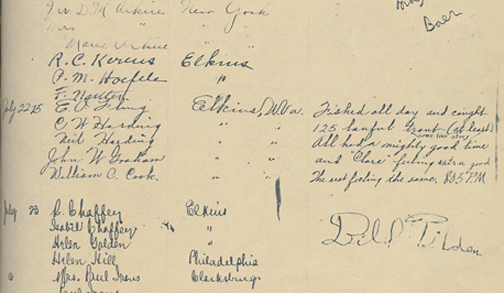

“One day board and lodging at Club House. Departed Morgantown Camp Aug 29, 1899. Three coons bagged by Mr. Bell. Barbeque containing coon stew, coon soup, and coon hash. 10 a.m. Have continued en route to Everglades, Florida.”—Joe Reed, Cheat Mountain Club Log Book, Aug 22, 1899

The Shavers Fork watershed is a valuable piece of West Virginia’s commons, one that has served people, from locals to tourists, for generations. While the Monongahela National Forest owns much of the land, a good portion of the private land is open to a larger community, sometimes just to friends and family, sometimes to anyone.

As early as the 1880’s, outdoorsmen were drawn to the wildlands of Cheat Mountain near the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike (now U.S. 250). Some of them built a lodge called the Cheat Mountain Club, and enjoyed catching upwards of a hundred fish a day. Soon the trout population had to be supplemented to supply plentiful fish for the guests, and the hatchery pictured below was built. A mile or so of Shavers Fork is still stocked for Cheat Mountain Club guests, one hundred years later.

Fish hatchery at Cheat Mountain Club - Carl Frischkorn, a former board member of Cheat Mountain Club said of the fish hatchery they had there, “I guess what they did was hang meat above the hatchery and let the maggots get to it, and the fish would eat the maggots. Which doesn’t make the fish sound very attractive for humans to eat…”

Some thirty miles downstream, in Bowden, the State of West Virginia operates a fish hatchery which supplies 22% of the state’s stocked trout. The Bowden Fish Hatchery was established by the Federal Government in the early 1930’s; West Virginia took it over from the US Fish and Wildlife Service in 1997. According to Curtis I. Taylor, Chief of Wildlife Resources Section, West Virginia Division of Natural Resources:

“Trout fishing is a tradition in WV. Families spend many quality hours together enjoying the outdoors while pursuing hatchery-raised trout. Trout fishing has a significant economic impact to the state and particularly to small communities close to popular trout waters. Trout fishing generates $57,900,000 of economic input to the economy of WV. It is estimated that trout fishing supports 658 jobs in the state.”

From a letter to Mr. Harold Parsons, WV Department of Environmental Protection. January 13, 2005.

Fish Tales

“I probably fished more on this river

when I was eighteen years old in a day than I do now, living on

the river, in a

year. I mean, I fish some, but then it was just a burning, burning desire. It

was all I thought about. I just had to be here. It was the most important thing

in the world just to be here.”—Henry Nefflen

the river, in a

year. I mean, I fish some, but then it was just a burning, burning desire. It

was all I thought about. I just had to be here. It was the most important thing

in the world just to be here.”—Henry Nefflen

One of the Shavers Forks’ greatest bounties is the wildlife it supports, including some of the best fishing in the state. It is the coldest stream of its size in West Virginia, which helps support a native brook trout population. Although threatened by acid rain, this population remains temporarily stable because piles of crushed limestone dumped on the banks of tributaries slowly disperse into the water, moderating its pH.

Lower downstream, the river

warms, and its waters support rock and smallmouth bass as well as various pan

fish. Many other species of fish, as well as amphibians and insects, inhabit the

river, but trout is the main quarry that interests the fishermen.

Midsummer Trout Fishing

Henry Nefflen, born in Elkins, has lived near the Shavers Fork his whole life. He shares the story of his best day ever fishing:

We came out one time—we were juniors or seniors in high school—and we were driving then. We came out and the river was turning just a little bit milky. It was summer; it was mid summer, and we came out and we fly-fished from that old swinging bridge up to about right here, and I think between us we caught about fifty–sixty trout. All really, really nice trout. Brown trout. And we kept every single one of them.

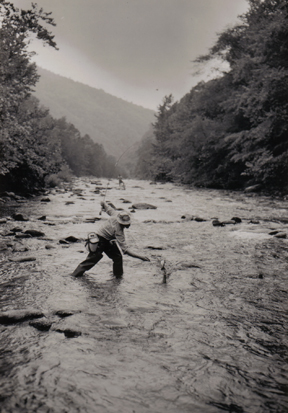

A fly fisherman concentrates on his casting on

the Shavers Fork. June, 1927.

Photo Courtesy Monongahela National Forest.

I mean, we were redneck fishermen. Catch and release wasn’t even a concept then. I struggle with it sometimes still, this urge—but I don’t really anymore—I take what I want to eat. I don’t have a problem. But back then, we kept what we caught. I can remember just hoarding them like they were gold bricks or something.

And my mother—I bet she was so mad at me—I’d come home, and I’d try fifty different ways of freezing them to try to keep them fresh. I remember freezing them in blocks of ice, and I’d freeze them and about six months later Mother’d be throwing them out.

But that day . . . I have never had a day of fishing like that in my life, I mean ever. I don’t know where all those trout came from. It evidently had rained someplace upriver, and it made the water colored a bit. It wasn’t raising. It was just milky, not muddy. The color turns more like khaki pants.

Now they have taken so much timber and stuff it just turns muddy. It becomes more of a tea color. When it’s just slightly muddy, you’d call it milky because it looked like it had milk in it. But you don’t see that color anymore; it’s more of a red-clay mud kind of color. It helps fishing—you can really slay the fish. When the water is like that, it’s indicative of increased food in the water. It dislodges nymphs and puts earthworms in the water, and puts the fish in a feeding mode. The barometric pressure affects it, and the visibility is down.

