Chapter 8

“It’s a

classic West Virginia hunting or fishing camp: somebody put a trailer out and

before you know it, somebody put an addition on it. Before you know it somebody

put a deck on it and that’s about when we arrived.”—Al

Krueger

Outdoors:

Love of the

Wilderness

Camping

has always been a popular pastime on the Shavers Fork. The wilderness calls for

roughing it, leaving the comforts and confusion of civilization behind for a

while. Native Americans had few permanent settlements in the watershed but many

hunting camps. Doubtless even then the watershed was known as a wilderness.

While camping has become more popular since the ‘60s, there were plenty of

people with stories about camping back in the old days.

Camping

has always been a popular pastime on the Shavers Fork. The wilderness calls for

roughing it, leaving the comforts and confusion of civilization behind for a

while. Native Americans had few permanent settlements in the watershed but many

hunting camps. Doubtless even then the watershed was known as a wilderness.

While camping has become more popular since the ‘60s, there were plenty of

people with stories about camping back in the old days.

An adventurous Forest Service employee snowshoeing just below High Falls of

Cheat in January of 1948. Photo Courtesy Monongahela National Forest

Fluffo and Frozen Apples

Henry Nefflen has

a string of stories from his childhood in the 1950’s:

There was another time

that three of us went down, and we were going to trap. It was Jim Phillips, Bill

Boyles, and me. Back then we used to have a week off for Thanksgiving. At Nail

Run—that’s about halfway between here and Parsons—there’s an old schoolhouse

that a father of a friend owned. My parents insisted that I stay home for

Thanksgiving dinner, and my Mom sent in a pumpkin pie with me. When I went in it

was dark, and it started to snow, real big flakes.

My Dad brought us out.

One guy was already there, and I had traps, a gun, hip boots, clothing. It was

snowing like hell. Those SUVs weren’t all over the country back then either.

Hardly anyone had four-wheel drive. If someone wanted to go somewhere when it

was snowing they put chains on their wheels. A four-wheel drive vehicle was a

rarity. The power companies had them, and maybe the state had a couple. Dad had

a Pontiac station wagon, and he was worried about getting out of there.

Dad dropped us off, and

all the sudden we realized that all we had for that whole week was that pumpkin

pie I brought. Nobody else had brought any food. I was thinking that Jim had

food; he thought that we had food. Bill didn’t bring anything. And nobody was

coming after us for about a week. It snowed about two–three feet so there was no

way anybody was going to come after us.

We figured that we would set out

our traps and we would eat what we could catch. So we got all our traps set. We

set them down by the river. We thought we knew what we were doing but we were

novices and we didn’t really know what we were doing. The river came up—I mean

way up—and we lost all of our traps.

We didn’t have nothing.

We had a .22 and a handful of shells. We figured that if we shot a deer, no one

would get too mad at us if we took one out to keep us from starving to death.

But the snow was too deep for anything to stir. We did manage to kill one red

squirrel.

We found an old apple tree, and we

dug apples out of the snow. Those apples were rock hard. I mean rock hard. There

was a can of Fluffo. It was like Crisco but it was yellow. It was shortening. So

we had a can of Fluffo

and we found a box of pancake mix. So we had Fluffo,

pancakes, and apples because we ate that pie right away. So, for like four days

that was all we had to eat. Apples. Fried apples—we had to thaw them out—and we

would make apple pancakes. I remember spreading that Fluffo on the pancakes like

butter to make it taste better. I just about forgot about that trip . . . I was

probably sixteen years old. It was around 1960, forty-three years ago.

that Fluffo on the pancakes like

butter to make it taste better. I just about forgot about that trip . . . I was

probably sixteen years old. It was around 1960, forty-three years ago.

About the fourth or fifth day the

weather straightened up a bit and we found a house that wasn’t very far away. We

went up to the house and knocked on the door, and this kindly old woman came

out. We had some money between the three of us, and we offered to buy some milk,

because we figured milk and eggs would be the best thing in the world then. She

asked us why, and we explained everything to her. And she wouldn’t have none of

it. She took us in, and she fed us. I don’t know what it was, but boy, it was

one the best meals of my life. She insisted that we eat and she just poured the

food on.

