Chapter Four

“The snow was so deep that we pushed

the windows back, reached out,

and could make snowballs. That’s no

exaggeration.”

— Pat

Dugan, Spruce machinist

Spruce: - Ghost Town

Spruce,

West Virginia (elevation 3,853). - The town of Spruce, located high in the

wilds of Cheat Mountain, is thoroughly intertwined with West Virginia’s

industrialization. In many ways, the town typifies industrial history in the

state. Born during the logging boom, Spruce transitioned into a coal town and

now exists as a tourist destination.

Spruce,

West Virginia (elevation 3,853). - The town of Spruce, located high in the

wilds of Cheat Mountain, is thoroughly intertwined with West Virginia’s

industrialization. In many ways, the town typifies industrial history in the

state. Born during the logging boom, Spruce transitioned into a coal town and

now exists as a tourist destination.

Stories that emerge

from Spruce are mostly about people breaking rules and instituting

self-governance in a place that corporations created, owned, ran and destroyed.

The people, who lived in this high, cold town, continue to feel a bond with each

other, even though their time there is now more than fifty years distant.

Mill Years, 1902–1926

The story of Spruce

begins back in Scotland with the Luke family. There William Luke learned the

process of papermaking; he primarily used old house rags. In 1852, he immigrated

to the United States and soon realized that rags were not a good source for

commercial paper production. Using a process derived from the rag method,

William created a way to make paper from wood pulp (Clarkson II, 25).

William

Luke’s son was the one who truly created the pulpwood empire: John Luke

established the West Virginia Pulp & Paper Company, which was to become one of

the largest paper companies in the country during the 1910s and ‘20s. The

company quickly grew, building mills in Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia

and Virginia.

West Virginia

Pulp & Paper bought Covington, Virginia, the site of one of these pulp mills, as

well as much of the southern part of Cheat Mountain for its virgin timber to

supply the mill. The price paid: $8.65 an acre, a pricey sum in those days! This

land had belonged to James H. Dewing, who started buying up the land in the

1880s in order to profit from West Virginia’s timber future (Deike, 4).

Red Spruce Paper

Red spruce in the

area made some of the best paper—the softwood had the right grain and

consistency for making excellent pulp. Soon the company shipped paper by rail to

Covington. Italian and Austrian immigrants, some fresh off the boat, built many

of the railroads in from Cass and Bowden, to Bemis and up to Spruce. However,

problems soon arose.

Red spruce in the

area made some of the best paper—the softwood had the right grain and

consistency for making excellent pulp. Soon the company shipped paper by rail to

Covington. Italian and Austrian immigrants, some fresh off the boat, built many

of the railroads in from Cass and Bowden, to Bemis and up to Spruce. However,

problems soon arose.

The log camps

employed men six days a week. On Sundays, especially the Sundays after payday,

many men went to Cass and got drunk, so drunk that Monday’s production was

notably lower, as many men were still nursing hangovers. The situation was also

unsatisfactory for the married men who wanted to spend more time than one day a

week with their families.

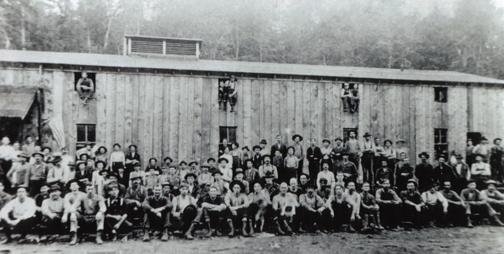

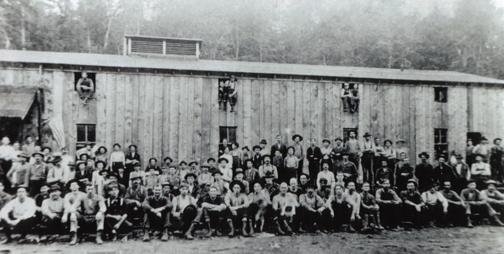

Logcamp: the huge log-camp that later was the site for the town of Spruce.

Note the men hanging out of the second story windows. Photo courtesy Roy

Clarkson

Finally, and perhaps the most compelling for West Virginia

Pulp & Paper Company, was a problem at the Covington Mill. Originally the

Covington mill did all the debarking. Unfortunately, the bark, which was burned

to fuel the mill, created a feathery ash that sometimes floated into the

windows, ruining entire rolls of paper. For a while they tried spudding the

logs—manually removing the bark from the tree when it fell—but sand often got

rubbed into the wood on its way to the train, again ruining the paper.

Company Builds

Town

In order to

solve these problems, someone put forth the idea of a town on top of Cheat

Mountain where the company could control virtually all commerce going into and

out of the town. They could build a debarking (also known as rossing) mill and

provide a place for the men with families to live. This town was named Spruce,

after the abundant spruce trees in the area then being harvested.

The

Pocahontas Times published an excellent introduction to the then brand new

town:

Spruce is a camp chopped out of the forest on

Cheat Mountain in Pocahontas County—back up the mountain from Cass and reached

by a switchback railway that lumber trains must ascend, climbing a grade of from

250 to 450 feet per mile. The town’s location is probably the highest in the

south having an elevation of 4,000 feet above sea level and a climate that

brings frost every month during the year.

I visited it in the mild days of early

November, yet it was dead of winter there. As our cogwheel engine climbed the

heavy grade, we could note the vegetation changes as the train reached higher

levels. Bye and bye we were amid snow flurries and cold winds and finally as the

train straightened itself out on the elevated plateau valley we looked forth

upon a scene where winter reigned supreme—snow, ice, and frozen streams. The

snows that fell there in November usually remain till April and sometimes later,

but the hearty lumbermen do not mind and the energetic company that employs

them, push right along at all seasons and in all weather. They have built on

that plateau a network of railway lines and have established at its principal

junction point the town of Spruce, where (there) is a big barking mill that

supplies the great paper mills at Covington, Virginia.

The place is not eighteen months old, yet it

has its comfortable hotel, its store, its electric lights, its snug offices, it

boardwalks and its long rows of workmen’s’ houses. The plant employs 480 men,

mostly Austrians, and in the spring 1,000 more of the same are to be added to

the force. Superintendent Jones has a big proposition and manages it

skillfully. He is a Virginian from Covington and is assisted ably by another

Virginian Mr. C. Z. Sellers of Rockingham county, and but recently, ticket agent

for C. W. Railway at Stokesville.

Mr. Jones seems to prefer Austrian labor for

the reason that it is hearty, cheerful and contented. The great force of them he

will soon have are to be engaged in culling the smaller timber from the area

left by the woodsmen of Spruce Lumber Company of Cass. All small trees and

saplings down to four inches diameter are felled and barked at the peeler mills.

Sixteen carloads of this product are now sent down the mountain daily. What can

and will be gotten out when the 1,000 reinforcements comes in the springtime can

only be conjectured.

The product of this mill in its entirety

together with the vast quantity of other timber gotten out on Cheat Mountain

must all come to Cass on the C&O for shipment. Here are located the great

sawmills of the West Virginia, Spruce Lumber Company, that have in recent years

built up and incorporated a live business town. Its outgoing freight receipts, I

am told, often exceed $20,000 per month.

The mayor (for the town has a

mayor) is Mr. J. A. Kirkpatrick, and here again we see that West Virginia in her

development has drawn the on the Old Dominion for some of its best men, for Mr.

Kirkpatrick is a Virginian and a native of Rockbridge county. He is also

proprietor of the company’s large hotel, where the traveler will find the

comforts of life, to say nothing of its luxuries when at night he turns on the

electric light in his well-heated bedroom. Nowhere will the traveler find a more

obliging or considerate host than he (Pocahontas Times, February 2,

1905).

Population

Waxes, Wanes

Visiting Spruce

today, it is hard to imagine a large mill in the middle of the forest except for

the ruins that bear silent witness. At one time that mill was a huge production

point. According to Roy Clarkson, the mill initially cost $50,000 (in 1905). The

town of Spruce’s initial population was approximately fifty people.