Anytime you can see a fish, chances are you won’t catch it because it can see you. So if you fish, you always walk upstream because that’s how fish lie. When the water is discolored, it gives you an advantage. They might be feeding more actively. And another thing is that they are less likely to see your line. A lot of times when the river gets muddy it means that the fish are going to start feeding more actively, particularly if you have had long dry spells. But that day, the water really wasn’t coming up much. It was just milk colored.

That day the brown trout weren’t at all particular. You know, sometimes it’s real hard to match the hatch. They’ll pass by your fly, and right after that they’ll rise on something else. But not that day. It was one of those days that fly-fishermen dream about. They were just shredding flies, just tearing them up.

We had another guy with us, and he was a

minnow fisherman, he never caught a single fish that day. We have a particular

way of stringing fish up here. You take a minnow about one-and-a-half to two

inches long, and you make a rig. You use a loop of line, attached with a swivel

to your line.

We had another guy with us, and he was a

minnow fisherman, he never caught a single fish that day. We have a particular

way of stringing fish up here. You take a minnow about one-and-a-half to two

inches long, and you make a rig. You use a loop of line, attached with a swivel

to your line.

You need a needle with a slit in the eye. You hook the loop with this slit, using the needle you thread the loop through the minnow, take the needle off, then attach a double hook, pulling the minnow down to the shank of the hook—almost like a rubber minnow. It works with saltwater fish too, and it works like a charm. Any sporting goods store in this area has those needles, but you won’t always see them in other areas. It’s popular here in Randolph, Pendleton, and Pocahontas counties.

Goldens- These golden trout are mutant rainbow trout and are prized for their

beauty. This shot was taken by Henry in his Fishing Store in Bowden.

Photo

Courtesy Henry Nefflen.

River Music

Henry goes on to recount another unforgettable moment on the Shavers Fork:

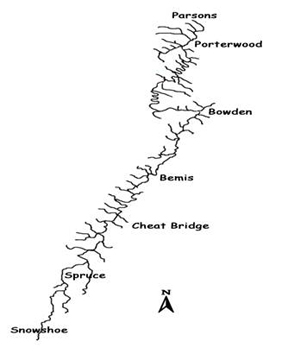

I remember one time I was fishing up around Linan. It was actually at Harper. That’s a hole near there that I really used to like. There is a siding below McGee Run. You gotta walk like three, four, five miles down the tracks to get there to it.

I really loved fishing there. Sometimes two,

three, four, five of us would go, and we’d stay in an old telephone booth

there—it wasn’t much bigger than an outhouse—but we fixed it up so four or five

of us could sleep in it. Sometimes, I would go over by myself, and there was a

really, really great hole to fly-fish. It came around, just like if I was facing

you, the stream would be coming from my left, and it would come around. There

were rocks at the top, then it flattened out, but there was no slack water. I

don’t know if you ever fly-fished, but there weren’t any parts that were tricky.

You could get a good drift down the whole

hole. And the hole was big—it was

probably eighty to a hundred yards long. The far bank was where the channel ran,

but in the evening when a hatch came on, the fish

would be rising everyplace.

hole. And the hole was big—it was

probably eighty to a hundred yards long. The far bank was where the channel ran,

but in the evening when a hatch came on, the fish

would be rising everyplace.

I remember I was there one day, it wasn’t in the evening. I don’t think I was fly-fishing, I had a spinning rod, and I was using minnows. And I could hear this singing, just as clear—I mean it was beautiful—it was the way that the water was coming down and echoing in the chamber formed by the rocks.

It was a beautiful, beautiful, beautiful melody. It was so clear, but you couldn’t distinguish any words. It was a vocal—it wasn’t like an instrumental—it was choral, but it was clear as crystal. I was mesmerized. I mean it was just at that one place that you had to stand. If you moved away, then the noise changed so it was just water.

I tell ya, it was really, I mean, I always

feel tranquil. Even in the winter I go down and trap even though there isn’t

much action. Just being on the river, just wading . . . You know, it just has a

real tranquilizing effect on me. But that time, I still remember it to this day,

and that was in my twenties. I could hear the words just as plain as can be, but

I couldn’t distinguish them. It would have been nice to be able to reproduce

that, but it was one of those things that just happened. I doubt that there was

any audio equipment anyplace that could have recorded that.

Jim Bazzle recalls fishing back then,

“Actually one of the specific memories that I

have is of when we used to camp right along the water and be awake all night,

excited about the opening of fishing season and standing there and waiting for

the sun to come up enough that you could see and getting your line in the

water. And that was a big deal.”

Tale of the Sunken Six Pack

Bill Thorne, a member of Trout Unlimited, a nonprofit organization that works to conserve trout habitat, writes about an adventure he calls the Sunken Six Pack:

It was the early ‘70s, and I was fishing down Shavers Fork from McGee Run with a friend. We were about two miles down, and we started finding parts of a boat or a canoe. There was about half of it one place, and a partly broken paddle and a seat cushion were also found. I think I still have both. Just below where most of the wreckage was scattered was a long, deep pool. It was real swift and the water was high, but we could see something bright in the bottom of the pool. The water was too swift and deep to find out what it was, so we went on, wondering about the whereabouts and condition of the passengers of the craft.

We fished there often, and the next week we were back and the water was down low enough to make out what looked like a pack of pop or beer. The water was still much too high to get it so we fished on, wondering about the crew of the boat who without a doubt had quite an experience during the breakup of their watercraft.

The next week I was alone fishing the Shavers Fork, and the water was lower than before. I approached the pool with something in the bottom and could make out a six-pack of Bud. Since the water was much lower, I decided to see if the “treasure” was damaged. I cut me the longest pole I could find, which was about fifteen, sixteen feet long, with my penknife.

With a lot of hard work—what a guy won’t do for a free beer—I was able to move it. I had to get the pole in the water far above because the swift current would push it downstream. When I would bump it, the current would take it a foot or so. I kept after it until I was able to get it to shallow water. I had the treasure, beat up a bit but not destroyed.

