“We walked up

on top of the hill, and that morning—it was about 5 o’clock, it was daybreak—and

there was water from one side of the hill to the other. Just tops of houses

sticking out.”

—

Jim Phillips,

Parsons resident, speaks about the 1985 flood

Floods and Weather:

It Comes in a Big

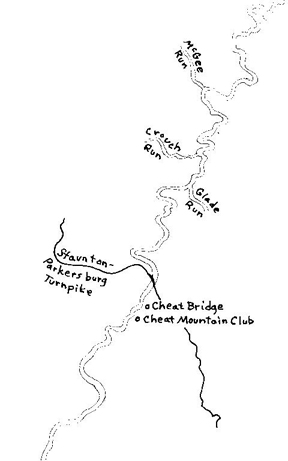

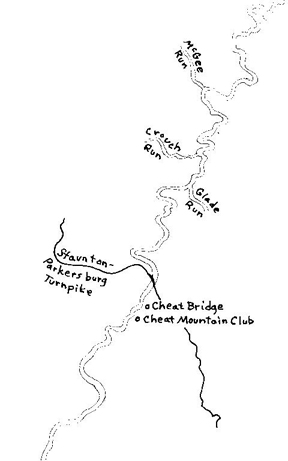

Roll West Virginia is a water wealthy state. And after Pickens in

southwestern Randolph County, Shavers Fork and Cheat Mountain are the wettest

areas in the state. Combined with the high altitude, this creates some nasty

weather atop the mountain. This high ridge had always been an obstacle in

European immigrants’ move westward. It wasn’t until the 1830s that a wagon

road—the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike—was built to cross Cheat Mountain. Modern

day U.S. Route 250 follows much of the old turnpike’s path over Cheat Mountain,

crossing the river at Cheat Bridge and descending

on the other side.

West Virginia is a water wealthy state. And after Pickens in

southwestern Randolph County, Shavers Fork and Cheat Mountain are the wettest

areas in the state. Combined with the high altitude, this creates some nasty

weather atop the mountain. This high ridge had always been an obstacle in

European immigrants’ move westward. It wasn’t until the 1830s that a wagon

road—the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike—was built to cross Cheat Mountain. Modern

day U.S. Route 250 follows much of the old turnpike’s path over Cheat Mountain,

crossing the river at Cheat Bridge and descending

on the other side.

The Trotter brothers, who were charged with transporting the mail

from Staunton to Parkersburg between 1855–1858, provide some the first written

evidence that we have of the extreme weather on the mountain. That first winter

was especially bad, and mail service suffered as a result.

After being reprimanded by their superiors,

the brothers replied with the following letter:

Mr.

Postmaster General

Washington, D.C.

Dear Sir:

If you knock the gable end of

Hell out and back it up against

Cheat Mountain and rain fire and

brimstone for forty days

and forty

nights, it won’t melt the snow enough to get your

damned mail through on time.

(signed) Trotter Brothers

by James Trotter

In the 1850s, there was no logging activity on the mountain. The

soil retained much of the precipitation, and floods weren’t such a problem.

However, snow was. Logging crews soon learned how harsh West Virginia winter can

be: 1907 was the winter that many old timers recall as being the worst.

In 1976, Forest Griffin wrote the

following in his memoir:

Granddaddy snow of them all came between 1906 and 1907. Five feet, eight inches.

Shut camps down latter part of 1906 because of snow. Started back up in 1907. A

lot of us came back to town, and some stayed at camp, the ones who didn’t have

homes.

The super came up there

and told them, “The ones that want to stay, as long as we can get here with a

couple of engines, we’ll have something to feed you. All that want to go out, go

out now.” They were off quite a good while (Pocahontas Times,

1976).

Perhaps not a coincidence,

one of the worst floods the area has ever seen occurred in 1907. Unusually heavy

rainfall combined with the recent loss of forest in the area, and the mountains

acted like a funnel, channeling water fast and furious down the Monongahela

River. This flood caused more than $100 million damage to the land around the

river and an additional $8 million more in the city of Pittsburgh. And that was

1907 dollars. A flood of those proportions today would surely be a national

disaster (C.R. McKim, 8).

Crossing

Whitewater

Harry Werner, a doctor in Bemis at

the time, recalled the 1907 flood in his memoirs, Big Doc, Little Doc:

It was 4 o’clock on an early April afternoon,

and I had dismissed the last patient from my office. As I stood a moment by the

window to listen to the roar of Cheat River, a cloud no bigger than a coat

button, appeared above the mountain ridge, casting a shadow that grew until the

narrow valley lay brooding like a tired foxhound. Spears of lightning flashed.

Thunder rattled the windows. Rain poured for ten minutes and was gone.

I had two calls to make on my way home. As I got into my raincoat,

the office door was pushed open, and Rufe Kisner came in. “Hello, Doc,” he held

out his hand.

