“They’d have cakewalks and square dances. There was always something going on. I think people felt sorry for us in the larger towns. But we felt sorry for them ‘cause they were missing out on what we were doing.”—Calvin Shifflet

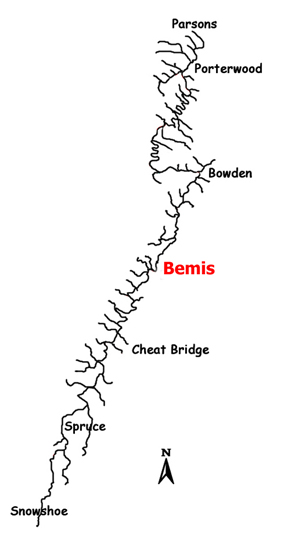

Calvin Shifflet in the Glady post office/store. Photo courtesy Karen Sutton.

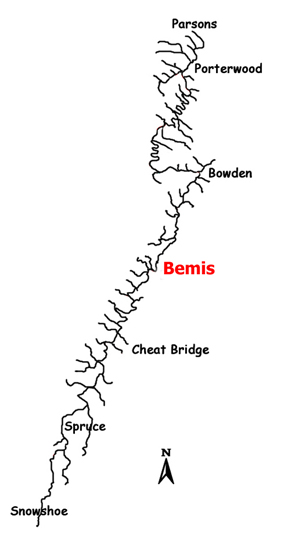

Local historian and storyteller Calvin Shifflet of Bemis, West Virginia, has spent his entire life on the Shavers Fork, except for three years in the Army and a couple of years thereafter. Calvin chose to stay close to home, even though he certainly could have made more money elsewhere. But he doesn’t regret it for a moment.

Talking with Calvin, I could ask one question and listen for five, ten, sometimes fifteen minutes as he wove the tale of his life. Through a series of interviews, Calvin shared his life stories, intertwined with a history of Bemis and the local area.

Bemis started off as a railroad construction

camp called Camp Fishing Hawk. Construction of the forty-seven-mile Coal and

Iron Railroad from Elkins to the C&O [Chesapeake and Ohio] connection at Durbin,

Pocahontas County, started in 1900. First train serviced pulled into Fishing

Hawk in late 1902. I think it was in July or August.

Bemis started off as a railroad construction

camp called Camp Fishing Hawk. Construction of the forty-seven-mile Coal and

Iron Railroad from Elkins to the C&O [Chesapeake and Ohio] connection at Durbin,

Pocahontas County, started in 1900. First train serviced pulled into Fishing

Hawk in late 1902. I think it was in July or August.

The town was built by the Rumbarger Brothers: Robert R., John J., and Frank T. were sons of Jacob Rumbarger Sr. There was also a fourth son—he must have been a younger one—Jacob Jr. In 1904, a large sawmill was constructed at Fishing Hawk, which is where that large stream comes down the lower end of Bemis and dumps into Shavers Fork of Cheat River.

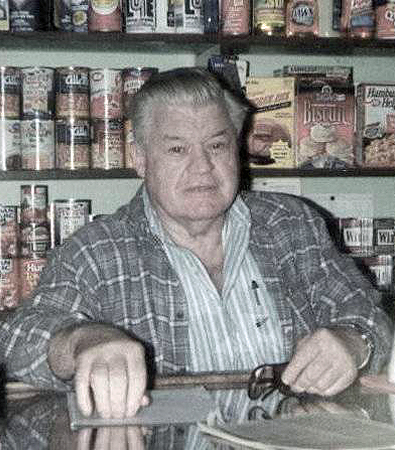

-The town of Bemis just 6

years after the sawmill (just left of center) and post office were built.

The

original town plan consisted of thirty employee houses, a large company store

(just right of center)

and four large houses for company executives. Photo

courtesy Calvin Shifflet.