I never found out what happened to the boaters who lost the boat and gear.

Bill remembers another one of his unusual adventures:

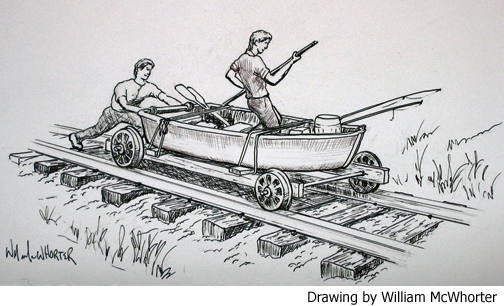

There was once a town named Harper with a railroad siding about eight or nine miles below McGee Run. A friend of mine and I planned a trip and wanted a way to take enough equipment and supplies to stay a few days. I devised a plan that would use my ten-foot aluminum boat and a set of wheels to run the railroad tracks. No one had heard of this so I thought it might be fun. I took a set of four mine car wheels and used an engine lathe to remove most of the metal and put them on axles that went through a wooden frame.

About the third week of May 1975, we took all of our equipment and supplies and loaded all of it in the boat along with the frame and wheels and crossed the Shavers Fork at McGee Run. Then we put the frame with the wheels on the track and fastened the little boat with the supplies on top. People who were there at McGee Run had never seen anything like the contraption we had and may have thought us crazy. It took a little adjusting to get the wheels spaced just right, but I had made plans for that and it was no problem. It rolled real well and before long we were at the Harper Siding setting up our tent.

Some one had told us the High Falls was less than a mile away and we decided to fish to there before breakfast the next morning. My friend likes to eat before he does much, and it was about 11 o’clock before we ate because it was three miles to the falls. I thought he would conk on me before we got back. It was a great start to the excursion.

We fished up and down the river and enjoyed the peace and quiet that was only disturbed by the occasional train that would rumble by sometime in the middle of the night. We looked around the old ruins and found very little sign of anything ever being there.

I was able to spend some time where I had never been and that was special. There were plenty of nice fish, and we caught more than enough to satisfy our desires. We also spent the quiet evenings by the fire talking about not having enough places like this. It was very relaxing to be in the wilderness.

The day it was time to go back up

the tracks, a repair truck went up the tracks so we had to try to time our trip

so we would not run into the truck on the tracks. We thought they might be

quitting about 3 p.m., and so we planned on being back at McGee Run well before

that.

The day it was time to go back up

the tracks, a repair truck went up the tracks so we had to try to time our trip

so we would not run into the truck on the tracks. We thought they might be

quitting about 3 p.m., and so we planned on being back at McGee Run well before

that.

We soon found out our contraption did not go up the tracks as well as it came down. The slight grade made a lot of difference. Whereas we could give it a push on the way down and it would go a little ways on its own; it had to be pulled or pushed all the time now. Despite this, we still made good time, and were moving right along. My friend had stashed a cold adult beverage for us in a culvert along the way, and since it was very hot, he was anxious to get there.

We were going around a bend and came face-to-face with the repair truck coming down: our greatest fear. This was without a doubt the most nervous moment of the trip. I did not know if the truck could stop quickly on the tracks, but he stopped real quick. And they all set there and had a great laugh while we unloaded our boat and then the wheels by the track. We reloaded and made it to the drink before my friend foundered, and then, back to McGee Run. Because we did something different, it was very exciting and fun. Who says you can’t take a johnboat down Shavers Fork?

Fishing back in the day seems like quite the experience. Few rules and the Shavers Fork’s remote location made fishing excursions serious business.

Jim White explains how he used to hike up from Cass and fish the headwaters back in the 1940s:

They called it Pocahontas. Camp Pocahontas. And from that camp they built that road clear across to Linwood, which is on 219. But halfway between where that camp was—up here two miles at the intersection—up to the top of the mountain where you crossed it and come down . . . Halfway between that point and here at the camp you came up on a flat place where, instead of climbing, you came around the mountain.

Right there, years ago, they logged that place, and there was an old logging road that went around the side of the mountain and came up within a half mile of the top. So we followed that old logging road, and then climbed that top, which was almost like trying to climb the side of a building. Then we’d go over and down the other side and fish the headwaters of the Shavers Fork. We’d fish clear out to Spruce and then walk back to the railroad.

By the time you got to Cass you was pretty sure you were never going to do it again. And then you’d end up doing it again in a couple of days. That was probably, let’s see, about fifteen miles. And that was rough walking. Walking along a stream like that is the worst walking conditions you can get into.

You never caught a lot, well, sometimes we caught a mess of fish, but sometimes you hardly caught any. We always enjoyed it, and the only way to get in there was to walk. So you hardly ever had any interference. It was quiet for miles. It’s hard to find that anymore. I don’t know what year Snowshoe started, but a couple years after they got it, they put it off limits.

Jim White shares another humorous story:

We were up there fishing, and we hadn’t walked from Spruce that day—I mean the headwaters of the river—we had either caught a ride or walked up the railroad and just went over there to just fool around. There was a good hole just where this bridge had been and pretty deep water. And we were just fooling around in there, just fishing, and we couldn’t get nothing.

One of those old logs—when the ice had broken—it had broke this log and shoved it up into the air. It was sticking out over this hole so we decided there wasn’t no fish in there, or I did. My brother-in-law—he had more patience than I did—he was fooling around with an old spinner there. I told him, I’m going up that thing and see if there are any fish up there. I climbed up that thing, and I saw a rainbow trout that—the marks on that thing had to be four inches wide. That trout was twenty inches long! And boy my brother-in-law never forgave me.

He said, “I would have caught that fish if you’d have stayed out of there.” I don’t know what happened to that fish.