Polk’s

directory named the following positions:

E.P. Shaffer—postmaster;

E. Cruikshank—train dispatcher;

O.G. English—express and

telephone agent;

J.L. Ervin—shoemaker;

Amos Lyons—blacksmith;

Robert Newcomer—proprietor of

Hotel Spruce and Pocahontas Supply Company;

L.B. Smith—blacksmith;

O.B. Sprague—blacksmith; and

D.J. Taber—lumber superintendent.

By 1906, the

population had jumped from fifty to 300. The mill, which opened up in February

1905, operated two shifts a day until it shut down in 1925. That’s what brought

people to the town. Here is how it worked: smaller trees not harvested in the

initial logging—usually anywhere from four to fifteen inches in diameter—were

selected in this second cut. Trees were brought to the millpond, which was steam

heated in the winter to keep it from freezing. The logs soaked in the pond,

which helped loosen the bark before they were transported up to the mill via a

series of cleats on a bull chain. Once in the mill, trees were cut into

twenty-four-inch chunks and then taken to the rossing machines. Richard Sparks, a Spruce expert explains,

“I believe this picture must

be from 1926 because my interpretation is the rossing machinery is being removed

from the mill. This is the southwest corner of the building; a section of the

front wall has been cut away. The log car you can see is on the pond track and

they are probably using a cable hooked to a locomotive or a log loader to move

the machines. The large concrete tubs that you can see at Spruce today were the

foundations of this machinery. Note there is only one smokestack where there had

been three.”

Courtesy Richard Sparks

Spruce Rossing

Mill

Each of the

eighteen rossing machines required seven men (126 men per shift) to operate. The

machines’ curved knives, mounted on heavy metal wheels, quickly removed the

bark, and the wood was then ready to be shipped to Covington. In order to

prevent the steam train ash from getting on the pulpwood, West Virginia Pulp &

Paper began shipping wood in closed boxcars. Workers filled approximately twelve

to sixteen carloads everyday, each carload holding anywhere from ten to fifteen

cords of wood. Operating six days a week, this meant that an estimated 138,240

cubic feet of pulpwood left Spruce each year. The leftover bark was then burned

in Spruce and used to heat the pond and the 400 horsepower steam generator,

which provided electricity for the mill as well as some of the houses and the

hotel in Spruce (Clarkson I, 123).

The mill ran until

1925. In this first era, Spruce housed approximately 350 people, quite a number

considering the fact that the only way to get to the town was by rail or by

foot. As much as WVP&P wanted things to revolve around the mill, they did not.

Many of the stories generated during this project happened during those years.

Pack Dogs and

Butter

Harvey

Hamrick relates a few early stories about Spruce. He was a child in the early

1920s and lived five or six miles away (by rail) in Mace. Harvey occasionally

went into the little town of Spruce to sell produce; it was a difficult place to

try to raise crops due to its cold climate and frequent frosts.

He relates:

Oh, we took corn on the

cob and beans. Tomatoes were too heavy. We sometimes took chickens. I guess

that’s about it. Each one of us had a dog; they’d have to carry this stuff. We’d

just put it on their back and they would carry it all the way up that track.

Well, that was the only way to get in was on this railroad.

Sometimes we would get

to ride Shays in there, old Shay engines, but not very often. Sometimes we got

to ride back out. One of the engineers was Cal Bradley, and he run the old

Number 12 Engine, the biggest Shay that was ever built. He was real nice to us.

Some of the others wouldn’t slow down, and we would have to jump off while it

was going.

I’ll tell you a little incident

that happened: it was very rarely we took any butter or anything that like

because it was hard to get over there, you know, in good shape. It was kind of

cool that day so I told Mom I would take, I believe, four or five pounds of

butter. And she packed it in a bucket for me, and I had something else, I don’t

remember what. But I went by myself that day, and I got to ride the train.

I waited till afternoon.

If you waited till afternoon the log train went up, and you could ride it, which

would save you four miles walk on that railroad. Anyway, this day I was riding

on the caboose, and they didn’t stop. I wanted to get off where the blacks

lived. And

this guy on there he says, “You get off and run along the side, and

I’ll hand you the butter. ”

”

So he

did, and I got off. I did fall almost. It was going pretty fast. It was just

before the cross, a good little ways before we

crossed the river and before we

come into the other line that goes to Cass. And I fell partly, but I got up and

run along side, and he handed me the butter. I missed it, and it hit the side

and come out and got cinders all over it so I about cried over or did cry over

it. Then I went down to the millpond and tried to wash that butter off. (Laughs)

You might know I didn’t sell any of it although I tried. Some of them laughed at

it. I don’t blame them for not buying it.

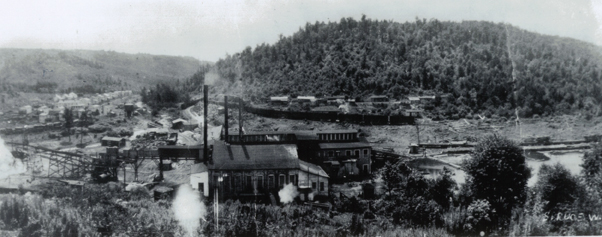

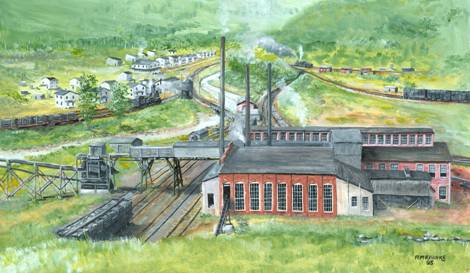

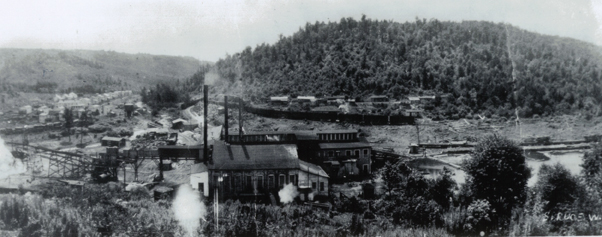

The town of Spruce taken by Ivan Clarkson in 1920.

This is perhaps one of the earliest and best photos of the whole town.

Photo courtesy of Roy Clarkson

-

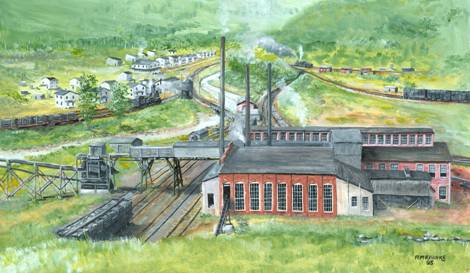

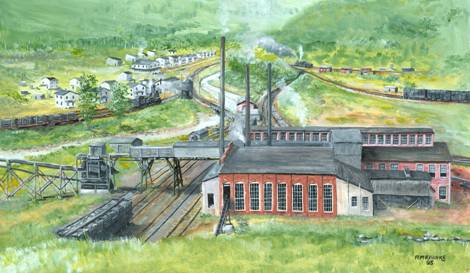

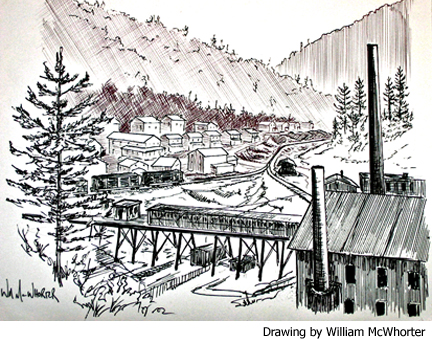

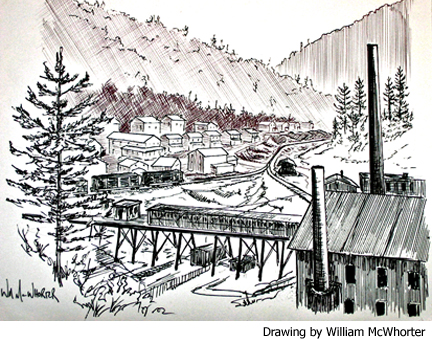

A

painting of the Spruce mill and town around 1923 by Richard Sparks, he notes,

“The poured concrete structures were added to both ends of the powerhouse in the

early 1920’s. Years later they would be among the last standing ruins at

Spruce. In the last modifications to the mill, a third smokestack was

added and a fourth track was laid in the mill yard. The trestle of the

endless chain conveyor which exited the second story of the mill and ended at

the waste pile on the bank of Shavers Fork was modified to include what appears

to be a chute in the center for loading the pulpwood cars. Also a small

trestle was built from a switchback track on hillside to the north of the mill.

