company, J.M.

Bemis & Son, Coketon Lumber Company—to name a few. D.D. and M.M. Brown headed

one such company. This was another family business. They owned a mill in Elkins

and the town of Montes, located several miles downstream from Bemis and now

nothing more than a ghost town. After the Browns purchased 2,000 acres of virgin

timber in the area and contracted to have a bridge built “strong enough to carry

the heaviest Western Maryland Railway Company engine then in service,” the town

of Montes was born.

In 1905, the Browns brought a circular mill in to quickly saw lumber

for the camp and millhouse, etc. After this, a complete eight-foot Giddings and

Lewis Manufacturing Company band mill was built, and millwrights were brought

into service. This area produced 44,800,000 board feet of lumber, which

averaged 22,000 feet per acre. This was an amazing amount, considering that the

spruce and mixed hardwood forests today would probably produce closer to

10–12,000 feet per acre. The mill at Montes averaged 52,000 feet per day, and

88,000 feet was the record for one ten-hour workday. This means that on average,

the operation in that area cleared two-and-a-half acres of woods in a day, four

acres on the best day! The company recorded that it took out approximately a

quarter spruce wood, a quarter hemlock, and half mixed hardwoods.

Montes Mines in 1998

From the log Mark Tracy kept during his

inventory of the West Virginia Central Railroad by rail-bike

June 12-8hr-8mi.

Although it is raining I go to Bemis with hopes of

capturing GPS data from MP 43

to MP 47.

In Mile 44 I find the old Montes Spur and the remains of

the bridge. The Montes Spur at one time crossed to the east bank of the Shavers

Fork at this point. Of the three bridge foundations only the one on the west

bank remains standing, the other two have been overturned by the river. There

is a camp visible on the east bank of the Shavers Fork.

Within sight of MP 45 there is the remains of an old brick

structure. This structure is made of firebrick and is double walled. I assume

it is a coke oven. Several years ago I was exploring the mountain above this

point. Approximately 600 vertical feet above the ruins is an old road that goes

by the adits of several abandoned coal mines. There are cones of dirty red gob

below the entrances. The road then led to a point on the ridge directly above

the ruins and from there a scar led straight down the fall line to the ruins. I

assume the coal was moved by gravity from the mines down to the railroad,

probably with an incline such as was used at the

Hopkins

Mine.

Another Clue to the Past

June 8-9hr.-15mi.

I go to McGee Run….Across the river from this point lies

the WVCRR. I must ford the river twice; first with the

GPS equipment, tool kit, lunch,

etc., and second with the rail-bike. The riverbed is 50m wide at this point.

The water is only knee deep but the crossing is treacherous due to the slick

brown slime that covers everything under the surface of the water.

At MP 57. For the second time I note an apple tree as a

GPS Point. An apple tree is

a non-native species along the upper Shavers Fork. They only grow where they

have been planted and they have only been planted in places where people have

spent a considerable amount of time. An apple tree shows where there used to be

housing for a logging camp, a mine, or a railroad section crew. When I find an

apple tree if I look around I will usually find the remains of these work camps,

i.e., some square stones that were foundations for their buildings, the remains

of an old railroad siding, a spring, metal junk, and a pile of ketchup bottles

and mustard jars. These sites also usually have a contemporary backpacker’s

camp. These apple trees are an example of plants indicating an archeological

site.

After I finish my

GPS survey for today I must again

ford the river two times. The rail-bike is very difficult to push across the

submerged and slick river bottom cobbles and I vow to ford this river as few

times as possible.

Fishing Hawk

Logging Camp

Right upstream was the town of Bemis, home to a very large operation,

and big enough to require its own doctor. In Big Doc and Little Doc,

published in 1968, Harry R. Werner, M.D. wrote an account of his days as

a young doctor in Bemis during the first few years of the 20th

century. Here he describes the log camps near Bemis (then called Fishing Hawk):

Fishing Hawk lay in a

narrow valley beside Cheat River. Hills of evergreen rose to a tremendous height on either side. The

logging camps were distributed at six or eight-mile intervals through the

forest. The hills were so steep that the railroad climbed in a series of

switchbacks. That is, the tracks continued for several miles at a grade that was

considered safe, ending in a spur. The log train ran onto the spur, the switch

was thrown, and the train traveled backward on the next frock, proceeding

through several switches, backward and forward, until it reached the top of the

hill.