We caught some rainbow up there. Somebody said that rainbow are not native to this country, but somehow they got up there a few miles. You caught some big rainbow, but that was a BIG one. I don’t even mention it anymore because my brother-in-law gets so mad. We never saw much game up there.

The only thing that was up there mostly was a lot of grouse. I’ve grouse hunted a time or two up that river. I’d go up there—I never could hit a grouse very good—but it was good grouse country. There was things up there for them to feed on—and bear—we saw lots of sign but never did see one. We saw lots of bobcats though. I never saw one when I was hunting. I only saw them when I was fishing.

I didn’t hunt up there too much. I went up there a couple of times walking that railroad track grouse hunting. It was good deer country, but it was so vast in there, and if you killed a deer you never could get the thing out. We enjoyed that, especially the quietness, not many people could go fifteen miles to go fishing—not in that country. But there was a lot of beavers up there—not when we first were up there—but later them beavers put a great big dam up at the headwaters right about where that lake is where Snowshoe is now.

They had a big dam, and they had the water

backed up quite a ways. If you went up in the springtime, you could catch fish

out of that dam. You could get in there and, one year early, my brother and I

went up there. It had warmed up early in March, and I told my brother, I said,

“Let’s go up in there and let’s go over to the beaver dam and fish.” And we went

up there and it was gone. See those things only stay for so long. It had rotted

out and wasn’t there.

- The type of brook trout that fly fishermen dream about. However, this one was caught by an electric current sent through the river. Dave Thorne, a graduate student at WVU is conducting a survey of the native brook trout population on the upper Shavers Fork. Photo courtesy Shavers Fork Coalition

Trout Fishing at the Big Cut

As Jim White said, not everyone could make a trip like that.

Spruce resident Jess Hornick tells a story about his times fishing the river in the late 1940’s:

Me and Sharp would go up there and get what we wanted. We’d go up there in back of the mill up that way too. It runs right into the Big Cut. Do you know the trout can go from Cheat River over and down the Tygart Valley River at a certain time? They could now because of the big water spill that comes right down the center of that cut. And some of it flows into the Tygart Valley and some of it back into Cheat.

I’ve caught trout not more than 200 feet from the end of the cut on the Cheat side. All I’d have to do when the water’s high is go up there and go right on through. I found that pond below the Big Cut as you come down on the right hand side. There’s a big pond in there, and one time I was up there and there was trout in there about eight inches. It was loaded with trout—on the left hand side going toward the big cut. I don’t know what exactly caused this pond, but it was pretty deep and loaded with brook trout.

Ernest Caplinger, you know, lived next to us. When he was a wood hick up at Old Spruce, he said on Sunday afternoons, wood hicks wouldn’t be working, but he would go with the cook, and he would carry the burlap sack. There would be two guys, and they’d come back that evening, and they would have that there burlap sack—all he could carry—for the freezer of the camp. Two of them was fishing, and he was just carrying a sack full of them.

Lee Sharp used to go in the other parts, and he would bring back a basket full. Down below, when I was fly-fishing down there at Twin Bridges about a mile and a half below stream, I had three flies on, and I pulled out two native rainbows about nine inches long. This was a long time ago, about ‘47 or ‘48 when I was working up there.

One time I was fishing with my wife—she’s afraid of fish worms—and I remember we went down Old Spruce there, I baited her hook up there, and she throwed it down and back up the tracks she went. I still remember her running up the track.

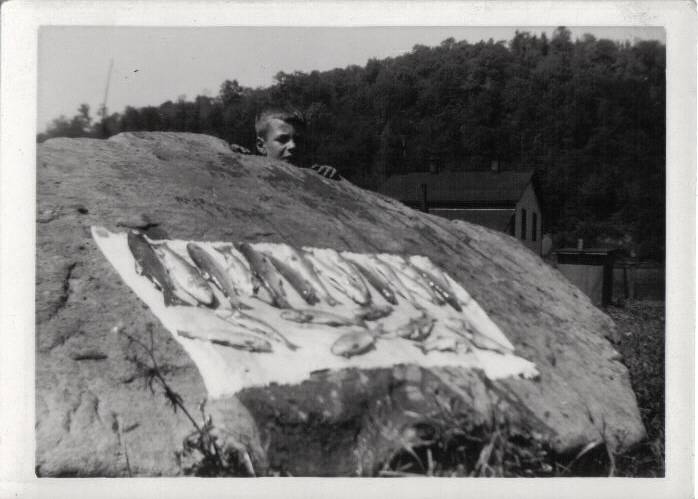

- Haul: Young Leo Weese peeking at a day’s catch of trout being dried out in the sun. Photo Courtesy of Leo Weese.

Stanley Wooddell wrote a memoir in the Pocahontas Times in 1976 where he recalled fishing as a young man and seeing the evidence of the logging that had happened not much earlier:

Our old farm home stood in the early morning shadow of Cheat Mountain about four miles west of the head of Cheat River. When I was about twelve years old, my Dad said, “Let’s go to Cheat River fishing tomorrow.” Early the next morning we rolled two biscuits and ham into a paper bag, took a can of worms and a gallon pail and headed for Cheat River.

The weather was cold, and I worried all the way about wading in the cold river. Fifty-five minutes later we came down the mountain to a small stream about two foot wide.

“This,” he said, “is Cheat River.”

My Dad cut a switch pole about the size of a buggy whip, tied about three feet of line on it and attached a small hook, baited it with a fish worm and dropped it into a small pool the size of a bathtub. Out from under a root came the first trout about five inches long. We worked our way through the laurel and caught a trout in every place we could get a hook into the water. As we fished along, the stream got bigger, and the trout got longer.

We came to an old log landing where briers were all cut off level about five feet from the ground. I asked Dad what long necked animal did this, and he said snowshoe rabbits cut them off on top of a deep snow and ate them. Farther downstream we came to a large log jam in the river, and a lot of the big pine logs were torn apart by black bear looking for ants and grubs. Lots of bears and wildcat sign everywhere.