I had known Rufe a long time. He worked in the

woods and lived on a farm near Glady. “I hope you’re not fixen to go away, Doc,”

he said. “I’d like to get you to come up to my place to see the baby. You know,

Doc, you fetched him along about Christmas.”

“Yes, I remember,” I said. “What seems to be wrong with him?”

“Well, he had the croup last night, somethin’ awful. We thought he

was better this mornin’, but he’s right smart choked up agin, and ‘pears to be

pretty hot. My woman’s afraid he might be gittin’ pneumony.”

“It’s a long walk to your place. Do you think I can see the child

and get to Glady in time to catch the train back?”

“Sure, Doc. It ain’t a fur piece the way I come down the hill an’

across the river.”

“Isn’t a boat dangerous with the water as high as it is?”

“Naw,” he said. “I didn’t have no trouble. It’s pretty swift, but

you’ll be safe as if you was in the Lord’s vest pocket. You don’t need to worry

none about gittin’ back neither. I’ll fetch you.”

As the calls that I had expected to make on my

way home were not urgent, I could make them as well in the evening, I told Rufe

I would go with him to see his baby. The rain had stopped, momentarily. We

walked to the river where Rufe had tied his boat to a tree. When I saw the swift

whitewater, I was about to change my mind. But I thought of the sick child and

remembered that Rufe had made the crossing once. His confidence jacked up my

courage.

Rufe stowed my medicine case in the bow of the boat, untied the

rope, and yelled, “Jump in, Doc, I can’t hold her agin this current.”

I looked at the raging water. Only a few days

ago it had murmured under a mask of ice. Now it was a twisting, swirling

challenge. It was thick with pilfered woods loam, yellow clay, broken branches.

With a prayer in my heart for Rufe’s guardian angel not to desert him now, I

stepped into the small rowboat. Rufe jumped in and grabbed the oars. The current

snatched our craft, and we were swept along at a giddy rate of speed.

Rufe yelled, “Sit tight. Don’t move!”

“I’m too scared to move!” I shouted back.

We barely missed a huge boulder that would have crushed the boat

like an eggshell. Rufe rowed hard upstream, using all his strength and skill to

keep us from being smashed against the rocks.

“Think we’ll make it?” I called to him.

Rufe’s face was grim. His lips were parted over clenched teeth. He

did not answer my question. It had begun to rain again. For a moment I was

blinded, then I froze to immobility as a big pine log headed directly toward us.

Rufe rowed like mad. Then, he thrust an oar against the log—not to divert it

from its course—but to try to push our boat away from sure destruction. The log

swept by, missing us by a straw.

“That one was close,” Rufe gasped. His face was the color of the

foam that swirled around the boulders. Then he grinned.

I bowed my head, and the water ran in a stream

from my felt hat. The river seemed to thunder louder, and the wind slammed like

a loose shutter at our backs. Our craft was caught in a whirlpool and spun

almost in a circle. Rufe grabbed the branches of a spruce tree that had been

blown down with its top in the river. He pulled with all his might, and the boat

slid out of the current between the tree and the bank.

Rufe yelled at me to jump, while he steadied the boat. I scrambled

up the slippery bank. Rufe followed, and pulled the boat up on the bore where he

left it. We had landed 100 yards downstream from where we started, in spite of

Rufe’s having rowed upstream all the way.

He

looked at me and grinned once more.

“How was that, Doc, for a quick crossing?” he

said.

“I’m glad that’s over,” I said.

I stood for an instant watching the deluge sweep down the valley.

The rain had stopped as suddenly as it had begun. We climbed a steep hill for

more than a mile to Rufe’s farm. By crossing the river and climbing the hill, we

had saved ourselves from walking four miles on the railroad track.

A Cheat Mountain Club logbook entry

describes Thomas McGowan’s experience of another flood in that same year:

November 25, 1907

9:30 p.m.—Heavy

rains. Stage of water four feet above bank of bottom ground. Boardwalks, stove

wood gone. Dog in kennel liberated. Provisions, such as flour, sugar and meal,

removed to upper stories. Old boat ready for emergency. Hired man scared and

will now depart for the hills. We will hold the fort as long as we can and

imagine that we will have to change socks within a short time if rain continues.

Water now up to third step. Folks a little scared. There will be no sleep or

rest tonight. The tempest and roaring of water and extra darkness of night is

awful, but we believe the clubhouse on the Cheat and property of the Cheat

Mountain Sportsmen’s association is the second ark that will hold her inmates

safe.

12–2 a.m.—Water

still rising fast. Flood of July 1897 reached. No one wishes to retire. Chickens

and cats begin squalling. Drift logs and trees are bumping foundations, and

affairs generally are getting doubtful. I expect water on floor in main clubroom

soon and made preparations to save furniture. We expect no mail for several days

now. Road to bridge inundated and out of sight. River continues to give us the

paramount issue of a watery campaign. All our wood for stove and fireplace is

gone and will be in a bit of a fix for some days on account.