Two of the camps were

situated on one hill, a part of Cheat

Mountain. Each camp was made up of several buildings and fed and housed twenty

to sixty men. In bark-peeling season, the camps were full. One building

contained the kitchen and dining hall, also sleeping quarters for the cook and

the cookee. In this building the cook was boss. No visitors were allowed in the

kitchen. The cook had a big job and wanted no interruptions, and there was no

room for idlers.

A huge range took up one

side of the kitchen, with room only for the wood box. The opposite side was

flanked by a long pastry table, a sink, and serving table. The walls were

decorated with cooking utensils of all sizes. There were dippers, skimmers,

colanders, long griddles, skillets, and large pans for baking six or eight

loaves of bread. Huge coffeepots that held at least two gallons stood on the

shelves. Barrels of flour, fifty-pound tins of lard, and enormous cans of

granulated and brown sugar stood in rows under the tables.

The cookee prepared

vegetables, washed dishes, and set the long tables covered with brown-checkered

oilcloth. I saw one cookee stand at the end of a table, take one plate at a

time, and with a flip of the wrist spin and place each one where he wanted it to

go. The plates were laid upside down, and a tin cup for coffee was placed on

top. A knife, fork, and spoon were set by the plate.

The men used the backs of

their hands to wipe their mouths, so there was no need for napkins. All the food

was put on the table before the men were called in. Big platters of meat that

was cut in servings; huge dishes piled high with steaming boiled or fried

potatoes, canned corn, cabbage, stewed tomatoes; plates of cookies, doughnuts,

thick slices of bread, and pies cut into quarters, with tall granite pots of

strong coffee and milk served from the cans, loaded the tables.

The men filed in when

called, took their places, and ate. Scarcely a word was spoken during the meal.

In fact, the cook’s orders were, “Eat and get out!” The rule saved both time and

controversy.

When the meal was over,

the cookee gathered up the dishes. He had dishwashing down to a science. The

steel knives, forks, and spoons were put into a cloth bag and submerged into

boiling suds, then dipped into clean boiling water and spread out to dry. The

tin coffee cups were treated in the same manner. The other dishes were then

washed, lifted out onto a rack, scalded, and left to dry.

The bunkhouse was a long

building where the men slept. It also contained a lobby or lounging room where

they spent their leisure hours in spinning yarns or playing checkers. The man

who looked after the bunkhouse was called a lobby-hog. It was his duty to

straighten beds, clean floors, look after the fires, bring in wood, empty ashes,

and clean the brown crockery of the spittoons. He also kept the wood boxes

filled in the kitchen and dining room.

The day began at 6 in the

morning when the lobby-hog yelled, “All out!” There was a scramble as the men

rolled out of their bunks, grabbed trousers and shirts and pulled them on over

long, heavy underwear which they wore day and night. The men washed in tin

basins arranged in a long wooden trough where the lobby-hog had placed pails of

fresh water. Each pail contained a big dipper. One dipper filled a washbasin.

Some of the men used a comb on their hair; others slicked it down merely with

their hands.

Breakfast appeared at

6:30 A.M. The tables were set

with tall stacks of pancakes or buckwheat cakes, stewed prunes known as

logger-berries at camp, fried ham, sausage, beefsteak, potatoes, doughnuts,

coffee, canned milk, sugar, butter, and syrup. The men were through breakfast

and on the job by 7 o’clock. Dinner was served at

12 noon and supper at

6 P.M. In extremely cold

weather, the cookee carried hot coffee and doughnuts to the men at 10 in the

morning and at 4 in the afternoon.

No man who worked at the

Bemis camps could complain of the quantity or quality of the food. Mr. Bemis

never had trouble getting workers. Grievances were talked over with the foreman

and usually ended with an adjustment that was agreeable to all concerned.

Elkins Pail & Lumber, Logging for Porterwood on Lower Shavers Fork

Elkins Pail & Lumber Company, a company active on the lower part of

the watershed, bought up much of the land from Bickles Knob near Elkins to

Little Black Fork, a long tributary about eight miles downstream. But in 1911,

they entered a contract with D.D. Brown under which they sold the land and

received timber at a discounted price indefinitely. Brown then logged it until

about 1917 when, because of labor losses due to young men being “called to their

colors” for World War I, they sold their land to Porterwood Lumber Company,

which was working much of the lower Shavers (D.D. Brown Collection).