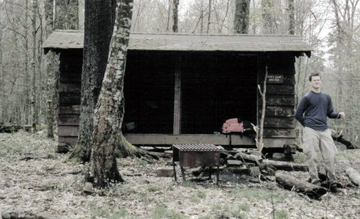

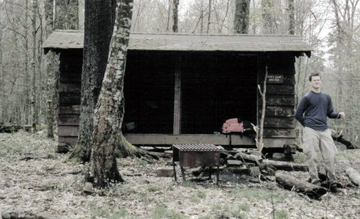

John’s Camp Shelter: One of the shelters along

the Allegheny trail. Here the trail skirts the Back Allegheny Mountain near

Gaudineer Scenic area. Pictured is Justin Hargeshiemer a hiker from Alaska,

Justin says of the area, "This shelter was great, although

we ended up sleeping farther down the trail. It was located about four miles

from where we started, and at that point we just weren't ready to call it quits

for the day. There was a muddy sort of gully nearby, which made me think that

the shelter had originally been positioned in order to have a water source, but

it was mostly dry as we passed that day. It was plenty adequate for a lunch

break however..."

Photo courtesy Matthew Branch

Camping

on Little Black Fork

Henry continues:

Another time, Weese and

I went camping down here at Little Black Fork. It’s down here about four–five

miles. There are two streams down there, and they used to be real good trout

streams. They stocked them and there wasn’t near the pressure that there is now.

Like I said, you could drive up and down this river all day and not see another

soul. Went down on our bikes. We went way up there, and we camped.

Weese—he was a piece of

work—in high school he made the All American Team. He

was tenacious as hell,

but not very big so he

only got one scholarship out of it. He was an

animal but he was scared to death of bugs. We

were

sitting there, and we had a campfire—a June bug landed on his toe—and he lost

it. We had a .22, and he starts shooting at the June bug. He starts shooting

everywhere. He shoots a hole in the frying pan—so he disables the frying pan—and

we were supposed to be up there about a week with no way of cooking anything.

were

sitting there, and we had a campfire—a June bug landed on his toe—and he lost

it. We had a .22, and he starts shooting at the June bug. He starts shooting

everywhere. He shoots a hole in the frying pan—so he disables the frying pan—and

we were supposed to be up there about a week with no way of cooking anything.

There still is a lot of empty

space up on the Shavers watershed. You could probably still spend a week up

there and not see another soul. We used to go up near Linan. There would be

three families of us, and we would make a big camp. We’d bring the kids and the

grandparents. And whoever had to work would go to work—that camp would be our

home for a while. People

still do it [camp out] some but

its not done as much as they used to. Now people have campers and whatnot. It’s

different now.

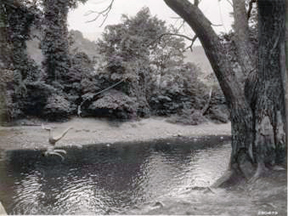

A campsite in the Monongahela National Forest,

1960’s. Photo courtesy Monongahela National Forest.

Walking

Off the Mountain

Boone Hall, who

operates a small campground in Bowden, has a story a lot more common among

campers today, especially those in the Bowden and Bemis area:

I originally started

camping up in Bear Haven. We just cleared off a spot and put a tent up. That was

‘57–‘58. Then we started camping at Stuarts Park. Then I cleared off a place

here and started camping. I hooked up the electric myself and did everything myself—well, me and my wife.

Now we’ve

probably got about twenty campers down there.

It’s just a bunch of friends. I retired a year and a half ago, and I’ve been up

here every week.

I hooked up the electric myself and did everything myself—well, me and my wife.

Now we’ve

probably got about twenty campers down there.

It’s just a bunch of friends. I retired a year and a half ago, and I’ve been up

here every week.

The first time I walked off the

mountain—I was about twenty years old—they told me it was an old Indian trail. I

walked down there, and it was rocks, cliffs, briars, brush. I never did find

that trail. I come down off that mountain, and a deer jumped—it scared me—I was

ready to shoot at anything. I was scared to death. You can’t get lost walking

off the mountain, but it takes about three hours to walk off the mountain.

That’s called Bickles Knob. Have you been up there yet? You should go up it. You

could do a lot up there. I can take you any time. We’ll go out . . . evening

when the sun goes down, it is the prettiest thing you have ever seen.

-

Bowden: An old photo of the

town of Bowden. Now much of it has changed, and is largely covered by

campgrounds.

Note the cleared pastures on the mountainside.

Photo courtesy Keith Metheny from his

grandfather, Clair Metheny.

Fireworks and Cavers

Chuck Hayhurst shares a

few humorous tales about his experiences camping, first at Alpine Shores, and

later at Revelle’s River Retreat, also in Bowden:

One night

up there—the 30th of May, Memorial Day—we always bought fireworks . . . No, it

was the 4th of July . . . We always bought fireworks. We had a friend from

Pittsburgh, and he always brought fireworks. We all pitched in and got some

fireworks. Every night at dark we put them things off. The people that have a

house about the campground there—Lorraine’s oldest son Tom, you’ve probably met

him—him and his two boys were up there on the porch. They were shooting

fireworks down at us, and we were shooting fireworks right back up at them. Kids

were pitching horseshoes. We had lights on down there, and we were having a big

time. And here come the state police, man and a woman, flying low!