When they got a post office in 1903, they

dropped the Camp and called it Fishing Hawk and with the help of Senator Stephen

B. Elkins had the name changed to Bemis in September of 1906. The name change

was an honorary sort of thing. J.M. Bemis’s general manager, Mr. Koch, wrote to

Stephen B. Elkins and thanked him for changing the name.

had the name changed to Bemis in September of 1906. The name change

was an honorary sort of thing. J.M. Bemis’s general manager, Mr. Koch, wrote to

Stephen B. Elkins and thanked him for changing the name.

This information says over thirty two-story houses were built for company employees. A large two-story company store with offices above was built and four large two-story houses were built for company officials. School and church was also constructed immediately. A steam-operated forty-five-kilowatt direct-current electric-generation plant was purchased from Alice Chalmers’ company to provide electricity for lighting houses and the sawmill.

A large band mill was soon in use for increased production. This operation produced lumber, pulpwood and tanning bark. January 1, 1906, a formal buyout was made by J.M. Bemis & Sons from Bradford, Pennsylvania. The purchase price, $600,000—$100,000 down and half million balance—was to be paid in lumber shipments of 10,000 feet per year until the balance was paid to Rumbarger Brothers. This operation continued until February 1, 1921. The Bemis family then moved their operation to Robbinsville, North Carolina. It was still in operation in the 1990s.

The town church, built in 1904. Photo courtesy Calvin Shifflet.

The first schoolhouse and church was built in 1903 by the Rumbarger family. No saloons or drinking establishments were allowed until 1921 when J.M. Bemis and Sons moved operation. The first schoolhouse was destroyed by fire in approximately 1931; the second school was constructed immediately as a three-room school. It was a ten-year school until 1942. The original land plot contained forty-five acres and it included the entire town.

I have a picture of the original store. It says H.J. Bemis General Store. That was Henry Bemis, J.M. Bemis’ son. In the windows you can see Rumbarger Brothers. The doctor’s office was upstairs and I understand Mr. Bemis’ office was upstairs. But you could still see Rumbarger stenciled in the windows. The Rumbarger Brothers, instead of Mr. Bemis, mostly built the town.

They came from Coketon over in Tucker County. In fact, that was part of the name of the operation . . . Coketon Lumber Company. Also some of the deeds were to Rumbarger. The railroad came into Bemis in, I think, August of 1902, and they had already bought this timber. I understand it was a small circular mill there.

The Rumbarger Brothers immediately installed a large band mill. According to this one book I have, Bemis sawed more timber than any other mill in this area. They moved out to North Carolina and West Virginia Pulp & Paper Company took over the operation and ran it until 1926 or 1927. They hauled everything from Bemis back up to Cass ... the big operation up in Cass. This was later the Mower Lumber Company operation.

First mines were opened by Monserat Coal Company in the early 1930s and later Davis Coal and Coke, then the Walker Coal Company, which moved operation to Bemis in 1939 and ‘40. This mine closed for good in November of 1950.

Billy Green Coal Company is located between Bemis and Glady on Shavers Mountain; opened in 1935, ceased operation in 1942. Several other smaller contractors mined for coal up into the 1980s. Walker Coal Company ran two shifts employing approximately sixty to eighty men. The Billy Green Company employed about the same. Both mines were unionized around 1940. After the Bemis outfit left, we didn’t have electricity until November of 1950.

It was a big let down after the mines shut

down 1950 in November. The younger people started moving out. Older people,

seemed like, stayed on at Bemis. They didn’t have anywhere to go . . . just

stayed and hung on, including my parents. But when I was growing up, there

was around 250–300 people up there, same as Glady. One time for a project

for school we did the population of Bemis. I think it was right around 300.

School

was the Center of Everything

They had what was called a ball diamond. I

remember they had a volleyball team, a softball team, pie socials . . .

Seems like there was a pie social every month to raise money for whatever.

PTA [Parent Teacher Association] Socials helped finance the school.

Bemis,

with school and playing field at left.

The Bemis lumber company donated the

property for the school. It was in pretty sad shape. The principal, Jason

Meadows, and the older boys cleaned it up. There were all kinds of holes and

rocks to move to make it so you could play anything—ball or volleyball. It

seems to me there was a certificate that used to hang in the hallway. It was

a Model A School . . . ‘Course it was a secondary school. I don’t know how

many schools had that certificate but Bemis did because they were doing so

many extras activities. They’d have cakewalks and square dances. There was

always something going on. I think people felt sorry for us in the larger

towns. But we felt sorry for them ‘cause they were missing out on what we

were doing.