This structure crossed the millpond spillway and went into a window opening.

As this was right above the location of the fireboxes, it possibly was a system

for “automating” the coal supply.”

Courtesy Richard Sparks.

Railroad Years 1928–1951

As the woods around

Spruce thinned out so did the need for labor at the mill. In 1925 West Virginia

Pulp & Paper shut down the Spruce mill permanently, and almost all of the

inhabitants of Spruce left. A smaller debarking mill was constructed at Cass,

which served the same function as the one in Spruce. However, that same year,

the second life of Spruce was being conceived.

Coal had been

found in the mountains of Randolph County, and Western Maryland, a railroad

company, decided to buy the stretch of rail line from Bemis to Slaty Fork.

Spruce found a second life with the buyout, and soon a new group of people

joined the several families that remained after West Virginia Pulp & Paper

Company abandoned the town. Spruce was now a railroad terminus and perhaps one

of the most unique stations in the east.

H.A. McBride

writes:

In

dealing with the Elkins district, mention should be given to one of the

strangest of all railroad stations. It is at Spruce, West Virginia, on the

Webster Springs “freight only” branch. Here on a mountaintop, 4,000-feet high,

is a unique engine terminus. There are no highways to Spruce, and the only way

to get there is on foot, horseback or on the railroad. In winter, with heavy

snows, even these means fail, and the town is sometimes completely isolated for

days. Some sixty employees of the WM [West Maryland] live here with their

families in houses provided by the company. There is a company schoolhouse and

a teacher for Spruce’s children, and a rail car to bring in a doctor if one is

needed. The railroad, until recently, has maintained small engine shops and

yards, with coal, water and sanding facilities

Fortunately, some

people who lived in Spruce during this second era are still around to tell

stories about the old ghost town. Many of the people who lived there only spent

their childhoods in Spruce, but what a childhood it must have been.

Bare Feet in May

Wanda Sharp

shares a few stories of her childhood in Spruce:

We always went bare

footed the first day of May regardless. I never wore my shoes again until fall.

We always went swimming the first day of June, and man was that water cold. We

had a swimming hole under the Shay bridge, and you learned to swim early. The

older boys stood in a circle in the water and had me to jump off the bridge.

They knew I couldn’t swim but swore they wouldn’t let me drown.

I jumped. They all swam

away and started yelling for me to kick my feet and hands, so I learned to dog

paddle in a hurry. We played in the water a lot. We had a raft made out of

crossties that floated on the water. The pond would always freeze over in the

winter, and we’d ice skate or sled ride on it.

Down below the pond was

a little island you had to wade across the river to get to. The boys and us

girls built a playground out there. We had a merry-go-round, rope swings from

the trees, a seesaw and benches and a picnic table. Sometimes we’d have wieners

or marshmallows to roast over there. We were real proud of it because we’d done

the work by ourselves.

We had to keep ourselves occupied.

We made our own stilts out of poles—we could all walk on them. We made our own

dollhouses out of pasteboard boxes. Dad would brace the corners and the roof for

us with slats of wood. Mother gave us scraps of linoleums for our floors and

material for our curtains and bedclothes. We’d use our imagination using

matchboxes and whatever else we could find to make our furniture. Some of them

were really nice.

We used the Sears

Roebuck catalog for more then just toilet paper too—we’d cut all of our paper

dolls and their clothes out of it and play for hours with them. We got magazines

called Look. The first kids had to start a story using the first

picture—they’d stop in mid-sentence and pass it to the next kid—they would have

to continue the story using the next picture in the book. We always had fun with

that game.

Spruce School,

Craw Crabs, and Tadpoles

Leo Weese,

who also grew up in Spruce, talks about school:

About every teacher they got in there—they couldn’t take the pressure—they had

to leave. I’ll tell ya, I was a little mean, mischievous. My mom would tie me up

to the clothesline, you know, just like a dog. ‘Cause them guys at the track

crew used to tell my dad that I was up there throwing rocks at them.

Well, I learned to untie

myself. I’d run up there and barrel the rocks at them, then run back down and

tie myself back up. And they’d tell Dad. Mom would say, “No, it wasn’t him. He

was tied up to the clothesline.” So it went on like that, and they weren’t the

only ones I’d throw rocks at.

Then one time I was working in the

mines, and I was telling them guys about me throwing rocks at them loggers. And

this one old man, Bay Tenny, he pointed his finger at me, “You’re the little

son-of-a-bitch who was throwing rocks at me.” Here he was working on one of them

log crews. He said, “Yeah I was wondering who that little guy was.” He was

working for Mower Lumber Company, working up at those log camps.

Wanda Sharp

recalls the roughness of school in Spruce also:

The women schoolteachers

always boarded with us. One weekend Mother and Dad went out, and the

schoolteacher was babysitting us. There was this one family that had it in for

the school teacher. I guess she had whipped one of their kids. As soon as Mother

and Dad left, they came up to our house and drug the teacher out into the yard

to fight with her.

The women schoolteachers

always boarded with us. One weekend Mother and Dad went out, and the

schoolteacher was babysitting us. There was this one family that had it in for

the school teacher. I guess she had whipped one of their kids. As soon as Mother

and Dad left, they came up to our house and drug the teacher out into the yard

to fight with her.

We started screaming for Pappy Cussins to help

us. He ran over, jumped our fence, and hit the man at least three times before

his feet ever touched the ground. Several of the other railroaders came up. They

all stayed close by until Mother and Dad came home. After that, the kids came to

our house every morning and walked the teacher to school, even the older boys

that were already out of school walked with us. They continued to do this until

school was out for the summer.

Spruce school picture. From left to right: Front

row: Okareta Powers, Millie Calain, Mildred Teter, Glenda Ketterman. Second

row: Anita Fay Fansler, Hershal Broughton, Booch Cussins, Elmer Semones, Arveda

Powers, Jack Ketterman, Bob Semones. Back row: Christine P, Ruth Semones, Alice

Sharp, Juanita Waugh, Jo Ann Semones, Darlene Calain, Joe Ketterman, Betty

Broughton, Eddie Broughton and Odbert Calain. Taken 1945. Courtesy Dorie

Powers

The last

teacher to teach in Spruce was Mr. Bell. We all liked him, but he just didn’t

have any control over us so we made his life miserable. If he had ever told our

parents some of the things we done we’d all be dead. But he never told on us.

We’d upset the outhouse then tell him if he didn’t take us on a hike to the fire

tower we weren’t going to set it back up. He’d always give in and take us.

Sometimes we’d climb up in the tower and not come down, he was afraid to climb

up after us.

One time we had him up at the top

of Cass hill. One track went to Cass; one went to Spruce; one went to Bald Knob

and one down to an old logging camp. We pretended like we didn’t know which

track went to Spruce. The Shay train came up from Cass headed down to the old

logging camp. We told him to run and catch the train and find out which track

went to Spruce. I can still see him running after that Shay train waving his

arms and hollering. As soon as he went around the turn out of sight, we took off

for Spruce and left him up there. I was out on our front porch that evening

about 6 p.m. when he came limping down the track. He must have rubbed a blister

on his foot. I giggled as he went by, but he didn’t say anything.

He kept a bell on his desk at

school, and he’d ring it at recess time. Sometimes Pauline and I would go up and

ask if we could ring the bell. He thought we meant when it was time to ring it.