The whole campground was

full of kids, and so the guys took off with the fireworks. One guy went this way

with the fireworks; another guy went the other way. So they came up and asked us

if we knew anything about it. We didn’t, and they started going around and

asking other folks if they knew anything about it. No one else knew anything

about it either.

We

asked them, “How did you know that we was doing this?”

We

asked them, “How did you know that we was doing this?”

They said, “We was over

here, and we had stopped a car and was giving a citation.” But I knew that it

was somebody else had turned us in.

Anyway, they said, “If

we have to come back over here tonight, we’re gonna arrest each and every one of

you.”

We said, “What for?

We’re setting around a campfire drinking coffee.”

He said, “We’re gonna

get ya for drinking.”

I said, “How are you

gonna get anybody for drinking?”

I said, “Look it here:

everybody around here has a cup of coffee in their hand.”

And he hemmed and hawed

around that. He said, “We don’t know anything about that.” They had no sooner

left the driveway than Tommy started shooting fireworks at us, and we were

firing them back.

An evening around the

fire at Cheat River Campground, Faulkner.

Photo courtesy Shavers Fork Coalition.

Do

you remember when the spelunkers used to come up to Alpine Shores? They got a

bunch of spelunkers—that’s cave dwellers—they used to rent the whole campground,

and we were permanent up there. They had a big tent up right at the entrance. We

had to wear name plates before we could even get in our own campground. There

was doctors and lawyers, you name it. And they just let it all hang out. They

had the damnedest time you ever seen anybody have in your whole life. For a

whole weekend!

I got mad, and whenever

I couldn’t get to my camper because they had everything blocked off, I started

cutting ropes and everything else. There was a tent line going into my camper, and there was tents up in my yard. I went up and started raising hell

with the owner, Mrs. Burke.

camper, and there was tents up in my yard. I went up and started raising hell

with the owner, Mrs. Burke.

And she said, “No, No,

No, you gotta stay. You’ve never seen anything like this in your life!” Buddy,

we’ve NEVER seen anything like that in our lives!

This old boy here, he had this dog

. . . and, oh man, that dog . . . if he ate steak; the dog ate steak. One

morning he threw that dog some ham down in his plate on the ground. The dog just

cocked his leg and peed on it.

I said, “See what that

dog thinks of that damn ham? That dog wants steak. He don’t want ham!”

The cavers have since purchased

land for their annual gatherings but Chuck will always remember them.

Big Cat Tales

Stanley Woodell

wrote about his grandfather camping on top of Cheat Mountain sometime around the

turn of the twentieth century, before the railroad came in. What the wilderness

looked like then, we can only imagine:

My

granddad Amos Wooddell, Grant Higgins, Hanson Lindsay and my Dad were camping at

a small clearing about one half mile from what later was Old Spruce. They

cleaned their fish and threw the heads in the laurel by a spring. Just before

dark, Grant Higgins went to the spring for water and heard some animal growl.

The men lay down on some pine limbs to sleep. My Dad was next to the fire, and

Grant Higgins was on the outside.

After dark, Grant felt

something on his chest. He thought it was my Dad’s arm but when he felt warm air

in his face he opened his eyes to see a panther’s face. He screamed and rolled

across my Dad into the fire. They all jumped up and saw the long tailed panther

run into the woods. They built a big fire and sat around it the rest of the

night. The panther came back and sat on a log nearby and they could hear it

patting its tail on the log. They threw firewood at it but it

stayed until almost daylight and

it screamed as it went up the mountainside toward what is now called Bald Knob

[now part of Cass Scenic Railroad State Park].

While officially mountain lions

don’t exist in West Virginia, almost everyone had a story about seeing a big

cat. Perhaps the panthers have not yet heard that they are extinct.

Jean Wagener

recalls a hair-raising story:

My connection to Shavers

Fork began when I married Jerry Wagener in 1961. Jerry’s aunt, Mineta Anne

(Wagener) Auville, lived with her husband Raymond “Doc” Auville, below Two Lick

on the east side of the river from the late 40s until the late 50s. The

property is often referred to as “the old Auville place,” though their home has

been gone for many, many years.

But this was before our

cabin was built so this would have been probably ‘62. We were tent camping where

Jerry’s aunt’s house used to have been. Jerry’s brother was in a hammock up

above the road, en route to where our cabin is now. My parents were there and

Jerry and I. It was about 4:30 in the morning—it was early fall or late summer—I

heard the most horrible noise I have ever heard or ever want to hear in my life.