Grace Gainer recalls her father logging both for himself and for Porterwood:

Dad cut. He worked there up in the woods, cutting timber. He

cut timber off of our farm, and he took it down to the river. They [Porterwood

Lumber Company] brought their loader up, and it reached across the river, took

those logs over and put them on the train and sawed ‘em, and brought them back

and put them over there for dad to build the barn with.

By 1920, D.D. Brown was at it again on the

other side of the river, establishing a large Frick circular mill with 20,000

feet per day capacity. In 1921 and 1922 the operation had to shut down for a

period because of the depression, but started back again and continued on until

1925 when the Brown outfit moved down to Crystal Springs in Greenbrier County.

Agnes Smith-Wilmoth recalls in a memoir that she wrote about the end of

the logging camps there:

The timber was cut out in 1927, and the railroad was made into a car

road, but years of trains, timber cutting, and the vast amount of logs we’ve

seen will always remain in memory. Trees were cut with crosscut saws. Power saws

not heard of at that time. Saw filers kept the saw sharp. My dad worked on the

railroad. He cut timber and was a teamster for years. Woods work and farming

were his lifework.

There were lumber camps

along the way. Some kept as many as sixty men, and they fed them good. One cook

died in 1922 at the dinner table of a heart attack. That was the camp between

the Squire Long and Columbus Coberly farms called Camp H.

The end of the timber era left the small

community of Pettit, a few miles south of Porterwood, a lonely place and many

out of work. Many residents left for other places, some far away.

Fires,

Floods, and the CCC

All this logging at the same time caused severe ecological damage to

the mountains and erosion along the streams. In 1908, some 10 percent of West

Virginia burned. Many fires occurred because treetops and branches were left on

the mountainsides. These branches dried, creating ideal tinder for fires which

were often ignited by ashes from the steam engines. These fires then spread to

uncut stands, destroying valuable forest land.

Jim White recalls his father battling the fires

during the Depression, at Twin Bridges near Spruce:

So down at the Twin Bridges, I was talking

about this run that come down off Bald Knob. I think the cause of Twin Bridges

is because the run doesn’t come straight down, it bends over to the right side,

which is the Bald Knob side. And as it bends, there are two bridges there to

cross the thing, and out of that, Big Run empties into the river. The Shavers

Fork seems designed to go over and pick up that run and then come back. They

were cutting timber down in that area back then, and it was down there. I

remember my dad going down there and sleeping on the ground, and they were

fighting the fire. For two weeks they were fighting that fire. It was a very sad

time. Now that’s t he only fire that I know about, but there were fires all over

the country. Maybe the state of

West Virginia was burning up because

it was so dry and there was no rain.

he only fire that I know about, but there were fires all over

the country. Maybe the state of

West Virginia was burning up because

it was so dry and there was no rain.

In 1907, a huge flood caused more than $100,000,000 damage along the

Monongahela River—$8 million in the city of Pittsburgh alone—and this is 1907

dollars (Berman 28–30). It did not take long to realize that unregulated logging

was not good for anyone. The fires and the flood, combined with other

environmental disasters taking place around the nation, helped push Congress

into action. In 1911 Congress passed the Weeks Law, and began to purchase land.

They created national forests out of these purchases of private land in the

east. Previously national forests had only been created on public land west of

the Mississippi.