He’d always say yes, and we’d grab it and ring it. All the kids would jump up

and take off. We pulled that on him at least once a week. We had a stone crock

water cooler with a little spigot on it to hold our drinking water at school.

Every morning one of the kids would take a gallon bucket of water to put in the

cooler.

One morning Pauline and I went to

get water. On our way back to school we got some craw crabs, lizards, tadpoles,

and frog eggs and put them in the bucket. We brought them back to school and put

them in the water cooler. We told the kids not to drink the water, but we’d all

snicker every time Mr. Bell got up to get a drink.

One morning Pauline and I went to

get water. On our way back to school we got some craw crabs, lizards, tadpoles,

and frog eggs and put them in the bucket. We brought them back to school and put

them in the water cooler. We told the kids not to drink the water, but we’d all

snicker every time Mr. Bell got up to get a drink.

One time Pauline and I

went to school early and filled the wash pan full of craw crabs and lizards. We

put them in Mr. Bell’s desk drawer, they crawled out during class, and everyone

got a big laugh out of that.

Once we were teasing him about one

of the older girls who was already out of school. We were telling him she liked

him and that he should write her a love letter and have her meet him somewhere

that evening. He went along with the teasing. We told him what to write and he

wrote it. I asked him if I could deliver the letter to her. He said yes, but he

took me aside and told me to just go out and tear the letter up. He wanted me to

pretend to give it to her. Well, you guessed it; he picked the wrong kid to

trust. I took it down and gave it to her mother. Her mother came up to the

school and cussed him until a fly wouldn’t lie on him. The devil must have made

me do it. He never even got mad at me.

Once I asked him why Easter didn’t

come on the same day every year like Christmas did. He said he didn’t know why,

but a few years later—he had joined the Army—I got a letter from him explaining

why Easter didn’t come on the same day every year.

One of the parents came up to

school and jumped on him over whipping their kids. The man hit him with his

railroad hat; he was so scared he wet his pants. He quit teaching in the middle

of the school year. I can’t say that I blame him. He was a nice person but just

too easy on us kids. We never pulled that stuff on any other teachers.

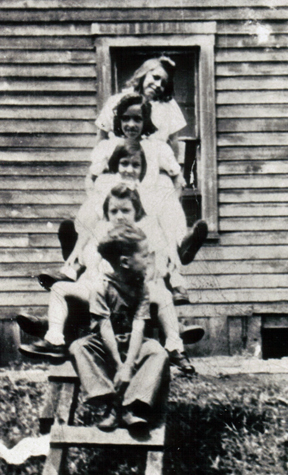

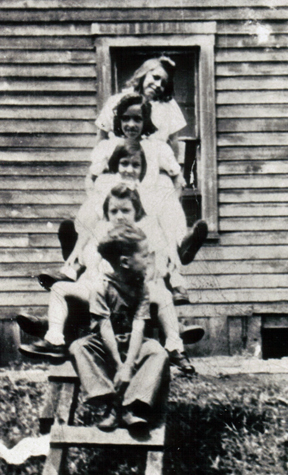

Spruce

kids: The X at the top of the photograph shows how high the snow had drifted

the winter before. Pictured here, top to bottom is, Arveda Powers, Glenda

Ketterman, Okie Powers, Wanda Powers, and Jimmy Ketterman. Taken 1943.

Courtesy Dorie Powers

Bible Verses and

Smoking on the Skid Landing

Wanda Sharp

continues:

The boys were always

good about sharing their sleds and bicycles with us girls, but we had one boy

who would never share. He got a new Red Flyer sled for Christmas. Me and Pauline

wanted him to let us try it out, but he wouldn’t do it. So the other three boys

took his sled away from him and let me and Pauline use it. He said he was going

home and tell his

Dad on us, so the boys held him down in the snow and told us

to ride over his fingers. We did, and then the boys dared him to go tell on us.

He got a new bike one time, and I guess the other boys were jealous; anyway they

roughed him up a bit. His Dad got on them the first chance he got and asked

them, “Why’d you jump on Harry fur?” So from then on we called him Harry Fur. We

all liked him but loved to tease him.

on us.

He got a new bike one time, and I guess the other boys were jealous; anyway they

roughed him up a bit. His Dad got on them the first chance he got and asked

them, “Why’d you jump on Harry fur?” So from then on we called him Harry Fur. We

all liked him but loved to tease him.

We hardly ever had meat on the

table. Once in a great while Mother would kill a chicken. If we had meat, it was

wild meat, such as deer, squirrel, turkey, groundhog and coon. Dad liked coon

but I could never get past the smell. One time Dad and another man went to get

fish. They took a quart jar and put carbide in it and put little pinholes in the

lid. They’d tie a rock to it and throw it in the water; when the water got to

the carbide it would blow up and kill the fish—they all floated to the top of

the water. They must have had a washtub full of fish. I remember cleaning fish

until I was sick. I don’t like fish yet today.

Boardwalk: Two children and their dog in Spruce, note the board walk behind

them.

There were no roads in Spruce, as there weren’t any roads leading to and

from the town.

Photo courtesy Leo Weese

Dad always

raised hogs so we had hog meat in the wintertime. Once Pauline and I went up to

the hog pens, and we decided to play cowboy and use the pigs for our horses.

Inside the pen was a little house with straw in it and a little door just big

enough for the pigs to get through. Pauline dared me to ride one first, so I

jumped on that old pig’s back and grabbed its ears. It took off running to the

little house, the pig went in, and I went off. I landed in the mud and hog

manure. Pauline set on the fence and laughed at me. There’s nothing funny about

your best friend sitting on the fence laughing and holding her nose telling you

that you smelled like hog poop. That was the end of my cowboy days.

You may not believe the

next two stories, but they are true. We had always heard it said there was a

verse in the Bible that would stop someone from bleeding to death. Once Mother

and Dad were gone, and Mildred and Pauline were spending the weekend with us. We

were outside playing, and Mildred jumped off the roof of the playhouse onto a

broken jar. She cut her foot really bad. We were so scared we didn’t know what

to do—blood was shooting out all over the place. She told my sister Okie to run

up to the house and get the Bible. She did, and we didn’t know which verse to

read so we just opened it and read the first verse we came to. Mildred’s foot

quit bleeding right away. We poured it full of turpentine and wrapped it with a

rag, and it healed up in no time.

Another time all four of us girls

went up on the old skid landing smoking cigarettes we’d got somewhere. Okie was

trying to get her cigarette lit and singed all her eyebrows and lashes off. Her

hair was real black so it stood out like a sore thumb. We knew we were in deep

trouble so we built a cross and got down and prayed for God to make her brows

and lashes like new. When we finished praying you couldn’t even tell they’d ever

been burnt off. The Bible says we must have the faith like a little child.

Virgil

Broughton was a child with this bunch but remembers a friendlier Spruce:

The biggest thrill we’d

have in the wintertime was we’d go upstairs and jump out the window into the

snow, ‘cause it would get four, five, six feet deep. We’d go out and ice skate

on the river. The winters aren’t like what they used to be. With a sled, you get

a running start on a sled, and you could go for a mile. There was an island. The

railroaders built a merry-go-round for the kids—set a big timber in the ground,

a big board over it—and that thing would go around.

And the sand

house—people don’t know what a sand house is—it’s full of sand, real warm sand.

They kept it heated with pipes running through it. They used sand in the engines

because if you’re pulling 150 loads of coal, those wheels will spin just like a

tire. There’s a big sand box in those engines, and they’d just pull a lever and

the sand would spray out on the rail. It was just like putting chains on your

car. We’d go over in the wintertime, and we’d play in the sand pile. It was just

like playing in a summer hayloft. They heated it so it wouldn’t freeze.

Lee Sharp’s

Famous Bear Cubs

Many people

spoke of the famous Spruce bears. Devane Cussins, also a child at that time,

remembers:

I

can’t remember how old I was, maybe around five or six years old—it was the

early or mid 1940s. My father and Lee Sharp had taken a motor car and gone

fishing somewhere between Spruce and Cheat Bridge where there was a railroad

siding so they could park the motorcar [which ran on the train rails]. They was

fishing the Shavers Fork of Cheat River.