It was an absolutely blood-curdling scream—like a woman screaming.

I really did think that

if walked just a few feet to the riverbank we would see a woman chopped up into

a million pieces. We emerged—we were sleeping in the back of a station wagon,

and my Dad was coming out of the tent—the first thing that we thought of was

Jerry’s brother. Although we thought that the sound came from the river, we

worried about him sleeping up in the woods. He had slept through it. He hadn’t

even heard it.

We weren’t familiar with that blood-curdling

scream but we understand that with the mountain lion that occurs in either

mating or a kill. People know that. We didn’t see anything. It could have been

across the river but it was so loud! It makes my blood run cold just to talk

about it now. I never thought that there would be anything like that. It was

just terrible. In that same era, we found some pretty big prints that we thought

were cat prints. We took molds of them and brought them in. You never know.

Panther on Red Run

Jim White

tells the following story from not too long ago:

The only panther I ever knew or heard . . .

I’ve never heard a panther, I don’t think. My wife was in the hospital, and I

was working at the observatory. She had to have an operation. She was over in

the hospital. That must have been in 1968 or ‘69.

I was going over one

evening to see my wife. There is an area over on top of the mountain as you go

over Cheat Mountain from Durbin to Huttonsville. There is a run on top of the

mountain called Red Run. They call it that. It’s beyond Cheat Bridge. You can

see it there if you look for it. I tell you this before we get into the panther

tale.

The water that was up on

Cheat Mountain was like this: when that water got up, in any kind of a flood

stage, instead of turning muddy and milky like it did down here, it turned a

dark red. The superintendent here, they were having a debate over what was

turning the water red, so he wrote an article to the paper—I don’t know if it

was the one [newspaper] in Marlinton or the one in Charleston. But he came up

with the best explanation.

I guess the real reason

is that red spruce—the roots of it are real red—and that’s where it gets it name

from. The spruce tree isn’t red, and the timber isn’t red. The reason they call

it that is because of the roots. The roots—when you dig down to them, those

things have a red bark on them. So when the waters wash through those roots,

they turn the water red. That’s how Red Run got its name. If you look at that

run in the summertime when you can see it real good, or any time when there

isn’t snow on it or ice on it, you can see it real good. So, that’s how that got

its name.

Anyway, in that area

there is a big curve. There was a big gradual curve in the road—and that is

before you start to climb a little elevation to climb another mountaintop. You

are climbing two mountains: one on this side of Shavers Fork and one on the

other side. One is Back Allegheny and the other is either Cheat Mountain or

Shavers Mountain. But in that big curve—I was going there at night, it was a

while yet before dark—and something jumped in the road. At first I thought that

it was a huge dog. It was big. But it didn’t go across the road, it went and it

crouched just like a cat. It looked like a big cat. And then it jumped right

back into that wooded area. The two things that I remember about it is that it

jumped like a cat, just like a cat, and that it had a big long tail after it.

And it was the color of a panther.

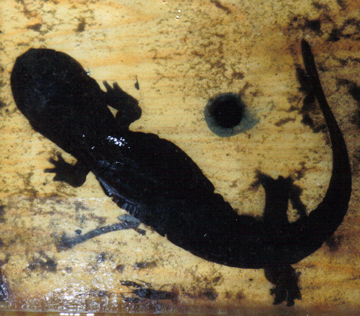

Waterdogs,

Hellbenders

Not all animals on

Shavers Fork are as fearsome as panthers.

Henry Nefflen

describes one of the creatures that inhabits the watershed:

A

waterdog is an amphibian; it’s not a lizard. It looks like a baby alligator.

They get pretty long, like two feet. Someone caught one fishing the other day

and they kept them for a bit. They are all over the Appalachians. I’ve seen them

up to about twenty-eight inches long. Most folks that catch them kill them. I

used to too because I thought they killed fish, but they don’t.

A

waterdog is an amphibian; it’s not a lizard. It looks like a baby alligator.

They get pretty long, like two feet. Someone caught one fishing the other day

and they kept them for a bit. They are all over the Appalachians. I’ve seen them

up to about twenty-eight inches long. Most folks that catch them kill them. I

used to too because I thought they killed fish, but they don’t.

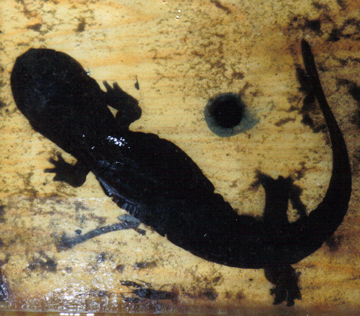

MudDog: Henry Nefflen says, “I’ve seen some that are

huge. Most of them are like this, and if you pick them up, it’s just like

picking up Jell-o. You see that crawdad? (bottom center) That wasn’t a little

crawdad, and that next to it is a full sized night-crawler. And like I said,

coons love ‘em, if you’re ever out along the river, particularly in the summer

and you come to a flat rock, and there’s a skull and a piece of backbone or

vertebra, that’s the remains of a waterdog. They’ll leave the head and the

backbone, that’s all you’ll ever find.”