2 a.m.—Water

still rising.

7 a.m.—Twenty-six

boardwalk steps to our warehouses gone. Twelve feet of bank behind club house

partly sunk and gone. Much or nearly all wood gone out. Trees undermined on bank

of stream and ready to fall into river. The park around clubhouse’s cyclone

struck: full of big rotten and green trees, rubbish, sand, roots, bark, and even

rocks. Considerable damage done to crib work above clubhouse and old dam part

below clubhouse. All but two bridges between New Hatchery and Cheat Bridge

washed away.

Black

Cloud and Rolling River

This was the flood that led to the creation of the Monongahela

National Forest, whose stated purpose was to protect the headwaters of the

Monongahela River. But timbering activity barely slowed down.

Hazel Phillips (b. 1919) recalls:

Now, when I was small, of course, they

timbered. The Porterwood Timber Company timbered up there on the opposite side

of the river. They started in 1913, and then they disbanded the train. They

finished the logging in 1927. It doesn’t do it now, but I guess they clear-cut

the timber so close that there was nothing to hold the water back.

Mother would say, “No going to the river

today. There was a black cloud up the river last night, and it may come down in

a roll.”

It don’t do it now, but it would come down

that river in a roll that big (she raises her arm chest high). And see, there

was nothing to hold that water back because they timbered it all. Those hollers,

they just, you know, every half mile or so there was a holler. And it would all

feed in, and it would just . . . Mother would say that, and sure enough, you’d

look out and someone would say, “There goes the river.”

There were numerous floods throughout the years, some devastating,

others not so damaging. Increased settlements in the river floodplains led to

more risk of flooding.

Leo Weese recalls a time when the

Shavers Fork flooded Spruce:

I remember one time, that river used to be

full of beaver dams up where Snowshoe is now—it goes into a big bowl, and it

flattens out—and down from that bowl it was nothing but rapids for about a mile

and a half. Well, up in that bowl was a beaver dam, and up came a flash f lood

one time . . . it had to have been ‘46–‘47, somewhere in there. You could see it

raining and raining, and it wasn’t even raining up in Spruce.

lood

one time . . . it had to have been ‘46–‘47, somewhere in there. You could see it

raining and raining, and it wasn’t even raining up in Spruce.

You know where the bridge is above the town of

Spruce? It almost went over the top of that there, and then it opened up after

that. It widened and took out two of the river bridges down below there, where

the shops was—the shops where they worked on the engines—it took them two out.

That was back in the ‘40s. That was right as Spruce was closing down.

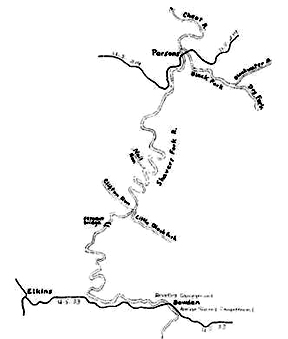

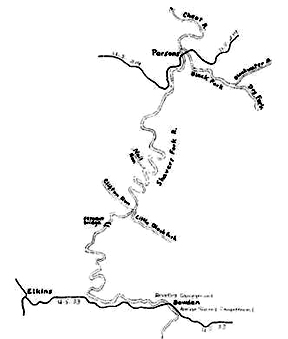

Watershed Floods

Most watersheds are shaped like a big tree, gathering water from

many small creeks and coming together at the “trunk,” gradually making it bigger

and bigger. The Shavers Fork watershed is shaped more like a finger, with very

short streams feeding the mainstem. The high volume of rain falling on the

watershed, combined with the steepness of the river all contribute to the high

frequency of flooding.

Jim Phillips remembers growing up in

Parsons during the 1930’s and 40’s:

Practically every spring we had to be

evacuated. Here come the spring thaw and spring rains, and we was up in the

school building. An old neighbor of mine had an old Model T Ford, and he would

come down there to pick up his two daughters. I will never forget—I always

wanted to ride that old Model T Ford—he pulled up in front of that old school

and told the girls to get in.

And he said, “Jimmy, would you like to go up

the hill with us?”

I said, “I sure would.”

He opened that little door, and I got in. I

poked my head out and watched those little skinny wooden spoke wheels as they

separated the water—about two feet of water then when we evacuated.

These floods were nothing, however, compared to the 1985 flood,

which has been

called

a thousand-year flood because of the rarity of the weather events that

surrounded the flood. September 1985 was the driest month on record, followed in

November by the wettest month. More than a foot of water fell in the area in

that month—6.3 inches of rain fell between 8 a.m. and midnight on November 4,

1985 (Parsons Advocate, December 11, 1985).