Along in the evening my

father was headed back to the motorcar when he heard a noise and found that a

mother bear had just sent her three small cubs up a small tree and disappeared

into the under brush. After seeing the small cubs in the tree, he started

yelling for Lee Sharp. When Lee Sharp arrived they decided that Lee would go up

and get the bears while my father stayed on the ground to watch for the mama

bear—knowing that if the cubs made a noise, she would be back.

Sure enough, while Lee

was getting the cubs, they started to make a noise, and here came the mama bear.

My father said he broke a good size tree limb off a tree and began yelling and

screaming like he was crazy and began beating the tree branch on the ground.

Amidst all the noise, the mama bear took off and disappeared. They got the bear

cubs, jumped on the motorcar and returned to Spruce, where they made a cage out

of wooden poles. Lee Sharp with one of

the Spruce Bears as it was growing up. The bears developed a strong bond with

Lee. Photo courtesy Wanda (Powers) Sharp

One Sunday my father brought one

of the cubs to our back yard to play. We had two dachshund dogs—they slept

behind the stove in the kitchen. We had a screen door on the back porch that led

to the kitchen, and when the black dog and the bear got playful, the bear got

after the dog. And the dog headed for the kitchen, but he didn’t stop for the

screen door, he went right on through the screen. The bear slid across the porch

to the door and stopped.

Another time, in the

summer when the blackberries were ripe, Lee Sharp, myself, and a couple of other

kids, had taken one of the bears to pick blackberries. By this time the bears

was getting pretty good size. About three or four feet tall when standing on

it’s hind legs. Everyone would pick berries and the bear would go to each person

and eat the berries from your hand. After feeding the bear two or three

handfuls, I decided to trick the bear. So when he came to me, I held my hand

closed. He became very angry when I would not open my hand, and I still have a

nice scar on my wrist where he decided to take a bite of my arm.

I don’t

remember what happened to all three, but I do recall that some man had come to

get one to take to his home, which was away from Spruce. He had locked the bear

in the trunk of his car and while driving down the road, the bear decided he

wanted out and was coming through the backseat when the man had to shoot it.

Bert Weese,

Leo’s father recalls them as well:

Cussins and Sharp caught

two cubs, and they built a pen for her, and Sharp’d get in there and play with

her. He’d get in there, and that bear lunged, jumped, and grabbed him. It opened

its mouth and put it on his leg. Wouldn’t bite.

I said, “You better be

careful.”

One night John and I came in and

saw a groundhog go in a hole. When we did the switching and put the engines

away, we went over and dug the thing out and brung it over to the pen, opened

the door to the lock, put it in.

John said, “That’s the

cruelest thing I’ve ever seen. I’ll never do that again.”

That bear just moved

over, set one foot on the groundhog, got a hold of it with his mouth and tore

him in half. Lee sold him (the bear) to a couple fellows. They come up to Mount

Airy and parked their car. They had one of those little turtlebacks.

They left the car at

Mount Airy and came in and got the bear. They just got halfway around that

circle—the bear sat down—he wasn’t going to go. So Lee had to go over there and

loosen the chain, and away they went to Mount Airy. They put him in that

turtleback thing, in the trunk of the car. As they were going down the road,

they were bumping around, and the bear was going to come through where they was

at. He was tearing the place up. They finally had to shoot him.

Sixty Brook

Trout

People in

Spruce enjoyed other pastimes too. Hunting and fishing were common activities.

Tom

Broughton, an engineer, recounts:

Tom

Broughton, an engineer, recounts:

I saw Gordon and he

said, “Do you want to go up river?”

I said, “Yeah.”

He had fish worms, and

the river was closed to fishing. They had that river from Spruce up to raise the

trout in, and we went up there.

He said, “I’m going to

cut a pole here and see if we can’t catch a few fish.”

So he did. He had the

hook and line in his pocket, the fish bait, and he said, “Now you watch, and

I’ll catch us a mess of fish.”

He caught sixty brook

trout—six-seven-eight inches. One time, this is kind of hard to believe, but

there were so many in there, they all run to that worm and the line hooked one

to the other one in the gills. He throwed it out on the bank with the one that

was on the hook and caught two with one hook with just the line hooked into the

gills.

Leo’s catch. Courtesy Leo Weese.

Murder

in Spruce

A murder took place

up on the mountain during Spruce’s second era. This tale has different versions.

The people who were kids at the time apparently heard a different story than the

adults.

Leo Weese,

who was a child at the time, related this version:

I’ll tell you a good

story that happened up there. They had a big dugout, that’s what they called it,

but what it was a dispatcher shanty down there. And this guy was fooling around

with this other guy’s wife. This Gainer boy was fooling around with Teeter’s

wife. And Gainer was sitting in the dugout, and in come Teeter with a shotgun,

12-gauge. Said, “I’m gonna kill you.”

Gainer said, “No you

ain’t Teeter.” He started up out of the chair, and he blew him in half. Boom!

That happened up there. I think Teeter got five years or something. Should have

gotten nothing.

Virgil

Broughton, also a kid at the time, recalls a similar story:

They had a phone

booth—they was three of them—oh, I’ve slept in them . . . They leak now, but we

used to stay in them for a week or two at a time in the ‘60s and ‘70s, hunting.

And there was another one up at the Cut. But there was a great big one in

Spruce; they called it the Caller’s Office. And boy, you talk about the moon

shining and poker playing over the weekend . . . Yeah, the punch cards, the

gambling. There wasn’t nothing else for them to do.

I heard of a guy getting

killed in there one night. One of the guys walked in there with a double barrel

shotgun and blew a guy’s head clear off. Turns out he was running around with

his wife. That was just after the War ended. Guy came to town and got a job and

got to know the wrong woman.

Murder is Never

Simple

But others

tell a different story. Here is what Grace Nelson, an adult at the time, says:

We knew about all of it,

I guess. It started on the other side of us, down around the doghouse. We had a

double house. The Simmons were living over there, and they had all gathered that

night. My, they were making a noise. That happened so much I didn’t pay any

attention to it.

My husband was hostling.

You know what that is? Keeping the engines fired up. I went on to bed, and he

came to bed before 11 o’clock. He said, “I don’t think anything’s going on now.”

Well, we hadn’t been to bed but just a few minutes until we heard someone say

Carl or Boyd got shot. Of course, he had to jump out of bed right quick and get

down there to get the boy down to Mace.

But this Teeter hid. He hid for

hours. He went up in the coal tipple and sat. They didn’t know where he was. The

police came in, but they couldn’t find him until morning. They were all sitting

in this doghouse, and he came in and gave himself up.

“Are you looking for

me?” He said.

They said, “We sure

are.”

But they were drinking

that night, and this boy— he was a young boy and a friend of Carl’s son—I mean,

he was . . . maybe it wasn’t intended for him when he shot him? We don’t know.

The boy tried to take the gun, and they were wrestling around or something.

he was a young boy and a friend of Carl’s son—I mean,

he was . . . maybe it wasn’t intended for him when he shot him? We don’t know.

The boy tried to take the gun, and they were wrestling around or something.

Dorie Powers

recalled the incident as well:

I don’t think he

intended to kill that boy. He was drinking—him and his wife and his son, I

understood him and his son had been into a racket, and his son throwed something

at him and then run. He run for the doghouse. And Carl took his gun to go up

there.

They told me that if

Gainer hadn’t jumped up—I reckon to take the gun up maybe—that he would never

have got hurt. I guess he really meant to shoot his son, but Gainer jumped up to

take it up and that was when he shot him. But I don’t think he really meant to

shoot anybody. When Carl was sober, there wasn’t a better man. And he was a

good, he and his wife both, were good friends of ours, and if he hadn’t been

drinking—really I don’t think he meant to hurt anybody just scare his son was

all he probably meant to do.