Photo courtesy of

Henry Nefflen

A guy caught one, back

when we had the store, and he brought it in. We put it in a fish tank, and no

sooner had we gotten it, the DNR [Department of Natural Resources] came in like

three hours later, and they wanted us to turn it loose. He explained why and

gave us a lot of information. He said the one that we had, which was twenty-two,

twenty-three inches long and was about this big [diameter of soda can]. He said

that they live twenty-five–thirty years. They don’t know how long. They rarely

travel more than fifty feet from where they were born. They are just, if you

pick one up, it feels like you are picking up a lump of jelly.

They have lungs but the oxygen

exchange goes through their skin. ‘Coons love ‘em. The DNR guy typed a bunch of

it up, and we put some information up. We had people coming in for days on end

to look at that thing. I told the DNR guys that I wanted to show them to the

people. They thought it was a good idea, and they let us keep it for a bit.

After a while, we turned it back loose in the river. I’ve seen a bunch of them.

If you’re ever up the river, and you find a flat rock with a skull and a

backbone on it, that’s the remains of a waterdog. That’s all you’ll ever find.

Steve Lambert,

who grew up in Parsons, recalls these waterdogs, also called hellbenders:

Under

the town bridge in Parsons—that’s still part of Shavers Fork—I don’t know what

they are, the name or scientific name or anything about them, but us kids called

them waterdogs. They were great big lizards, about one and a half feet long.

You’d find them in the river hiding around the rocks. They would bite you, so we

would catch them by the tail and build a dam out of rock underneath the bridge

and keep them there. They’d eventually get out, I guess. I don’t hear kids talk

about them today. They wouldn’t make very good pets. They were ugly and would

latch on to you.

When I was a boy, we did spend an

awful lot of time on the river playing and jumping around. I lived with my great

grandmother in Parsons. If you went swimming, you’d better be dry before you

went home. She didn’t want me in the river. She never learned to swim herself

and was afraid I would drown. We did a lot of swimming but I have to tell you, I

made sure I was dry.

Bears

and Bark

Leo Weese tells a

strange story from the headwaters of the river:

We

went up there one time—come around the bend from Slide Run [now on Snowshoe

property] in the head of the river—and then you go up a little ways and come

around the bend, and it opens up to a big basement. We came around a bend, and

the whole side of one hill was nothing but red. We got up there to see what in

the world it was. They had cut the timber, and little pine trees were growing

back in, but the pine logs were still lying there. Bear had torn that entire

side of the mountain there. I don’t know how many bears there were but they had

torn up the entire side of the mountain! They were eating the grubs inside the

bark. The whole side of that mountain was red! Shoot, there had to have been

ten, fifteen, twenty bears in order to tear up that whole thing.

We

went up there one time—come around the bend from Slide Run [now on Snowshoe

property] in the head of the river—and then you go up a little ways and come

around the bend, and it opens up to a big basement. We came around a bend, and

the whole side of one hill was nothing but red. We got up there to see what in

the world it was. They had cut the timber, and little pine trees were growing

back in, but the pine logs were still lying there. Bear had torn that entire

side of the mountain there. I don’t know how many bears there were but they had

torn up the entire side of the mountain! They were eating the grubs inside the

bark. The whole side of that mountain was red! Shoot, there had to have been

ten, fifteen, twenty bears in order to tear up that whole thing.

With the bear population on the

rise, more and more incidents involving bears occur.

Virgil Broughton

relates the following story:

I got bear-bit three

years ago up there. It was pure accident. I go up there [near the townsite of

Spruce] a lot by myself because I know that country. I was in a tent, and they

was real hungry. A big old bear and her cub smelled those rotten apples I’d put

out and came in under my tent. They feed out of those dumpsters at Snowshoe and

Silver Creek [ski resorts] so now they’re used to people. She came in, and I get

up trying to shoo her out because I don’t want her in there while I’m sleeping.

She got nasty about it. She don’t want to leave. I didn’t aim to kick her but I

kicked a little bit and got her in the side. And she turned and snapped and got

me in the calf of the leg. But as quick as she did that, she got the scent of

the blood, and boy she went through the tent. She left in a hurry, she and her

cub.