Head of

the Cheat River

Bemis had a ball team in 1908. In my time

it was just softball. We didn’t have enough room or flat land to have a

really good ball diamond. We had teams even after I came back from the Army.

We played Highland Park in Elkins, and we played the prisoners in

Huttonsville, the medium security prison. We played them about every summer

and got beat pretty bad ‘cause they had a really good ball team.

When we couldn’t play anyone else, we’d

play Whitmer. We’d play ball awhile and fight awhile. I remember the last

game I played over there turned into a donnybrook, over what I don’t

remember. I was twenty or twenty-one. Before that we played Glady. They’d

let school out and

In the summer, we all learned to swim in

the Cheat River, as we called it. In fact, I didn’t know it was Shavers Fork

till I come out of the Army. The “head of Cheat River” is what the residents

in Bemis always called it. All the boys, girls too I guess, learned to swim

almost as soon as we started to school. One way or another you’d learn or the big

boys would pick you up and throw you out in there, making sure you’d swim

back to the bank or they would help you. We ran around and built log cabins

in the woods, swung on grapevines and fished, naturally. All the young boys

in this area grew up with a fishing pole and a gun in their hands to fish

and hunt.

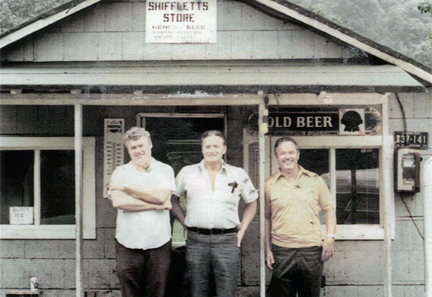

Calvin and two of his brothers, Orual and Clarence in front of Calvin’s

Bemis store. The store opened in 1961 and still serves the small community

today.

Bemis Weathers Floods

They built the floodwall in Bemis in ‘08. I

heard someone talk about it and was always wondering where it was. I was

looking at this photo one day and I found that thing. Forty-two. I can

remember very well. It rained all night at the head of Fishing Hawk, washed

all the track out. It (water) was in that big brick building in Bemis—clear

to the first floor—it was a full basement.

It shut the mines down. Walker Coal Company was

running full blast then, and about all the people even at Glady was employed

there. It washed all the track out; the mines were shut down. They had to

rebuild the grade where they’d just cut it right along Fishing Hawk. It washed

all that out.

In the mines, I remember, it drowned one pony.

They had mine ponies. One of the ponies was trying to get over to the other side

where the other ponies were. I remember us kids going to see where that pony was

lodged in the trestle. No lives were lost, but we lost the one pony.

They were probably a good week getting that

roadbed built back. All that coal from Hickory Lick and up at the head of Valley

Head—Bethlehem Steel mines—all came through Bemis. The tannery, the lumberyards,

pulp yards . . . they couldn’t haul nothing till they got all the track rebuilt

at Bemis. I remember my Dad -- it seemed he was working day and night.

The water from Fishing Hawk came right through

the middle of town. It was not in anybody’s houses.

It came down the road, run down through the side and back into Cheat River at

the lower end of town. There was a big culvert and ditch in the middle of town

put in for the millpond. The railroad culverts carried a lot of the water as

well as the culvert. I remember getting up that morning -- school went right on,

kids walking through the water up to their ankles. But it was just a mess for a

lot of people to clean up in their yard.

In the ‘85 flood, it tore at the bridge in

Bemis and almost was ready to come down into town. The rain was more

concentrated in the exact south so it affected the Shavers Fork more than it did

Fishing Hawk. It didn’t come over into town like it did in ‘07 and ‘42. The

trees—it washed gobs of trees out. And then they’d go through this

superstructure: the old bridge would rattle and creak and bang. Everybody would

think it’s gone and it held right on. They’d embedded it into the solid rock

over here, and on this side it was just a cement abutment. It’ll be there for

another hundred years till something moves it, if ever. The state road came in

and repaired it. It messed all this up. It ruined the beach. Now it’s full of

boulders and rocks.