Moonshine in a

Dry Town

There is one

point missing in that story, however. There were no bars in Spruce, so where did

a person go to get drunk?

Johnny Sharp

talks about his family and how they made moonshine to get by:

Living was tight. My

brothers would cut kindling wood out of the old mill. They’d cut kindling wood

for people, and they’d carry coal a nickel a bushel for people. Whatever money

was picked up like that was used to live on.

Well, you couldn’t live

on it, and my mother would take in any washing money that she could get and wash

for people. She’d wash for the store man, Fitch Simms, but that doesn’t go very

far, so we’d make our home brew—five gallon of home brew—and sell it twenty-five

cents a quart.

My brother Lee then

decided he would make a little liquor. First we borrowed a washing tub, and

copper—used a piece of copper tubing and wrapped fur around it up at the side of

the creek. Used the creek water trough for the cooling tub, right above my house

at the side of the creek. It’s in the summertime: set the ash barrel outside and

made it.

Made a few runs like that, and finally we

built . . . my brother Sterle decided he would dig him a hole in the bank and

put him a little building and put it back in the bank so the mash wouldn’t

freeze—it would still work—which we did. After the mash was run off, after you

run your liquor off, then the washing tub was hid good.

The work was carried to

the top of a pine tree and hung up at the top of the pine tree so everything was

put away. And we kept secret paths. Furthermore, people didn’t pry onto us too

much. They didn’t feel welcome sometimes in that area. That’s the way we made a

little bit of liquor, sold it for a dollar a pint, 75 cents for a twelve-ounce

jar. We sold not as a big business but just to keep food on the table. And in

the summer time we would pick berries. You took a bushel basket, buckets, and go

up there and pick blackberries and put in that bushel basket and carry them off

and sell them for 25 cents a gallon.

Homebrew, Old

Hen, and the Law According to Spruce

But that was

the hard stuff. Most everyone had access to “homebrew.”

Ed Broughton

recalls how they made it:

‘Bout everybody had a

stone crock behind the burnside. We called it home brew if you wanted to cap it,

but if you just wanted something that you didn’t want to bother capping, you’d

make something like old hen. You’d just throw raisins in there, a bunch of old

grapes—anything that would ferment—leave it and let it work. And it was good

home brew too!

You have to know the

right amount of ingredients to put in it, and you got to have a good ear. My dad

knew. He could put his ear down there and he could hear that fizz, you know.

He’d hear that last fizz and say, “It’s ready to cap. Let’s put the cap on her.”

You’d cap it and after about thirty days, you’d pop one of them. You got some

pretty good beer. It was better than what you could buy.

It seems

surprising that the company would allow something like this to go on, but Pat

Dugan relates how Spruce was pretty well self-governed:

Do you know what Frank

Imes and Ikey Calain and them boys told me when I went in there? I walked into

the yardmaster’s office that evening, looked the group over—I mean, I knew quite

a few of them—but there were a few I didn’t know. So he looked up and said,

“Well you finally made it.”

I said, “Yeah, I don’t

know for how damn long, but I finally made it. I’ll give you just as good as you

give me. I may stay longer than you or you may stay longer than me. We haven’t

gotten around to that.”

He said, “Well, I’m

going to tell you one thing I want you to remember.” He said this in front of

everyone. “I don’t want you to forget. You remember the three monkeys?”

I said, “Yeah.”

I said, “Yeah.”

He said, “You just play

that part—that you never hear nothing, never see nothing or know nothing. No

matter what. I don’t care who that man is, you play that part.”

Now it’s not like a

mafia outfit, don’t get me wrong. It was family. If you had trouble, it didn’t

do me no good to go out and broadcast it. Let’s keep it right here in Spruce. We

didn’t have no law officers. We didn’t need none. We were our own. If you went

out and killed a deer or you did this or you did that, sure you went and ate,

but you didn’t ask no questions. Just like Harry Johnson, he’s dead and gone,

but Harry and I went hunting in that laurel thicket. Burt Weese and all of them

told me to be careful so I wouldn’t get lost in there. I could see how you could

get in that laurel thicket and continuously walk in circles and never get out.

Anyway, while we were up

in there hunting, Harry said, “What are you looking at, Pat?”

“This is a damn funny

thing,” he said. “That’s a salt block.”

I said, “What would you

need a salt block back in here for?”

“Now never you mind.

Just forget that you saw it.”

So that evening when we

come in, Frank looked up at me and said, “You got nosey today didn’t you?”

That’s the way that it was. We got a game warden, lived right in the

yardmaster’s shanty. Man by the name of Hobatter. He practically told me the

same thing.

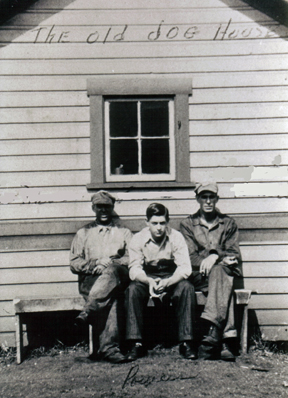

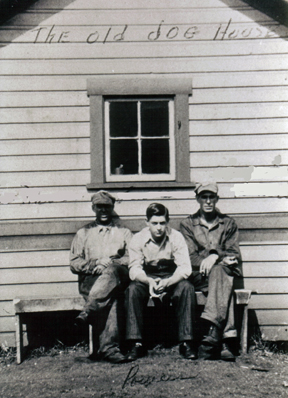

The

old dog house in Spruce, which is the location of the death of Boyd Gainer.

Pictured is Charlie Fansler and Bud Teter in the door and Okie Powers is in the

back. Photo courtesy Dorie Powers.

Tall Tales of Old Jack

It seems like

most everyone you talk to remembers the town’s misfit, the outcast who might

have been a little crazy but was definitely very odd. In Spruce, this man was

Jack Arlington, and it seemed like everyone had a story about old Jack.

Johnny Sharp

recalls:

One time Les and I went

down to Hopkins Mine and went to the top of the hill there. We explored all

around. An old man lived up there, Jack Arlington. He was as black as the black

in a beetle. His hands were real black, and his beans were awful good. He fed

us, and we fooled around until almost dark and went off the hill.

It’s about

six-and-a-half miles down there after you get off and hit the railroad. So a

half a mile off the hill down to the railroad, he gave us a carbide light and

one filling of carbide. We started up the railroad track, stayed as long as we

could, and got up to milepost 84.

There was a pile of ties

at the side of the track that looked like a bear standing up. We made a great

big circle up against the hill and come back from the railroad track and up the

track we went again. We got to Big Run bottom and there was a deer, or something

made a racket that we knew was going to get us. We ran like scared rabbits, got

up to the bridge—four miles down—cut off there, and there was a big rock heap we

knew about.

We went out to that rock

heap—boy we done stuff—got us a fire going and stayed all night. The beans, we

had the beans for supper! Stayed all night and the next morning, and when we got

stirred around there after daylight, got the frost shook off of us, Les headed

for home. He had enough of it. We took back down the river and stayed all day

again to have a bite to eat.

I’ll tell you, Jess Hornick . . .

Jess’s brother Hess said, “Jack, come up in the morning and I’ll get your

breakfast.” Jack went up. Hess was by himself so he mixed up a big bunch of

pancake batter and baked the pancakes for Jack for his breakfast—fried him some

eggs and some bacon.

“Oh yeah Jack, you can

eat these.” And he piled some more on his plate. Hess kept the bacon. Hess baked

seventeen hotcakes for him besides the eggs and the bacon.

Finally, Jack said,

“Hess, I can still chew but I can’t swallow!”

Jack would start just as soon as

he got started out of Spruce. He would go out of Spruce limping, He had his sack

on his back and his cane, and he would go just a limpin’ and a hoppin’ and a

limpin’ and a hoppin’.

He’d get back down there

about a half a mile below Spruce. But he got down there talking to himself. A

log went across the creek just before he went up the incline, and he thought

that was the best way for him to go, otherwise he went down the incline and

walked straight up—he’d walk this log to get out of there. The incline you know,

they run straight up.