Jim Bazzle

recalls one instance where a bear showed up unexpectedly at his campground:

A while back we had a

bear cross the campground here. He came down off the mountain, crossed 33 and

the campground and went up the other mountain. That caused a commotion. There

was an elderly couple—I can’t remember their names but they were regulars—and

the wife said she heard a noise. The husband got up and saw a good-sized black

bear rummaging through their things.

He had a dry sense of

humor and said, “Oh, its nothing but a big black bear out there.”

She says, “Oh come on.”

And she opens the door and, of course, slams the door and screams. The bear got

scared and ran off. The stories that circulated from that were just great.

Tent camping

in the National Forest. Photo courtesy Monongahela National Forest.

Kayaking in Winter

Jim Snyder

wrote about one of his amazing journeys down the Shavers Fork in a kayak during

the wintertime. The trip takes two days and the camping seems extreme:

Iceman has claws a half inch long of pure crystalline water but he’s not really

dangerous. Slushpuppy’s paws are also armored in ice, on the outside at least.

He’s pretty harmless too. He’s been mesmerized by the “phhhht, phhht, phhhht”

sound of the endless slush balls that have been grazing past his hull for hours.

The slush appeared overnight. It was a very cold night. These two characters

have nearly returned to civilization.

The

first cabin they encounter has a young couple walking their dog in the brisk

sunny snow. “Did you camp overnight up there?” They can’t help but wonder.

“That’s pretty brave in this weather,” they concede.

Slushpuppy

mumbles that he read something about sunny beaches in the brochure. “That’s

after March first. You should have read the fine print,” he’s informed.

Still dazzled,

Slushpuppy admits, “It was beautiful anyway.” They slip back into the

persuasions of the current.

The crystal

clear water seemed to be calling them on. “Don’t mind the howling wind,” it

said. “Come ride through the beauty. You won’t have to say a word. Just witness

what is offered.” The howling wind was a factor but they didn’t mind. Their

inner warmth pounded out through their face as it had for the last twenty-four

hours. The searching wind sucked it away hungrily. No harm done. There’s more

where that came from.

The

wind first said hello in no uncertain terms at the highest put-in east of the

Black Hills of South Dakota—some 3,800 feet above sea level in the abandoned

logging town of Spruce, West Virginia, on the highest reach of the Shavers Fork

of the Cheat River. The wind owns this sunny spot in the woods now. It sweeps in

and cleans it regularly, looking for strange characters like Iceman and

Slushpuppy.

They presented

themselves to the elements by jumping from the Salamander, a sightseeing

excursion train, which conveniently supplied their entire shuttle. Their

vehicles would be waiting at the take-out tomorrow. About thirty senior citizens

were on the train: now peering from the windows as if watching a car wreck. They

were concerned but unable to voice any cautious tones. It was clear there was no

stopping these characters.

They pulled their boats off and slipped quietly away toward the diminutive

stream amidst swirls of glistening snow tornadoes. They were on their way, alone

together into the cold. The boats were maybe ninety pounds each and a bit

sluggish. But the river slid by, undemanding for the most part. A small rock

here; a leaning tree there. It was just enough to keep you busy.

In

no time at all, signs of Spruce were gone and all that remained was the gin

clear water and the curious wind working its way through a forest trying

to rediscover itself. Once a cathedral of towering spruce trees it was now a

recovering wilderness with a large deciduous population featuring spunky birch

trees as a predominant species.

There was occasional conversation, but Iceman and Slushpuppy would consistently

disappear, becoming only silent hulls blended with water and rocks. It had to be

cold. Their boats and hand coverings were shielded in ice within the first few

minutes of the trip. Temperatures around twenty and ten to fifteen mile per hour

winds will do that to you. Your boat, paddle, hands, skirt, and helmet all

acquire a sheen of pure ice. It’s exceedingly cool.

After a while it was time to search out a campsite so there would be time to

start dinner before dark. From his boat, Slushpuppy identified a flat area near

a hillside and in among the trees where the wind would have a harder time

finding them. He got out of his boat to check more closely and walked to the

actual spot. When he got there he could see the ground was really quite soggy

and wet—unusable. It had rained the day before, affording them the water to

travel on, but now the snow iced everything over. He went to call to Iceman to

tell him he might want to stay in his boat and save himself the trouble but it

was too late. He was already out of his boat and coming to see the situation for

himself.

After a few minutes of searching, it was clear there were no good spots at this

landing and they would have to proceed further down the river. But a problem had

developed. In the five minutes it had taken to check the site, their

spray-skirts had frozen solid. They wouldn’t go back on the boats to seal the

water out in this condition. Slushpuppy’s hands were bleeding from the tiny cuts

the ice was giving him. They would have to proceed without the skirts on.