Fishermen of today who catch from one to three stocked trout can’t imagine what trout fishing then was like as there were so many hungry trout in a hole that when a hook was thrown in, one didn’t know which one he would catch. Eight trout about eight inches were lying in the shadow of a log side by side in the shade. My Dad caught seven of them.

I said, “Don’t be a hog, save some for seed.”

The only food the fish had were black ants

that fell off of logs along the stream. Fishing here was good until the timber

was cut the second time—it let the sun in and the water got warm. Rotten logs

and treetops turned

the water brown, and the trout disappeared.

The only food the fish had were black ants

that fell off of logs along the stream. Fishing here was good until the timber

was cut the second time—it let the sun in and the water got warm. Rotten logs

and treetops turned

the water brown, and the trout disappeared.

Our reward for a hard day’s fishing and a ten-mile hike was a good supper of mountain trout, rolled in corn meal and fried golden brown; a skillet of fried potatoes; a pan of good hot biscuits and country butter; and a pitcher of good cold buttermilk to wash it down.

Day’s Haul- A productive day of fishing. Henry Nefflen says, “That’s a tailgate. That’s a mess of fish caught right there by the store. But that was early, that’s snow on the ground.” Photo Courtesy Henry Nefflen.

Opening Day and Fish for Fun

In those times there was an opening day for the fishing season and having gone through the cold winter without dipping a line, hundreds of fishermen lined the shores come April.

Jim Bazzle, owner of Revelle’s Campground explains:

There used to be that there was an opening day. It was the last Saturday in April I think. An official would come in and they would be at every major access point. They would shoot a gun to let folks know when they could start because there used to be hundreds of people lined up. Then everyone could fish the river. We used to camp right below the bridge to make sure that we had a good spot. That gun would go off, and you could hear a splash in the water.

While opening day has faded into history, locals have tried another practice to maintain a population of fish in the river. Aptly named “Fish for Fun,” it is a catch and release system—one that has been met with mixed results.

Lillie Isner explains:

Oh yeah, we used to go every week. Howard and I did. Well, I shouldn’t tell this, but I will anyway. I was pregnant with my oldest child and Sunday—she was born the following Wednesday—I was up the river fishing. I thought my sister-in-law was going to have the baby for me, PSSH.

I just never thought . . . if you got thinking about it, I could have fallen down the river, but I didn’t. Women today maybe could do it. We went fishing every weekend. Then Howard got too old, and we went down to the lower end of the place—they had barbed wire fence down there—and we got down on our hands and knees to get under the fence.

And he got his shirt caught! He got so upset.

He said, “I ain’t going fishin’ no more!”

And so he didn’t. We didn’t go anymore, and when he quit, I quit—unless I go down to Virginia. Then one time they put that Fishing for Fun down here. That didn’t go over. If I catch a fish, I want to keep it. But you have to throw it back. And they call that fishing for fun? I was fishing for fun, but then I want the fish.

Kids Fishing Day

Although the catch-and-release

system does not fill any fisherman’s plate, it does help keep fish in the

stream. Another event is a day set aside for kids to fish.

Although the catch-and-release

system does not fill any fisherman’s plate, it does help keep fish in the

stream. Another event is a day set aside for kids to fish.

Longtime Bowden camper, Boone Hall, describes Kids Fishing Day:

There is probably two hundred to three hundred fish, and each kid gets to catch two fish. If they come to me and haven’t got any, they will catch ‘em. But we stock those ponds, and it’s great. You don’t know what the kids’ll do. Their parents want to take a picture of them, and the kids won’t want to hold the fish. I’ve had thousands of kids hold the fish, and I’ve had two kids that wouldn’t hold it. We fillet them fish.

We get older folks who come in who don’t know it’s for kids, and we have to run them out. This one lady—it was near the end of the derby—and I was helping her boy. I only had two minutes to go, and I got one on. I released the line, and he brought it in. And he caught his two.

His mom, you know, said, “Boy I’d just love to catch a fish. I’ve never caught a fish before.” She said that three, four times.

Well, after he caught his second one, I said, “Would you like to catch a few fish?” She said yes so I cast it out there, and I felt one on, and I released the line and gave her the pole.

And here comes this conservation officer by, and he says, “Lady, this event is for kids only.”

I turned around to him, and I said, “Officer, she’s retarded.” I didn’t know that lady—I didn’t know her from nobody.

And she looked at me, and he said, “Well, fine.”

After he left I said to her, “Well lady, I had to say something!” That’s the best day of my fishing. Every year I look forward to that the most. This year I recruited some football coaches, and they helped me.