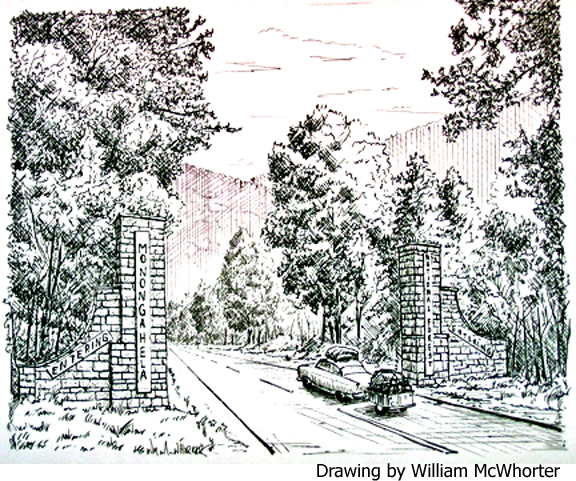

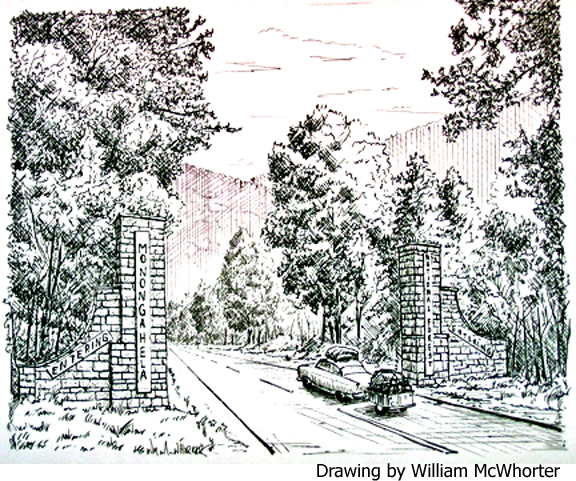

The Monongalia

National Forest was thus

created in 1920 explicitly to protect the headwaters of the Monongahela River,

into which the Cheat River flows. With these lofty ideals, the

Monongahela

National Forest spent much of

its first years simply buying land, planting trees, and battling forest fires.

Very few timber sales happened until the 1940s.

Cross country skiing in the Monongahela

National Forest in the

1930’s.

Photo courtesy Monongahela National Forest.

The National Forest experienced a huge growth

during the Depression as logging companies tried to get rid of their logged-over

land. West Virginia Pulp & Paper Company sold its land from Cheat

Bridge to Bemis to the Monongahela

National Forest during the

Depression, having cut it out and seeing no future value in it.

Because of the severity of the Depression,

President Roosevelt created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a brilliant

idea that took young unemployed men off the streets and gave them lodging and a

small stipend in exchange for public work. It was estimated that 25 percent of

young men were unemployed at that time. The CCC set up camps

throughout the

nation, doing a variety of local development tasks. In West Virginia, many

worked in the National Forests where they planted millions of trees, fought

forest fires, worked to prevent other fires by constructing fire towers. They

built roads and provided watershed improvements. here were two CCC camps that actually stayed on the watershed, although several more were

located nearby and did work on the watershed. The first was

Camp Randolph (F-9), which was

established in summer 1933 and abandoned at the end of

that year, probably due

to the cold weather. This camp developed Stuarts Park, as well as Bickles Knob

tower. This camp was also one of the few integrated CCC camps, having 189 white

and fourteen black enrollees.

that year, probably due

to the cold weather. This camp developed Stuarts Park, as well as Bickles Knob

tower. This camp was also one of the few integrated CCC camps, having 189 white

and fourteen black enrollees.

The other camp also had a short history. Known as Camp Cheat

Mountain (F-23), it opened the summers of 1940 and 1941. Located right off of

Highway 250, it was likely established as a tree planting camp. It was also a

tent camp and never intended for winter use.There were several other camps, like

Camp

Parsons (F-3) and Camp Durbin that also did

quite a bit of work on the watershed but were not stationed there.

Fall in for work detail at Camp Shavers Fork, a CCC camp located near modern day Stuarts Park.

This was one of the first

integrated CCC camps in the state.

September 20, 1933.

Photo Courtesy Monongahela National Forest

Hazel Phillips remembers a bit about the

CCC:

After the train went

out—I don’t know if you ever heard of them or not; they called them the CCC—they

came up there and took out the railroad tracks and ties. They had a camp here in

Parsons, over in the nursery bottom where they spent the night, and they would

bring their meals up in a truck on the other side of the river or in a handcart

probably.

They had a handcart to

travel up and down the railroad track, two men, pumping. And then when they got

through eating their lunch, any of the neighbors along the track, they took

their extra bread and distributed it to the neighbors. And that was a big

treat—store-bought bread. That was during the ‘30s, during the Depression.