So he walked out to his log.

“Jack,” he said, “You can’t walk that log.”

“Why sure I can walk

that log.”

“No Jack, you’ll fall in

the creek.”

He’s talking to himself

and answering: “You’ll fall in the creek.”

“No I won’t fall in no

creek. I can walk that log.” And he started. He got out on it, and he fell in

the creek. “See you ole son of a bitch, I told you you would fall in the creek.”

Did you hear about the

time he laid down? He started from Spruce. There was a switch went in just this

side of the twin bridge just before the double tracks. They put coal down there

a lot of times. He went down there and got tired and just crawled—I think it

sprinkled rain or something on him—but he just crawled in under there, laid down

and went to sleep.

I guess they come up

there, uncoupled that train and pulled a whole train of coal right down. He laid

right there on the track, between the two rails, and he laid there. He was a

small man, and he just kept real quiet and laid down real flat and never moved

and let them pull a whole train of coal on him. Well, that’s not saying the six,

eight cars—that’s one thing—and when you start out with sixty or seventy out,

that’s something else.

He’d sleep in the sand house on

the warm sand. He’d want to get up and get out of there the next morning, and

we’d lock him in the sand house. One time Wagner and I used to get firecrackers,

and we got the sand up in the oil house. We had a string of them fire crackers,

them little ones; we’d hold them together.

We got him after us

first—run down by the engine—let him see us. He started to climb out to get us.

We dropped the firecrackers out and he hit on a step. They started exploding.

That knocked them off, and they just scattered on the ground. One would go off

there and one would go off here. Boy he was jumping up and down. I’m telling you

when he got straightened out; we never got a cussin’ like that.

Apparently no one knows what happened to Jack. Some say he

went to the retirement home down in Elkins. Rumor has it that before he moved to

Spruce, he had a wife and three kids that drowned in a flood down in Florida. No

one really knows what Jack’s real story was.

Travelers in

Town

Other folks passed through town, some

interesting, some dangerous.

Bert Weese

recalls a traveling barber:

There was a tramp barber

that was a real case in Spruce. The tramp barber always came in. He really was a

barber, but he sold clothes. He came just every so often. He’d come in and take

your measurements for some boots and stuff, and he’d cut your hair. He mostly

wanted some food and a place to sleep.

Nobody ever knew his

name. Have no idea where he was from. He’d be in Elkins quite a bit and

Marlinton, everywhere. He was just really a bum, I guess, because he’d come in

and stay at everybody’s house that he could stay. He was just a walking Hobo.

What his name was . . . I don’t know, but he had money stolen off him. He had

worked and had money stolen off him.

He had a brother living

in Richwood, and he had worked in the camps and saved up quite a lot of

money—had a pretty good chunk of money on him—and somebody stole it from him and

he started looking for the guy. He would go everywhere. He would come by maybe

10 o’clock in the night, pitch dark. It could be raining or anything else, and

he’d keep walking. Wouldn’t stay. I picked him up in the road and hauled him up

to Mace, and he’d take right off over the hill, hit the railroad track at 10

o’clock. He was looking for the guy that robbed him. He’d go in and stay maybe

one maybe two days before he’d come back again; go clear through Richwood,

Webster Springs. He walked like that for years.

Johnny Sharp

remembers a hobo coming to stay at his house:

Johnny (his father)

lived in that house there at the lower end of Spruce and one night, Carolyn was

probably a year or two old, he brought this man in. He rode in on a train—hobos

would come in on the train—he came in and wanted me to fix him something to eat,

so I made him sandwiches and things.

He went out and Johnny

told him, “You come out and we’ll give you breakfast in the morning.” He

didn’t

come back in the morning. A couple of days later somebody gave us a detective

magazine, and there was that man’s picture in that detective magazine. He had

killed a man and kept him in a room for three days covered him with talcum

powder so the odor wouldn’t . . . I told him, “Don’t you ever, ever bring no one

into this house again.” Yeah, back in those days we fed everybody.

-

Clown: A Belsnickle costume. Belsnickle is a dying tradition of German roots.

People would dress up in costumes and travel from house to house and people

would try to guess their costumes. Candy would also be distributed. Much like

Halloween, this tradition took place during the Christmas season. Grace Gainer

explains, “We used to dress up and go to people’s houses dressed up like a

witch. We would go anytime, we called it goblin. We would get dressed up and

put masks on our faces, and they would ask us in, and we’d go in and talk for a

bit. And then we’d leave.” Photo courtesy Leo Weese

Life and Times in Spruce

Those were different times. People shared what they had more

because times were rough for everyone. Here are some telling stories about the

material quality of life back then.

Tom Broughton recalls some of the costs of living then:

It was a job fixed so

there wouldn’t be no raise in wages. In ‘31 they cut it down to $1.90 a

day—eight hours a day. We was working ten hours a day, six days a week when we

started: $2.50 a day is what we started out at.

Then, the way they

worked it, they cut us down to eight hours a day instead of ten and took 5

percent off of us to $1.90 a day. They charged us a dollar a month for the house

coal and water at Spruce. We had no electric. They had water in the house, and

we got the coal at the tipple. We had to carry that a short ways. That wasn’t

much money.

Bert Sharp recalls:

Do you want to see how

much I made in two weeks? Thirty-nine cents an hour. I started out as an

apprentice machinist. When we finished in four years, I made $1.04. There was

two weeks—September 15, 1942—amount earned was $48.49.

Stafford ran the jewelry

store in Elkins. If you wanted to buy a gun, he’d get you a gun. Anything you

wanted, Bill Stafford would get for you and then deduct it. He took $4 a month

out or every two weeks for her wedding ring.

You could go to the A&P

store and fill the taxi up with groceries for 13–15 bucks every two weeks, and

we’d live on that. I’d get bread off of the bakery, two day old bread, and put

it in the deep freeze. You had to pinch your pennies. I worked my vacations to

pay for some of the bills that had accumulated.

People didn’t

need as much money back then. After all, rent was only a dollar a month!

Lucille Ward

explains the Spruce water system:

We had oil lights, burned coal in the cook

stove for heating. We did have running water in the house. In the summer, in

order to keep things, we had a tropper built out in the back

porch—a little

enclosure—and kept the running water going through that. It kept the food cool,

because it was good cold water.

porch—a little

enclosure—and kept the running water going through that. It kept the food cool,

because it was good cold water.

I’ll explain to you what

that water system was. When the West Virginia Pulp & Paper Company built the

town back in 1903, right above the town of Spruce was a little stream. And up on

the back on the mill side, just up above the houses, is where the stream came

off the hill. Up there on the bank they had built a little concrete dam and made

a place to gather their water.

They dammed that up, and

they did actually build a concrete dam. They ran a pipe out of it and the

gravity feed. Even the houses—we talk about it being a flat place—actually,

where the houses started, it was downhill enough that the water would keep

flowing down through the houses.

Back at this time when

they built the town, it was actually unusual to have running water like that.

There is some talk . . . some people feel that because of the convenience of

putting running water in the houses, this was something to get people to work in

the logging days. Like a luxury—to have running water in the house. It was

thought that maybe the paper company could manipulate people to think we have

running water.

Washday for some Spruce kids.

Photo courtesy Dorie Powers

Winter and Home

Remedies

There wasn’t

much money for entertainment. Besides drinking or hunting, there wasn’t much to

spend extra money on.

Ed Broughton

describes winter entertainment:

A lot of the men and

women went along with this. That pond we showed you, the West Virginia Pulp &

Paper Company had a good pond. There was a lot of water in that. The winters

were so cold that pond would freeze over thick. We could build a fire right in

the middle of that pond, leave it burn all night, and it would never burn

through. We would ice skate on that and stay out all night. We’d have sleds. The

women would get out and pull their little kids on them sleds, and we’d have a

wonderful time.