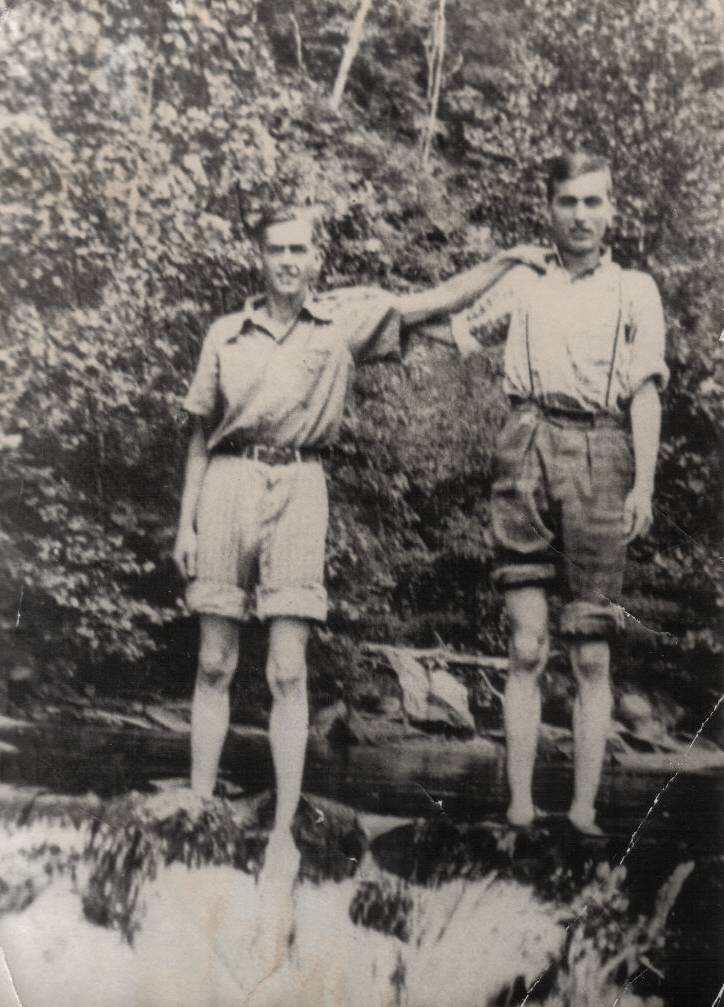

Roy & Howard Shaffer, brothers at the Pettit falls. Howard, on right is two years older than Roy. Photo courtesy Hazel Phillips.

Boone continues:

Fishing this river is very dangerous. I’ve been stuck on a rock on Upper Shavers for about four or five hours, and I couldn’t move. I was very fortunate that I didn’t drown because if I had gone in the water … you cannot swim with waders on. I tried. I always thought that I could do it and swim downstream or something—you can’t do it.

A friend of mine down here—we had a fellow drowned. Two years ago, it was cold, and he had on waders, and he drowned. It was that same summer I got in the water with my waders on—and I thought I could swim—but I had a neighbor there, a lady, was there to get me out.

I’ve caught a lot of fish in here, you know, big ones. Now I enjoy watching other people fish. Now I turn the big ones loose because I’d rather that someone who hasn’t caught any catch one. And I enjoy the kids. There is nothing better than watching those kids fish. There’s nothing better. And when they get a fish on, you don’t know what they’re going to do. They will go off running or they’ll throw their pole—I’ve seen them do it all. It’s real good fun.

I originally started camping up in Bear Haven. We just cleared off a spot and put a tent up. That was ‘57–’58. Then we started camping at Stuarts Park. Then I cleared off a place here and started camping. I hooked up the electric myself and did everything myself—well, me and my wife. Now we’ve probably got about twenty campers down there, and it’s just a bunch of friends. I retired a year and a half ago, and I’ve been up here every week.

Fly-Fishing on Shavers Fork

The “Fish for Fun” idea has its place in some spots on the river. In many others, it is not a very good idea. In any case, people are still scattered throughout the Shavers Fork fishing holes.

Al Krueger, a current Shavers Fork Coalition board member, shares his fishing frustrations:

I fly-fish as much as possible, but I have a frozen shoulder, and I can only raise my shoulder about this high. It gets painful after a bit so I switch to spin casting, which I can do underhand. I used to fly-fish. That’s all I did, but I had to compromise a bit. The problem is, there are some nice fish in the river there, but there are so many small ones. And they’ll bite your stuff—so you catch a couple little ones—but they scare everything else away.

Not last summer but the summer before last—there’s a big hole behind our house—and there were two big rainbows about like twenty inches. I never caught ‘em. I tried everything. I tried going down there at night even with minnows and stuff. I never did catch them. But the problem was that there were so many other fish in there that they’d bite your line. And the rainbows, they’d get smart and they’d just lay there. I never did catch them.

“The hunting is scarce, but the poker

is abundant!”—“Coon” Taylor, Cheat Mountain Club Log Book

Log Book

A watershed is so much more than simply a river. The Cheat Mountain complex is home to many animals—some “threatened and endangered”—and others are so abundant that they have become pests in need of population control. Many of the natural population controls are gone since the majority of large predators disappeared.

Nevertheless, the watershed is known for its game. Whether taking a chance at a trophy buck or snaring beaver pelts, people travel from all over to experience the great wilds of the Shavers Fork of Cheat.

A successful hunting party.

King of the Mountain

Leo Weese tells the

story of “the king of the mountain,” which he ran into near the headwaters:

One time, me and Harley and Marshall were coming up the tram road, and here come a deer, and he would have had to turn his head sideways to get through a door. He had nine on each side. Me and Marshall both had .22 rifles, and he was about thirty yards away. That deer shook his head like that—and Harley shook his cane that he was walking with—and he said, “Don’t shoot, don’t shoot! My God, there’s 250 lbs of meat on that thing, and we’re five miles away from any vehicle!”

But that’s the biggest, evenest deer I’ve ever seen in that country, and I’ve seen a lot of them. And you know what he done? He just jumped off that tram road onto the bank, turned around, and he just snorted, kicked a little dirt onto the road like that. He didn’t run. He pranced like a prancing horse up over the hill, like he owned the country, and I’d say he did. There are still some big deer in there. There were bigger up there, but now that Snowshoe is in there . . .

Beaver and Big Cats in the West Virginia Hills

Deer are not the only game along the river.

Leo relates a few stories of his other hunting expeditions:

I used to hunt that [area] quite a bit—up there at the head of the river. We used to put in at Mt. Airy and go up over Black Run and the tram road, go around Black Run tram road to where that log road comes in; go down there to where it hits Slide Run, to where it runs into the head of the river. We’d go down the head of the river, take that tram road up Cass hill and on into Spruce and hit that Red Creek up there where it hits Spruce—take that up to Big Cut and then take Big Cut there back down to Mt. Airy. We estimated that at about twenty-five miles. We’d start about 4 in the morning and finish around 10 at night. We were beaver hunting. Of course, Mower Lumber Company wouldn’t let us trap, but we’d trap anyway.