But World War II put an end to that service, as the young men were once again

needed to defend their country. It was around this time, due to the Forest

Service’s good management, that the Monongahela National Forest began to enter

logging contracts once again. The first long-term Forest Service contract was

with Mower Lumber Company from 1951 to 1961. This cutting was done on Cheat

Mountain where West Virginia Pulp & Paper had sold its land to the Forest

Service many years before.

Monongahela

National Forest

The purpose of the national forests was enlarged to include timber

wildlife management, and recreation.

Harry Mahoney, a retired Forest Ranger,

explains the Monongahela National Forest’s economic

benefits to the area in a 1989 interview: Aside from the share of timber receipts that go

to schools . . . economic contributions through providing a supply of timber has

traditionally been our major economic contribution to the local area: to have a

dependable supply of timber available on a continuing basis to support a timber

industry in the area. We have been doing that and probably will continue to do

that, at least at a certain level.

The Forest undoubtedly

contributes to tourism potential in the area, contributes that way, both in

terms of providing recreation areas where people can come to, but also in terms

of hunting, fishing opportunities. In a sense, we are also competing with

potential private recreation areas. That has frequently been a complaint. The

government comes in. There used to be free camping, and it wasn’t economical.

Local people developed a commercial campground. We [now] have a charge for most

of our developed camping opportunities.

We also support local agricultural

industries. They are leasing grazing land. That is something: because the

National Forest is here, there is less of a need for some of the public services

that the state or local government would have to provide, in terms of roads and

fire control and all of that sort of thing that we do.

Traditionally—there have been changes in this in

the last ten years—people worked into the ranger’s position. Usually foresters

became rangers and I guess that is still probably usually true. Most

professional employees are foresters, although it is not a prerequisite for the

job. Foresters generally in his earlier steps worked in a variety of jobs having

to do with timber sales, timber stand improvement, reforestation work, national

forest range resource, water projects, recreation resource, whatever happens to

be in the area. Most people get considerable exposure to fire control,

fisheries and wildlife work.

Generally mixed in with that are some

managerial training sessions, personnel management, working with people, public

relations. The last ten years or so there has been more of a trend to selecting

rangers who aren’t necessarily traditional foresters, maybe archaeologists, or

landscape architects, or soil scientists, engineers. They would be coming from

any one of the disciplines that work in a forest.

I was ranger at Parsons during a

considerable portion of the “Monongahela Controversy,” which I presume you are

semi-familiar with. The Forest Service had changed its approach to timber

management in the early 1960s. It had gone from what is called “uneven-aged”

management toward even aged management. Even aged management involves—as a part

of even aged management—regeneration of stands by clear cutting. This means we

would cut all the merchantable trees plus those that aren’t merchantable,

starting with a new stand of seedling. That is one part of even aged management

but that is the most obvious part and most visible part to the public.

The Forest Service has raised the

public on the idea of selection management, cutting individual trees when they

became mature and leaving a general stand of trees up in the woods.

People

didn’t understand why we changed. We hadn’t done a very good of job of

explaining to people why we were changing. That was a prime example of where

people decided we must be doing bad things because we weren’t doing what they

had been taught was good. They did object.

People

didn’t understand why we changed. We hadn’t done a very good of job of

explaining to people why we were changing. That was a prime example of where

people decided we must be doing bad things because we weren’t doing what they

had been taught was good. They did object.

Of course, we undoubtedly made

mistakes in responding to that. This eventually led to a court case where we

were enjoined from making timber sales in which we did other than cut “dead,

large, or mature” trees. This is the wording of an act back in 1897 that

authorized the sale of timber, although practicing selection cutting also

involves cutting trees that aren’t large or mature. So we stopped, for a period

in the mid 1970s, making timber sales.

Eventually this case was appealed.

The appeals court agreed with the local district court here in Elkins and said

that if the law of 1897 was an anachronism, the law should be changed. We would

still have to live by it. That eventually led to the National Forest Management

Act which went far beyond a concern about what kind of trees we cut, directed

all the National Forests in the country to develop Land and Resource Management

Plans and to manage resources in accordance with those plans. This was a very

far-reaching act for which we can take credit or blame or whatever. People

learned to spell Monongahela, I will tell you that much.