There’s only so much water you can get in a ninety-pound kayak, before you start

to sink.

Fortunately, they found a fine site before the beginning of the next riffle—a

great flat site, which had been used before at the mouth of the sizable “Second

Fork” of the Shavers Fork. Without much ado, they started gathering firewood in

earnest. River creatures are pretty vulnerable when out of their shells.

Within a half hour the fire was crackling and they had a sense they could

survive. More firewood and more and more and more were stacked in a high heap

near the fire. The temperatures were plummeting and the wind and snow were

really kicking up. The air temperatures were dropping fast through the teens in

the last hour or so before dark. Fire established, they made short work of

setting up a shielding tarp and a couple tents.

Slushpuppy brought three sleeping bags because he is intimidated by the cold and

didn’t want to die a cool but stupid death. Dark came on and the cold dominated.

Slushpuppy went to get three cups of water from the river to make some nice

spicy Jambalaya with chicken for dinner. The first cup poured into the aluminum

pot froze solid. The two following rendered a pile of slush. Then Slushpuppy

found that his cooking stove had a problem with cold weather. Its poor frozen

pump gasket didn’t want to work, so onto the fire with the pot.

In about twenty

minutes (collecting firewood in the meanwhile), the food was hot and ready.

Spooned into bowls, it lasted almost five minutes before the last cold spoonfuls

disappeared. Iceman brought military MRE rations as a guaranteed food backup but

they soon froze solid. He kept his water bottles close to the fire because they

were freezing so fast.

Slushpuppy had

a tiny ice cube left in his water bottle so Iceman volunteered his thawed water

to the thirsty dog. The Pupster took a sip and then poured the rest into his

water bottle to melt his ice cube. Just that fast, the entire contents turned

into slush right before their eyes. Slushpuppy was thirsty still so he kept the

bottle close to the fire and drank the remainder as slush.

The

winds picked up to where they were howling through the treetops moaning, “Who

DARES come see? Who DARES to survive my glance?”

“I think its

bedtime,” Slushpuppy conceded at a ridiculously early hour. “I’m standing two

feet from a roaring fire and can’t feel its warmth”.

So

into the cocoons and after endless fussing, it was established they were both

“toasty warm” and guaranteed to survive the night. Within minutes Iceman was

answering the wind with peaceful snores. But Slushpuppy stayed awake for hours

for some undefined reason. Maybe he was waiting to see what would happen next?

Maybe the “phhht, phhht, phhhht” of snow piling on his tent kept

his attention.

After a while, Slushpuppy woke himself with his own snoring so he had proof that

he gotten at least some sleep. In the wee hours of the night the temperatures

slipped into the single digits with wind-chill well below zero.

Early, early in the morning, at first light, Slushpuppy ventured out to see if

the coals had frozen. The fire was way out but some coals remained. A serious

high pile of small sticks was assembled and the firewater from the

malfunctioning stove was sacrificed. Soon a “no foolin’ around” fire was

happening. The business of thawing the skirts got underway. Going to the river

for coffee water, Slushpuppy noticed things had changed. A large volume of slush

was now growing from the upstream side of rocks on the bottom of the stream. The

entire streambed of Second Fork was blanketed with the gentle structure and ice

was now encroaching from both shores in an effort to connect across the calmer

sections of current. But the winds had subsided and the temperatures were rising

over 10 degrees so a warm day seemed to be on tap.

Before long the entire camp structure had receded into the kayaks and the

characters pushed of into the slush ridden waters. “Phhht, phhht, phhhht” was

the chorus of every stroke and every bit of progress with the hull. Again they

disappeared in the silence.

Deciduous mountains spiked with snow-laden evergreens etched themselves in a

corner of their memories. They became one with a cold and indifferent world

where somehow they felt they belonged. Somehow it spoke to them, “Come back when

you can. We’ll wait for you here,” whispered the elements.

Summer Swimming Holes

Shavers Fork has its swimming

holes, of course.

Zach Henderson,

founder of the Shavers Fork Coalition, tells about how he first became enchanted

with the river:

My stories are about my

first trip to the swimming hole. You know, going out with a

couple kids from the eastern U.S. A lot of the kids at Davis and Elkins College

are from New Jersey and New York--you know, Manhattan, Long Island, Philly

suburbs--and had never experienced anything like that. I grew up on the beach,

and I knew water but I didn’t

know swimming holes.

Manhattan, Long Island, Philly

suburbs--and had never experienced anything like that. I grew up on the beach,

and I knew water but I didn’t

know swimming holes.

Swimming holes were a

whole new thing to me: going to a freshwater, deep

water spot. My first trip out there--I went with a couple kids from the eastern

shore of Maryland--and at that time they had a big platform set up in the trees.