They gave the [evacuation] order in ‘96. A guy

called me and said the water at Cheat Bridge was now higher than it was in ’85,

but the river started to go down. It was up in the cabins in Bemis, didn’t hurt

anything, about like ‘85. All over the floors in two, three camps.

Here it is [in his diary]: “The National

Weather Service notified people to evacuate. My brother and the Coopers

refused.” It was on Friday January 19, 1996. “Water dropping fast. Tore up the

field behind my store. Rolled my brother’s truck over into my property.”

He come over in ‘16 and stayed until ‘18, then

he went back to Virginia. Him and Mom

-

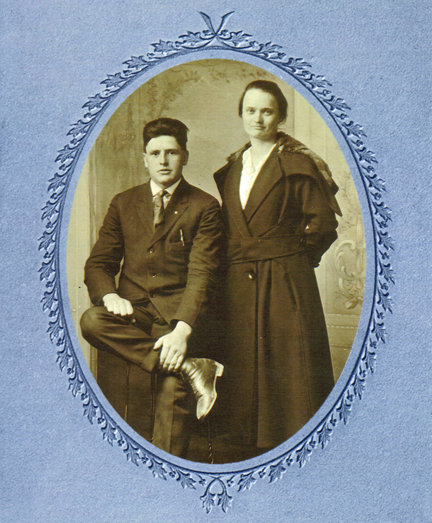

Joseph and Rosa Hansbrough Shifflett, Calvin’s Parents. This picture was

taken in Beldor, Virginia in 1919-20. They later moved to Bemis in 1925 and

lived there until their deaths in 1965 and 1983.

Photo courtesy Calvin Shifflet.

My dad was always going back, going back. He’d

get a little too much to drink, and he was like that song about that one crazy

guy who made the songs . . . Daddy’d let out a big whoop—and I can’t remember

how it goes now—he’d say, “I’m going back to old Virginia, getting out of West

Virginia. I’m going back to old Virginia . . . ”

He’d thump his chest and say, “I’d whoop any

son-of-a-bitch from West Virginia.”

We’d say, “Dad, the three of us is from West

Virginia.”

And he’d say, “Well I’d whoop any of you, too.”

He was a section

hand through Bemis. Never went any farther than Bemis. Three of his brothers

were foremen at one time, another one at Cheat Bridge and one other one

somewhere else. They’d hire just about anybody, but you had to have a foreman

who knew how to do everything.

There was six boys in our family, just three of

us left. Six boys and no girls. People used to ask Mom if she wished she had

some girls around the house and she said no. ‘Course we grew up pretty rough in

Bemis, you know. She just turned us loose and either you make it or you don’t.

With the girls it was a different story.

All of us went into the service except the

oldest—he was born crippled, badly crippled—and he lived twenty-four years

before he died. He couldn’t talk. They never could figure it out. We took him to

a couple different places but they never could figure it out. If it was today,

I’m sure that there would be all sorts of scientists wanting to study him. But

back then it was during the Depression, and Mom had to take care of him like a

baby for twenty-four years.

It was pretty

rough living in these two towns. If it wasn’t for Franklin Delano

The name of it was Jewell’s Department Store

and you could buy anything there. We had two years of high school, as we called

it, and the teachers had to stay there during the winter. They had a couple

rooms and medicine, restaurant, post office, store, hardware. That’s

where you had to go to get your “relief.” They’d give you bags of flour, real

rough coarse flour. It wasn’t really refined all that much back then.

Calvin with his dog, as a boy in the 1940’s. Photo courtesy Calvin Shifflet.

And powdered milk. I really liked that powdered

milk because it was better than no milk I guess. We had good clean spring water.

I can remember coming home from school, walking from school to the house, and

I’d have a sandwich and some of that powdered milk. It wasn’t white looking like

it is now; it was always green looking. But I really liked that old powdered

milk. Now I won’t have nothing to do with powdered milk, powdered eggs, powdered

mashed potatoes.