Link

to Chapter Four

Logging

is as old as human history. Trees are among the most versatile and abundant

natural resources available, and while Native Americans

undoubtedly engaged in minor logging before the European invasion, they were

limited largely by their lack of metal technology. Stone saws have been found

in West Virginia, but they were crude affairs, certainly not something capable

of cutting down a 300-year old oak tree.

Logging

is as old as human history. Trees are among the most versatile and abundant

natural resources available, and while Native Americans

undoubtedly engaged in minor logging before the European invasion, they were

limited largely by their lack of metal technology. Stone saws have been found

in West Virginia, but they were crude affairs, certainly not something capable

of cutting down a 300-year old oak tree.

a twist in his suspenders for each day he

worked, so he knew he was getting paid fairly. Some of the evidence from those

little hamlets comes from the news reports that some of the camps sent into the

Pocahontas Times to report on life in the camps. Full of wit and

at times difficult to understand, these letters from the camps offer insight in

the positive attitude held by the wood hicks. Keep in mind that the first

article was written July 4, 1901:

a twist in his suspenders for each day he

worked, so he knew he was getting paid fairly. Some of the evidence from those

little hamlets comes from the news reports that some of the camps sent into the

Pocahontas Times to report on life in the camps. Full of wit and

at times difficult to understand, these letters from the camps offer insight in

the positive attitude held by the wood hicks. Keep in mind that the first

article was written July 4, 1901:

Canadian picked up a poker and made for the cook, who took a

butcher knife from under his apron and told the big Canadian to come on in but

he would leave his head in his hat in the lobby. The camp boss, Lanty Cole,

separated them, but there was no more eating at the table with hats on.

Canadian picked up a poker and made for the cook, who took a

butcher knife from under his apron and told the big Canadian to come on in but

he would leave his head in his hat in the lobby. The camp boss, Lanty Cole,

separated them, but there was no more eating at the table with hats on.  disappeared. Devane Cussins shares

memories from when he was a child visiting the log camps a little later, around

the 1940s:

disappeared. Devane Cussins shares

memories from when he was a child visiting the log camps a little later, around

the 1940s: metal was heated. Or I could turn the crank to the grindstone while

one of the loggers sharpened his axe.

metal was heated. Or I could turn the crank to the grindstone while

one of the loggers sharpened his axe. logging. The last horse camp (Camp #95) pulled up camp on

logging. The last horse camp (Camp #95) pulled up camp on

Increases in technology had a great impact on

profits. Unfortunately, this also had an increased effect on the landscape, as

much of the new technology focused solely on how to increase board feet removed

per day and not on how to sustain the forest. Luckily for Cheat Mountain, West

Virginia Pulp & Paper had some forward thinking individuals at the time. Early

on they planted 25,000 spruce trees just off Shavers Fork in 1909 and 170,000

spruce and 2,000 yellow poplar in 1910 (PVB Collection).

Increases in technology had a great impact on

profits. Unfortunately, this also had an increased effect on the landscape, as

much of the new technology focused solely on how to increase board feet removed

per day and not on how to sustain the forest. Luckily for Cheat Mountain, West

Virginia Pulp & Paper had some forward thinking individuals at the time. Early

on they planted 25,000 spruce trees just off Shavers Fork in 1909 and 170,000

spruce and 2,000 yellow poplar in 1910 (PVB Collection).

he only fire that I know about, but there were fires all over

the country. Maybe the state of

he only fire that I know about, but there were fires all over

the country. Maybe the state of  that year, probably due

to the cold weather. This camp developed Stuarts Park, as well as Bickles Knob

tower. This camp was also one of the few integrated CCC camps, having 189 white

and fourteen black enrollees.

that year, probably due

to the cold weather. This camp developed Stuarts Park, as well as Bickles Knob

tower. This camp was also one of the few integrated CCC camps, having 189 white

and fourteen black enrollees.  People

didn’t understand why we changed. We hadn’t done a very good of job of

explaining to people why we were changing. That was a prime example of where

people decided we must be doing bad things because we weren’t doing what they

had been taught was good. They did object.

People

didn’t understand why we changed. We hadn’t done a very good of job of

explaining to people why we were changing. That was a prime example of where

people decided we must be doing bad things because we weren’t doing what they

had been taught was good. They did object.