You had to climb up to the platform and swing off the rope and you got

twenty–thirty feet of air and dropped down in that hole. There were roots coming

up the bank of the river. You had to rock climb, you know, no rocks but you had

to climb up the bank.

It was a really great

experience being out there in that freshwater stream. You travel anywhere in the

state, and that’s where people gather. It’s like the beaches of West Virginia.

You go out, and you’ll see twenty people in a swimming hole. There’s a nice

diving rock down by the fish hatchery. A lot of people go to that one, but we

try to avoid the ones with too many people.

Undated photo of four girls at a swimming hole

near Bowden. Photo courtesy Monongahela National Forest.

Swimming holes are unsupervised so

sometimes people run into trouble.

Mariwyn McClain Smith, also a Parsons’ native, recalls

a close call in the 1940’s:

I remember when my mother and sister almost drowned in the Shavers Fork. Ed was

the oldest and me and then Rachel. Mom and Dad both liked to swim real well.

They would take us to Porterwood, behind the church there in Porterwood, and

swim in the river. I guess actually, Dad saved Ed one time in that area, but the

time I’m thinking about, Rachel got in a hole and couldn’t get out. Mom went in

after her, and Rachel stood on her shoulders.

I remember when my mother and sister almost drowned in the Shavers Fork. Ed was

the oldest and me and then Rachel. Mom and Dad both liked to swim real well.

They would take us to Porterwood, behind the church there in Porterwood, and

swim in the river. I guess actually, Dad saved Ed one time in that area, but the

time I’m thinking about, Rachel got in a hole and couldn’t get out. Mom went in

after her, and Rachel stood on her shoulders.

Mom was a Red Cross

lifeguard. She was a very good swimmer. Dad went in and got Mom, and a neighbor

grabbed Rachel by her pigtails and pulled her out of there. She was probably

eight or ten at the time.

We swam in the rivers

all the time. There weren’t any pools around here. And we would walk up in the

Pulp Mill Bottom to what we would call Peterson hole, which is actually still in

town—just in town—we went there frequently. We loved the river.

Rope Swing on Shavers Fork near Bowden.

Photo courtesy Monongahela National Forest.

These spots weren’t just

popular for the swimming.

Henry Nefflen

recalls his carefree high school days:

I remember when I was a little bit

older, back when you found some thrills in a beer bottle. I remember you could

come out on a weekend and all you had to do is stop—be the first one—someone

else would see ya and bring a cooler of beer. The next guy would have a guitar

or something and then someone else, and soon you’d have a party. It wouldn’t be

anything to have twenty–thirty people out at Faulkner Hole.

August 1935, Health Camp, Shavers Fork.

Photo courtesy Monongahela National Forest.

Link to

Chapter Nine

Camping

has always been a popular pastime on the Shavers Fork. The wilderness calls for

roughing it, leaving the comforts and confusion of civilization behind for a

while. Native Americans had few permanent settlements in the watershed but many

hunting camps. Doubtless even then the watershed was known as a wilderness.

While camping has become more popular since the ‘60s, there were plenty of

people with stories about camping back in the old days.

Camping

has always been a popular pastime on the Shavers Fork. The wilderness calls for

roughing it, leaving the comforts and confusion of civilization behind for a

while. Native Americans had few permanent settlements in the watershed but many

hunting camps. Doubtless even then the watershed was known as a wilderness.

While camping has become more popular since the ‘60s, there were plenty of

people with stories about camping back in the old days.

We

asked them, “How did you know that we was doing this?”

We

asked them, “How did you know that we was doing this?”  camper, and there was tents up in my yard. I went up and started raising hell

with the owner, Mrs. Burke.

camper, and there was tents up in my yard. I went up and started raising hell

with the owner, Mrs. Burke.

I remember when my mother and sister almost drowned in the Shavers Fork. Ed was

the oldest and me and then Rachel. Mom and Dad both liked to swim real well.

They would take us to Porterwood, behind the church there in Porterwood, and

swim in the river. I guess actually, Dad saved Ed one time in that area, but the

time I’m thinking about, Rachel got in a hole and couldn’t get out. Mom went in

after her, and Rachel stood on her shoulders.

I remember when my mother and sister almost drowned in the Shavers Fork. Ed was

the oldest and me and then Rachel. Mom and Dad both liked to swim real well.

They would take us to Porterwood, behind the church there in Porterwood, and

swim in the river. I guess actually, Dad saved Ed one time in that area, but the

time I’m thinking about, Rachel got in a hole and couldn’t get out. Mom went in

after her, and Rachel stood on her shoulders.