They’d give you bags of rice, cans of peanut

butter. You had to mix the peanut butter. It’d be solid, and oil would be on

top. It was just like that with margarine—you had a pack of red dye, orange

dye—and you put it in there and mixed it with your hands. It wasn’t a thing

except shortening, and you’d mix it up. I used to love to do that and Mom liked

it because I’d be helping her too. I’d take that little packet of powder and

sprinkle it on the margarine and turn it over and sprinkle the rest. You take

your hands and knead it, and that was your margarine. The government stopped

that because it wasn’t very sanitary. Even the restaurants were doing it that

way. No more squeezing the margarine. Back then there was an open-topped pitcher

with milk to put in your coffee but they put a stop to that too.

That relief truck saved the day in Bemis and

Glady. The farm folks did all right, but in the city—everybody had a little

garden—that wasn’t enough. We called it Roosevelt’s relief truck and boy when it

come, it’d subsidize you. You could get by. They’d even give you clothes. I got

a picture of me, in W.P.A. work suit. It was khakis, like army khakis, but it

was one piece. I called it a relief suit. I’m about five and there’s a picture

of me watching some folks playing volleyball. They had nowhere to go and no

money to get there. Talk about hard times.

The Depression ended in ‘38–‘39—they say on the

talk shows and radio and whatnot—but not in Bemis and Glady. That was ‘41–‘42.

All the eighteen to twenty-year-olds were heading for the service. It opened up

jobs and made jobs getting ready for the war. Most everybody went to Baltimore

and Cleveland.

World War I,

according to the old timers, was when the first coal mine went in. I think it

was Walker Coal Company. They had mines south of Bemis down at Flint. Then it

started to peter out at Flint so they moved to Bemis in ‘39–‘40. They had a huge

company store that is tore down now. The mines ran until November of ‘50.

There was still a lot of coal, but they had a

hard time selling it because they had a hard time washing it. It [coal mine]

supposedly was shut down until they put washers in and they never re-opened it.

I don’t know what happened.

Walker’s mine was on Cheat Mountain and Billy

Green’s was on Shavers, right above Bemis, at the top of the hill. They ran in

the ‘30s and part of the ‘40s and they strip-mined until just a few years back.

And they had a deep mine, but that ended the mining period then.

Auger holes: a series of auger

holes going into the mountain after a strip mine job is finished. Auger holes

were used once the ‘overburden’ became too much and strip mining was no longer

economical. The height of the auger holes is determined by the size of the coal

seam. This mine was located near Fish Hatchery Run.

I was in a mine one time. My oldest brother, he

was in day work, where what you loaded was what you got paid. So he’d go in on

Sunday. Them days you had to drill your own holes and load, I think they called

it Monabelle or something, like dynamite. They’d shoot down what coal was cut

and you could load what cars were there—they’d hold about two tons—and you’d

load it on up. I went in on that Sunday . . . that hot wire

was over your back all the time. The coal was never more than forty-some inches

and everything was on your knees and crawling. We come through a water hole—that

was at least 440 or 660-volt hot wire—if you touched that it probably would have

fried you in that water hole.

You just done your own shooting, you see. Back then you just got

paid for what you loaded, so you loaded that car. If you had two cars you loaded

two. Maybe you had four ton, and you’d like to have three cars. Well, some days

you could get it, and some days you couldn’t. You had a little weight-check with

your number, with a hole in it. You’d stick that in that nail and you’d stick

that on the car—it was oak or locust, some real hard wood—and you’d drive a big

nail in it and bend it. You’d carry your weigh-checks on you: it was like a

safety pin but bigger, and it had your checks. You’d take it off and stick it on

your nail.

They had a sheet up in front for eight, nine,

ten—and you was number eight, and they’d have one ton 1,200; one ton 1,400, and

then you got credit. At the end of the day, they’d total it up and turn it in to

the company store—it set across from where the brick building was. Everyday the

supervisor, he would bring all those weigh-sheets down, and that’s what you got

paid by. They took out some for light and for any dynamite—they’d charge you for

that.