The weather

got pretty bad in Spruce. There are many stories about how bad the snows got

from time to time. Here are chilling tales of life in the highlands, the first

from Wanda Sharp and the second from Devane Cussins:

Wanda Sharp

recalls a great snow:

One year, it was either

1945 or 1946, it

snowed so much that when we got up that morning and looked out

the upstairs window, all you could see was the neighbor’s roof and chimney. We

climbed out the upstairs window and slid down the snowdrift in boxes. Dad dug a

path from our kitchen door to the outhouse and the coal shed, but the walls were

so high it seemed like a long tunnel to me. I don’t remember any of us ever

missing school because of the snow. We always made snowmen, snow angels, played

fox and geese and jumped off the hill behind the schoolhouse about forty feet

into the snowdrifts. It always drifted real high back there.

I don’t remember having a cold too

often, but when we did get one, Mother would grease our chest and back with a

poultice made from grease, camphor, turpentine, coal oil, and Vicks salve.

Sometimes she’d make an onion poultice for us, and we would stink to high

heavens, but it worked.

Photo by Leo Weiss

Leave the Faucet

Running

Devane

Cussins tells about frozen pipes:

You always had to keep

the sink water running in the wintertime to keep it from freezing. Once Edith

and Pappy left for the weekend, and the sink drain froze shut and the water

over-flowed onto the floor and froze. When they came back, they couldn’t get the

door open because of the ice on the floor. They had to climb through the window.

Pappy built a fire to thaw the ice, and then Edith had a mess to clean up.

The winters were fun

because the snow would blow through the windows of the schoolhouse, and we could

skate on the wooden floors. The schoolhouse sat on high ground above Spruce by

the railroad tracks, and there was a cut where the tracks went through the hill

behind the school. During winter, the snow would drift against the banks, and we

could jump off the bank into the snowdrift. Or the kids that had sleds could

sleigh ride down a path from the school, past the girl’s privy toward the

doghouse.

One winter the snow got so deep in

the cut behind the schoolhouse that it was up level with the banks on the sides

of the cut. The railroad had a big snow plow, which could be pushed ahead of an

engine to clear snowdrifts from the tracks. One of the engineers, I don’t

remember who it was, was going to clear the drift with the snowplow.

I guess they thought it

would be a fairly easy job. But the first time they tried, the plow went in only

so far and stopped, and the engine began to spin. So they backed out and decided

to get up more speed. When they tried the second time, the snowplow and the

engine both got hung up in the snowdrift. So they had to couple another engine

to the rear of the first engine to get the plow out. I am still not really sure

how the snowdrift was cleared.

Isolation and the

Move to Slaty Fork

At times

Spruce was completely shut off from the rest of the world, which wasn’t that

bad, unless you had a medical emergency. A doctor lived in town full time during

Spruce’s first era, but there weren’t enough people to justify a doctor during

the second period. If people got hurt, they were taken by railcar to Mace where

they either met a doctor or traveled to a hospital.

Leo Weese

shares:

See this scar above my

eye? When I was little I was chasing three girls with a double- bladed axe, and

I fell on it. They loaded me up on a motorcar with a big Turkish towel on my

head. And they took me to Mt. Airy, put me in a vehicle, and drove me down to

Elkins to see Doc Butt and Dr. Mauzy. They looked at me, and they said, “Hell,

no use in numbing it now …” And they just took a needle and sewed it right up.

But I bled a whole Turkish towel full.

Spruce wasn’t

meant to last. Trains grew larger and the railroad more efficient, and

eventually, the town no longer needed to exist. In 1951, almost all of the

houses were moved out of Spruce at one time, and many people moved down to

Laurel Bank, or as the Railroaders called it, Slaty Fork.

Johnny Sharp

relates:

It was a move, which

allowed your train to operate over more miles. You got more mileage from Elkins

to Spruce. You wasn’t getting the hours out—you could run it a lot faster and

still get eight hours work. And if you went on to Slaty Fork, you could still

make it in eight hours, so they got the use of a man for another fourteen

miles.

Leo Weese

remembers:

Everybody moved from

Spruce at one time—except for the track people—in one big caravan. They brought

cars from as far away as Elkins. And then, there was a lot of local folks, like

in Bowden, Bemis, Durbin, Mt. Airy, Cheat Bridge, and all of them had five-six

men and track cars and whatnot. All these cars came in, and it stretched from in

town in Spruce all the way around up to the phone box up there, probably a half

mile. Everybody moved out one time. And I moved out with them.

A few homes

remained at Spruce for several years. Nancy and Lee Sharp moved back in 1952 for

a while after getting married, but eventually Western Maryland burned the rest

of the houses down. And so Spruce has sat for approximately fifty years, slowly

returning to the forest from which it came.

Recently

there have been efforts to list Spruce in the National Registry of Historic

Places. Remains of the old mill and some other building foundations are still

visible. The site is also of archeological significance, and parts of Spruce

have been excavated. Spruce today can be accessed by foot from Snowshoe or the

Monongahela National Forest as well as by an excursion train called the Cheat

Mountain Salamander.

-

A

current view of the town of Spruce, taken from the same angle as the painting

and the panoramic photographs, with fifty years of decay added. Richard Sparks

writes, “Seen from the north are the remains of Spruce in April, 1994. Most

prominent are the poured concrete endwalls of the mill powerhouse. The man is

standing on a small smokestack; just above his head can be seen the foundations

for the endless chain conveyor that went from the mill, east to the banks of

Shavers Fork. To his right, at the base of the hill, is the concrete and timber

lined spillway of the millpond. The townsite is the open area across the

river in the middle distance.” Photo

courtesy

Richard Sparks

A

current view of the town of Spruce, taken from the same angle as the painting

and the panoramic photographs, with fifty years of decay added. Richard Sparks

writes, “Seen from the north are the remains of Spruce in April, 1994. Most

prominent are the poured concrete endwalls of the mill powerhouse. The man is

standing on a small smokestack; just above his head can be seen the foundations

for the endless chain conveyor that went from the mill, east to the banks of

Shavers Fork. To his right, at the base of the hill, is the concrete and timber

lined spillway of the millpond. The townsite is the open area across the

river in the middle distance.” Photo

courtesy

Richard Sparks

Link

to Chapter Five

Spruce,

West Virginia (elevation 3,853). - The town of Spruce, located high in the

wilds of Cheat Mountain, is thoroughly intertwined with West Virginia’s

industrialization. In many ways, the town typifies industrial history in the

state. Born during the logging boom, Spruce transitioned into a coal town and

now exists as a tourist destination.

Spruce,

West Virginia (elevation 3,853). - The town of Spruce, located high in the

wilds of Cheat Mountain, is thoroughly intertwined with West Virginia’s

industrialization. In many ways, the town typifies industrial history in the

state. Born during the logging boom, Spruce transitioned into a coal town and

now exists as a tourist destination.

”

”

One morning Pauline and I went to

get water. On our way back to school we got some craw crabs, lizards, tadpoles,

and frog eggs and put them in the bucket. We brought them back to school and put

them in the water cooler. We told the kids not to drink the water, but we’d all

snicker every time Mr. Bell got up to get a drink.

One morning Pauline and I went to

get water. On our way back to school we got some craw crabs, lizards, tadpoles,

and frog eggs and put them in the bucket. We brought them back to school and put

them in the water cooler. We told the kids not to drink the water, but we’d all

snicker every time Mr. Bell got up to get a drink.  on

on Tom

Broughton, an engineer, recounts:

Tom

Broughton, an engineer, recounts: he was a young boy and a friend of Carl’s son—I mean,

he was . . . maybe it wasn’t intended for him when he shot him? We don’t know.

The boy tried to take the gun, and they were wrestling around or something.

he was a young boy and a friend of Carl’s son—I mean,

he was . . . maybe it wasn’t intended for him when he shot him? We don’t know.

The boy tried to take the gun, and they were wrestling around or something. I said, “Yeah.”

I said, “Yeah.”

porch—a little

enclosure—and kept the running water going through that. It kept the food cool,

because it was good cold water.

porch—a little

enclosure—and kept the running water going through that. It kept the food cool,

because it was good cold water.