There aren’t as many beaver up there as there used to be. Up where the beaver dams used to be is where the ski slopes are now. Just like I said, right there where Slide Run runs into the river—it’s flat up to there—but downstream from there, its nothing but rapids. Looks more like Blackwater Canyon: big boulders and big rocks, and the river drops about a 7-8 percent grade in there. It drops fast. It’s like a big rapids in there. Big rocks. I’ve caught a lot of brook trout in there too, fly-fishing.

Leo relates a story about his belief that mountain lions are still alive and well in the West Virginia hills:

Panthers are still out there. We left a beaver

carcass out there one time. It was a big one, about forty-five pounds. So we

stuck it up on a tree and figured that a wildcat would start eating on it, and

then we’d set some traps and catch it. Well, we came back a half a week later—it

was gone—the whole thing. The tracks were huge. They looked just like a dog’s

but it wasn’t. It was a cat. It dragged the beaver away without dragging the

tail, so that was a pretty big cat. And it made it up over a log with no

problem. They claim that there weren’t any cats in here, but there were. They

would just move in and out of the area. That was in the ‘60s around ‘65–‘67.

Panthers are still out there. We left a beaver

carcass out there one time. It was a big one, about forty-five pounds. So we

stuck it up on a tree and figured that a wildcat would start eating on it, and

then we’d set some traps and catch it. Well, we came back a half a week later—it

was gone—the whole thing. The tracks were huge. They looked just like a dog’s

but it wasn’t. It was a cat. It dragged the beaver away without dragging the

tail, so that was a pretty big cat. And it made it up over a log with no

problem. They claim that there weren’t any cats in here, but there were. They

would just move in and out of the area. That was in the ‘60s around ‘65–‘67.

An old photograph from Spruce in the mid 1940’s. During this time deer were still rare in the woods, and for someone to bag two mid size bucks was a feat indeed. Photo courtesy Dorie Powers

Squirrel Hunting; Rather Be Fishing

Hazel Phillips recalls growing up during the 1920’s in a family that did not let the girls hunt, despite her strong interest in it:

My brothers wouldn’t take me hunting. They would take me fishing, but they wouldn’t take me hunting. They had one .22 that they had bought, and when they went hunting, one would shoot one squirrel and then he would hand it to the other brother. They would hunt until he shot that squirrel, but they never would let me hunt. And then, after I got married, the boys got Jim into hunting, and he loved to hunt. We didn’t have any children.

He came home one day—he got off of work—and he said, “Come on, go hunting with me.”

And I said, “No. I have ironing, and I don’t want to go hunting.”

He said, “Come, go with me.”

I said, “No, I don’t want to.”

He said, “If you don’t go then I’ll go back to work.”

Well, he didn’t drink or chase around or anything, and I figured he has to have some sort of recreation. So I said OK, and I went. We only had a .22. We didn’t have money to get another gun. Finally he got enough money to buy a shotgun, and he gave me the .22. And then I started hunting with him.

I remember one time we were up there along the river—he’d got the afternoon off—and we’d come back to the car. We’d always went separate ways because I knew the forest like he did, and we always figured some place in the forest to meet and have lunch together.

He said, “How many squirrels did you get?”

I said, “Well, I got my limit, how many did you get?”

He had had two less than I did, and he said, “Well, I have a notion to wallop you right here in the field because of your squirrels.” (Laughs)

We hunted a lot. Every Saturday we hunted, sometimes in the evening.

Another woman who did not get the chance to try hunting until she was an adult, Lillie Mae Isner, talks about her experiences with the sport:

Ohh, I used to go with my father-in-law, just to be going. But I shot that old shotgun, and it kicked my shoulder. See, I’d never gone hunting before. That was the first year I’d been up here, and he’d go hunting. He was a good shot at that age too, oh boy, and I’d go with him. I shot that old shotgun, and I thought my shoulder was going to leave.

I’d go, but I didn’t like to shoot. They’d

say, you didn’t hold it tight enough, you know?

I’d go, but I didn’t like to shoot. They’d

say, you didn’t hold it tight enough, you know?

And I said, “Naw, I’d rather hold a fishin’ pole.”

Yes sir. All them years Howard’s dad never got but one deer—and it went across the river—but he didn’t go to go get it. Howard only got one deer in his lifetime, but it seems like there are more now than there were.

They mostly hunted squirrels. They’d hunt squirrels, and I’d cook ‘em and help clean up. Stuff like that I could do—killing chickens and helping kill hogs and stuff like that—I could do. But Howard, my husband, he could shoot them. That wouldn’t phase him, but to go get them, he wouldn’t. After the odor goes down, he could deal with it. But to gut them, he couldn’t do it. He’d get sick as a dog. Yes sir.

Trappin’: Leo Weese (drinking) and Marshall Reed pause for a moment on a

hunting/trapping excursion in the Shavers Fork.

This photo is from the 1950s.

Photo Courtesy Leo Weese

Turkeys, Deer, Pheasants

Bert Weese took his wife hunting. He tells about the old days and hunting around Spruce in the early decades of the twentieth century:

Turkeys, deer, pheasants. I killed two deer: one while at Spruce, one here after I moved out. Whenever you wanted a mess of squirrels, you had to drop down on Cass road or drop down to Valley River a little ways down into the hardwoods, and I’d kill me a mess of squirrels. We had some restrictions: during breeding time, when the doe is carrying the fawn and when the fawn is little.

There was a period there of three or four months through the summer that you didn’t have no meat. There wasn’t no electric up there and no refrigeration, so it would spoil. And you wouldn’t want to kill a doe that was going to have a fawn. Wouldn’t hunt turkeys either when they had little ones. And the timber was big. That’s before they cut it the second time. Then they put a mill in and a boarding house—put one up at the Cheat River—and they put one up at the Big Cut. These were logging camps.

I’d go hunting and go by the Cheat River up there; it would be about noon. I’d sit down at the big long table, and they had pies, cakes, two or three different kinds of meat and potatoes, everything you could think of. Old Shays would bring it up from Spruce. They had a cook. Sager was one of the camp cooks. I can’t think of it now, it’s been so long. There were four camps when I was up there.