When you shoot the coal, you could see the dust

in the air, and no masks. No one wore any masks. They had a little air

circulating, which was required—the federal mines inspector made sure they had a

little air circulating—but it helped very little. You’d shoot—you’d have those

lights with the battery over your head—and you’d shoot and get back out of the

way and touch it to the battery to shoot. Then you’d walk back over—the coal

dust was still up in the air—you know you was breathing it, even way back over

there.

Eventually you went in, putting the coal into

the cars, pushing the track on up to the face and throwing the dust off to the

side … That was my one day experience and I decided that wasn’t going to be my

career. I know we went in and we loaded up what he shot down. And then we

crawled out and washed up. The mine opening was right next to Fishing Hawk—the

creek there that runs into Bemis—and we washed up.

That was my mining career. For one thing, I

couldn’t stand it going back in under the mountain—three feet high with a hot

wire going above you—working with that dust around you.

You went to the company store, and if you

stayed in the red, they’d tell you what you could buy and what you couldn’t buy.

Most of them sent the kid with a big list. If you were in the red lines, you got

what they wanted to give. If you were in the black, more power to you, anything

you ordered, that was fine.

A lot of guys didn’t have the tonnage or maybe they missed a day,

and that put them behind. I know lots of them there that never even had an

envelope. They had a brown envelope: your time with deductions. They didn’t even

ask for it; they knew they had it coming. They stayed in the red. But that was

the way of life.

Boy that song . . . that fits the company store

in Bemis. That, “Sixteen tons and what do you got?” Only thing is, you could

never get sixteen tons because you could never get the cars. And the thing is,

the guys that were in the red got the cars over you. They was in the red and the

other guys were taking money and going to Elkins and spending a lot of it. So

you might get two cars and that guy in the red got the third car because the

superintendent, his mother-in-law owned the mines. His daughter took care of the

time, and her and her husband run the company store.

Army

Life at Fifteen

I already had my stuff fixed up to get into the

military. I was fifteen, and I had it doctored up so I was eighteen. I washed

that coal off and said, “Boy that’s the first and last trip into the mines for

me. There has got to be a better way to do it.” But that was the way of life

there. Your Dad take you in; your older brother take you in. They had to take

you in until you got a miners card.

The next day I caught the school bus down to

Elkins, and instead of going to school, I went to the recruiting office. That

night I was in Fairmont, and I’d been accepted. The next day I was in Ft. Knox,

Kentucky. There was a recruiting office in Elkins. It was at the post office. My

brothers were in the Navy, but I didn’t like the water so I headed for the Army

office.

I was born in 1933, and I took a little bleach

and dropped on it with an eyedropper. This fellow was advising me and told me

what to do. He told me to put some white vinegar to neutralize the bleach and he

lined it up in the typewriter. He said all you have to do is hit that ‘0’ and

that jumped me from fifteen to eighteen. And that put me in.

So I went down to the sheriff’s office and he

said, “Looks like you’ve been doing some doctoring here.

I said, “Yeah.”

And he said, “You want to get into the Army

that bad huh?”

I said, “Things are pretty tough at home, and

I’ve got to get into the service.”

When we got done he said, “Fifty cents.”

I said, “I ain’t got but a nickel.”

There was a box where they put the money in for

the Photostat. He reached into his pocket and put fifty cents from his pocket

into the box.

He said, “Good luck to ya.”

Years and years later, we had a drink at the

VFW [Veterans of Foreign Wars], and he had forgotten all about that. He had

gotten pretty far in politics.

He said, “There was several boys that did

that.”

Only bad thing was that my Mom and Dad didn’t

know where I was. We didn’t have phones, and I couldn’t call them no way. But

the first thing they made you do in the Army was to write our folks. And they

would make sure that you sent that letter out. My Mom could have had me sent

home in a heartbeat but she didn’t.

I cleared the issue out later on because I

didn’t want to bamboozle the government by getting Social Security three years

early. After I got out, they drafted me again, and I had to explain everything.

They sent it over the draft board, let them know what was going on. I was

walking a tightrope for a while there; I was thinking that I was going to have

to go and pull another two years! Done pulled three.

I never heard no more about it. I was worried

about it for a bit, about them withholding my veteran’s benefits, but it never

did catch up with me.

Calvin served in the Army Signal Corps

for three years, then worked in Baltimore for a couple of years before returning

to Bemis. He “couldn’t stand the cold out on those piers shifting those barges”

in the winter, and after he went to work for Glen L. Martens, he couldn’t stand

the heat: “It [Baltimore] was the hottest place in the summer I ever was at.

It was the coldest place in the winter I was ever at either. Just a different

cold. And the heat? Just muggy. You couldn’t hardly get your

breath.” Matt: How’d you meet your

wife?

Calvin:

We started going together right after I went into service. I came back on

furlough. She was still in high school. Her and her cousin and a girl who lived

across the street in Bemis, they all went and lived with two aunts of hers in

Baltimore. That’s where they would stay until they got situated.

I was working on

the railroad, the B&O Railroad, and we got married. I still was working on the

railroad. We stayed two years, and I come back because you could hardly get your

breath.

They had just sent

those big matador missiles to Cape Canaveral, Forida. We’d put them in big

crates and fasten them down and cover them with tarps—we had these big grayish

brown tarps.

One day it was so hot you couldn’t get your

breath. I drug a box of tools and a fan around on a buggy. I come in that night,

and we had our first child born, a girl. I come in and she said, “What do you

think about going back to Bemis?”

I said, “I was ready the day I come out here.”

So I said, “Next week Monday I’m going to turn in my time.” And I turned in my

two weeks notice.

Back home

there were few jobs, but Calvin found work at Dutch Oven in Elkins, among other

work,

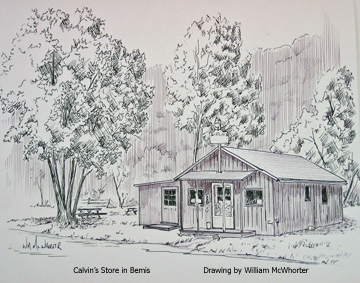

I built the store in Bemis in 1961 and still

operate it. My wife and I took this store and [Glady] post office over in 1977.

We’ve been here ever since. It was founded in 1886, one of the older Post

Offices in West Virginia, I would say.

You’d be amazed at how many toothbrushes I sell

over here at the store. They come all the way over here, and they forget their

toothbrushes, especially the women. During those summer camps, they come in and

they say, “Boy I hope you got toothbrushes and toothpaste.”

‘Course I sell as much of that as anything else

you can think of. Or they run out of ketchup or mustard or they need some

-

George Rowan was half Indian and was a bit of a drifter. He did odd jobs

in the community and lived there for a while. Occasionally he would perform a

bear dance. Although he certainly was eccentric, he was a trusted member of the

town. Cathy Phillips, Calvin’s daughter, remembers that he was like a surrogate

grandpa to her.

Bemis Returns to Camping

The town was

almost completely dead until the hunting camps and fishing camps all started.

Last count I had there were over 200 between Glady and Bemis, counting those in

the town of Bemis. I counted along the road and places you can’t see then

checked with Ron White. He has a big campground, and he had about fifty.

That rejuvenated Bemis. I probably wouldn’t be

running my little store if it weren’t for the hunters, the fishermen, and camps

like that. Lots just come in for the weekends and keep it going enough where I’m

open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. I used to be open seven days a week but

there’s just not that many full time residents.

In fact, the last time I counted twenty-seven

in Bemis and thirty-two in Glady fulltime who get their mail through this

office. There wouldn’t be a Bemis there now except for the camps—hunting and

fishing—tourists. Most of the tourists just want to get away. They come quite a

bit even in the winter months if it’s not too bad.

-

Calvin’s grandson Chris Phillips in 1980.  What little studying I did was by a

kerosene lamp. The school was the center of everything. Every night the

school would be open. We had about five teachers when it was a ten-year

school. They had a ten-year school up until the middle of World War II. And

then they started hauling the kids out to Elkins. I did eight years at

Bemis. Right as I started riding the bus, they shortened it to an eight-year

school, I think it was.