I would go up to the top of the hill at Old

Spruce, maybe kill a turkey or some squirrels or something and go to work about

2:30. I’d hunt until about noon. Then I’d drop down over onto the Shay track

with empties. They’d slow down and pick me up. I’d maybe run to the top of the

hill or fire to the top of the hill for the fireman. Then they’d slow down, let

me off, and I’d have time to get ready and go to work. That’s all me and the

Mrs.—her name is Edna—did was hunt and fish. I suppose she’s killed fifteen deer

in her time. And I suppose she’s killed maybe twenty–twenty-five turkeys.

Pelts: Beaver skins trapped on the headwaters of Shavers Fork, where Snowshoe is now. These and more were all from one winter. Pictured are 33 pelts. In the late 50’s he would get 35 dollars a pelt. Pictured are Harley Watson, Marshall Reed, Leo Weese, Owen Smith. Photo Courtesy Leo Weese.

Abundant Deer and Strangers in the Woods

As time went on, hunting pressure increased as the number of people able to travel to the wilderness grew.

Kenny Watson, a current resident of Stalnaker Run north of Elkins, talks a bit about the change:

When we used to go over there in the early ‘60s, everybody that you saw, you knew. There was only a certain group of people that hunted that river at that time. You’d see somebody’s vehicle, “Oh that’s so and so, parked there.” You’d stop and leave a note on their vehicle. You know?

Everybody knew everybody. If you saw somebody in the woods, you can bet you can just go to them because you knew that person. But now, it’s not like that anymore. There’s a lot of people down there, and it’s sad because there’s a lot of riffraff.

Hunting pressure has also increased simply because the deer population of the surrounding woods has exploded. The population has grown to such an extreme that if someone spends the deer season in the woods, he or she is almost certain to get a shot at some deer. This was not always the case. In the 1920s, the state’s population of deer neared extinction. Nonetheless, this didn’t stop some people from hunting.

Shawn Mullenex recalls:

My granddaddy used to tell me: “Back in the ‘30s,” he said, “there was no deer back in the valleys. You had to come up to the mountain to kill a deer. They were far and few between.” He said, “If you found a track, you’d better get on it and stay on it until you killed it.” He said the deer just weren’t like the way they are now.

The increase in people roaming the hills also means an increase in accidents. Hazel Phillips and her sister Grace Gainer relate this tragic tale as a reminder to make sure you know exactly what you are shooting at, before you take the shot:

Hazel: We deer hunted. My brother come in one deer season, and we all made plans to go up there along Shavers to deer hunt. There was about six of us. We were going up into this field and all at once, this one man had his arm like this, and then my brother was next. Someone had spoken to Jim, and he stepped back. This man stepped up in his place about twenty-five feet back, and we hadn’t gone twenty-five feet when some kid cut down on us with a shotgun with a talcum ball.

It went through the first man’s arm; it missed my brother and went back to where Jim had been about twenty-five feet back. Hit him right here (indicating her forehead). Killed him. He just dropped to the ground. It was a terrible experience.

Matt: Did they catch the kid who did it?

Hazel: Yeah, he just wept. He screamed. He was only sixteen years old—the first time he’d ever been hunting. He came down running and yelling, “That’s my deer. That’s my deer! I got him. I shot him.”

My brother said, “Sonny you didn’t shoot a deer. You shot a man.” And he just wept. He just cried. So that was a terrible experience. I quit deer hunting after that.

Grace: Our brother did too. They never went hunting after that. They stayed with me that night, and I got up the next morning—there was four of them—and I made buckwheat cakes and sausage. They had the best big breakfast. They just acted the fool and just carried on: who was gonna get a deer . . . and boy it put a damper. I love to fish, but I don’t like to hunt.

Hazel: I tell you, it is dangerous. Some people think they have to have a deer and they just shoot at anything.

Cheat Mountain Club

Nestled in the woods near Cheat Bridge

stands one of the oldest and best-built manmade structures on the Shavers

Fork. Its name has

changed through the ages, but Cheat Mountain Club seems

to be

one of the longer standing names.

Carl Frischkorn regales

us with history of the club:

one of the longer standing names.

Carl Frischkorn regales

us with history of the club:

The club was built in 1887 as the Cheat Mountain Sportsman’s Association. A series of lumber companies, which became Westvaco, leased the land on which the clubhouse was built. The people who originally founded the club were Carnegies, Fricks, Mellons, and Babcocks—a bunch of the big early industrialists from Pittsburgh. They built the club as a sportsman’s retreat. It was the biggest hunting lease east of the Rocky Mountains.

I guess they came here originally as a result of the Civil War, which really opened up this land and exposed it for its economic opportunity. The club was built as a result of the industrial development. By the turn of the century, they had cut so much timber that it ruined the fishery. So the Pittsburgh group began to dwindle at that time.

The Cheat Mountain Club in 1935. Photo courtesy Monongahela National Forest.

They were replaced by a couple of transitional ownerships. The Cheat Mountain Club then merged with something called the Allegheny Mountain Sportsmen’s Club. They were going to merge to make a huge hunting preserve. I think what happened was the Cheat Mountain Club ran into financial difficulty. It lost its “umph.” The club transitioned sometime in the teens to be jointly run with the Allegheny Club. But that must not have worked because in the twenties a group from Fairmont and Clarksburg became the dominant members. And that was a transition to the more local ownership/membership.

From there it was operated as a really nice bed and breakfast, and still can be occasionally rented out weekly for private use. The club’s history includes many famous names, including a trip made by Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, Harvey Firestone, and John Burroughs, all of whom used to go on back-road camping trips during the beginning of the twentieth century. The Cheat Mountain Club logbook entries that appear throughout the book are full of glimpses of the wilds of Cheat Mountain and the abundance of brook trout in the Shavers Fork.

From the Cheat Mountain Club logbook. Photo by Matthew Branch.