What little studying I did was by a

kerosene lamp. The school was the center of everything. Every night the

school would be open. We had about five teachers when it was a ten-year

school. They had a ten-year school up until the middle of World War II. And

then they started hauling the kids out to Elkins. I did eight years at

Bemis. Right as I started riding the bus, they shortened it to an eight-year

school, I think it was.

we’d play over there. Then next time it was our turn to

go over to Glady and play. We’d play right below where the school building

set. Back then there was always something going on.

we’d play over there. Then next time it was our turn to

go over to Glady and play. We’d play right below where the school building

set. Back then there was always something going on.

Photo courtesy Calvin Shifflet.

got married in ‘19, and then he worked on

the railroad over there on the Norfolk and Western Railroad. In ‘25 his brother

was the boss foreman in Bemis, and he wrote him, and I don’t know if Dad

expressed that he wanted to come back, but he wrote him and said they had an

opening if he wanted it. So we come back in ‘25. I said we, but I wasn’t born

yet. My three brothers were born in Virginia, and they come over in ‘25, and we

stayed here. The three oldest were born in Virginia, and the other three were

born in Bemis.

got married in ‘19, and then he worked on

the railroad over there on the Norfolk and Western Railroad. In ‘25 his brother

was the boss foreman in Bemis, and he wrote him, and I don’t know if Dad

expressed that he wanted to come back, but he wrote him and said they had an

opening if he wanted it. So we come back in ‘25. I said we, but I wasn’t born

yet. My three brothers were born in Virginia, and they come over in ‘25, and we

stayed here. The three oldest were born in Virginia, and the other three were

born in Bemis.

Relief at Jewell’s Department Store

Roosevelt, the

people up here would have starved. When they brought that relief in, they would

stop in Bemis and then on to Glady. I still remember the place—in Bemis it was

the Dahmer Store—that huge big brick building that they just tore down a couple

months ago.

Roosevelt, the

people up here would have starved. When they brought that relief in, they would

stop in Bemis and then on to Glady. I still remember the place—in Bemis it was

the Dahmer Store—that huge big brick building that they just tore down a couple

months ago.

Coal Mine in Bemis

Photo courtesy Monongahela

National Forest.

Red and Black Lines at the Company Store

Hot and Cold in Baltimore

Back Home: Dutch Oven Days, Bemis Store and the Night Club

for a number of years. But life in and near Bemis always pulled him

back. Eventually he opened a store in Bemis and became post master/storekeeper

in nearby Glady. Here’s how he describes it:

for a number of years. But life in and near Bemis always pulled him

back. Eventually he opened a store in Bemis and became post master/storekeeper

in nearby Glady. Here’s how he describes it: milk

or coffee. I sell quite a bit of coffee. About everybody wants the real coffee,

not the instant. They’ll come in and—especially the old timers—they’ll come in

and ask if I got any boiled coffee; not the other stuff, the boiled coffee. That

means that they don’t want the instant. A lot of the old timers, they just throwed coffee in the can. I used to do it when I was in the Army. It boils for

four–five minutes and the grounds just settle on the bottom. It was pretty

horrible coffee. There was no filters, and the coffee was almost always too

strong but it was coffee. Boiled coffee, the old timers called it.

milk

or coffee. I sell quite a bit of coffee. About everybody wants the real coffee,

not the instant. They’ll come in and—especially the old timers—they’ll come in

and ask if I got any boiled coffee; not the other stuff, the boiled coffee. That

means that they don’t want the instant. A lot of the old timers, they just throwed coffee in the can. I used to do it when I was in the Army. It boils for

four–five minutes and the grounds just settle on the bottom. It was pretty

horrible coffee. There was no filters, and the coffee was almost always too

strong but it was coffee. Boiled coffee, the old timers called it.

The right line went into a

tunnel that came out the other side of Cheat Mountain

and headed up to Durbin,

the left followed the Shavers Fork further upstream