This heavy rain, flowing over the already

saturated land, swept through the watershed like none before it. Parsons,

sitting in the floodplain where the Black Fork and Shavers Fork rivers meet to

create the Cheat River, was the worst hit city in the state.

Hayward Phillips, then in his late

50’s, lived just outside of Parsons in 1985:

The Black Fork and the Shavers Fork form [the

Cheat River] below Parsons, and during that ‘85 flood they formed in

Parsons. That’s the reason Parsons was damaged so bad.

Yeah, we were living here during that flood. Our pond flooded the

basement. But that’s it. I remember the night before I drove home, and there

were some stumps on the road but nothing too serious. The water was high but not

over the road. It was just lapping.

I drove on and I thought, “What are those

people on the bridge for?” But I came home and the next morning, I told my wife,

I said, “Maryanne, what is that roaring?”

I heard this roaring and timber crashing and

banging. So I went and climbed up on the hill and saw the river flowing over

everything. It took houses and all but we didn’t even know about it at the time.

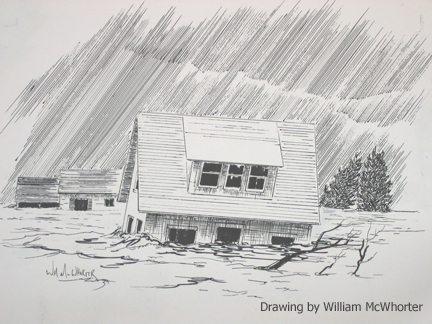

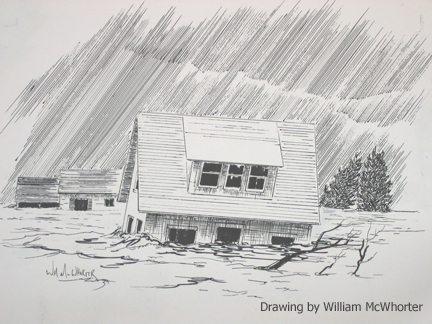

Farmhouse: This is the Shaffer’s old house right

after

the ’85 flood (taken Nov 5). The flood came and moved their

house into

that hill. It was later burned.

Photo courtesy Hazel Shaffer Phillips

January

21st 1996, a photo from Parsons.

In the background is the insurance building that was

lifted off its foundation and thrown around town.

Photo courtesy Grace Shaffer Gainer.

Bowden also got hit pretty hard.

Jim Bazzle,

owner of Revelle’s River Resorts, recalls witnessing the river’s power:

In 1985, it

was November the 4th if I am not mistaken. That was the date of that

hundred-year flood. Of course, it caused massive damage here. We were sitting

here in front of our camper center and water was up to about this windowsill on

this building. So, you can imagine that river running, you know, at that level,

just all through here.

Sections

would be moving very quickly, and other parts would either be kind of back, so

there would be sections where the water would be still but running down where

his truck is right now. It tore up the road. It tore up the little bridges. I

mean, it was extremely destructive. Unfortunately, the old Western Maryland

railway station had been relocated across from Mr. Vance’s house and the water

picked that old station up—he was using it as a wood house, I believe—and took

it down, the water did, into our store, which we were hoping to preserve. It

knocked the foundation out from under the building.

We also had a

small church sitting on a site just beyond where that trailer is located right

now. My aunt and uncle had helped build that back in the early 1900s as a

Methodist church and it was picked up and it went down and crashed into one of

our bathhouses. It pretty much demolished the bathhouse. It wasn’t so much water

damage that we had on our property—well, on the grounds there was tremendous

water damage—but in terms of buildings, the destruction was mostly debris or

other buildings hitting into buildings.

I mean, here

was this church floating in the river and the railway station, campers, these

units. These camping units, just like these units that you see sitting here

today, we had a large number of them down in this area, right down here where

these trucks are. All of them were picked up and moved downriver. Some floated

all the way down the Cheat River Bridge, three or four miles down river. Others

came crashing into trees and sort of stayed on our grounds. We have pictures of

these units. It was just like the water picked them up and, you know, they

weighed 10,000 pounds! That’s hard to believe that water would have that much

power and velocity to be able to pick up 5-, 10-, 15,000-pound-units and just

take them downstream.

In 1985,

there was the old bridge—the old super-structure blue bridge that was across

here at Bowden—and it had been there my entire lifetime. I remember my father

had gotten everyone out of here that he could. I

mean, no one was ever lost here

but in 1985 he was up there at 7 in the morning and was actually standing out on

the edge of the bridge feeling it shaking. Within about thirty minutes, that

bridge, literally, was taken down river. He stood—several people there witnessed

it—and that was quite something.

mean, no one was ever lost here

but in 1985 he was up there at 7 in the morning and was actually standing out on

the edge of the bridge feeling it shaking. Within about thirty minutes, that

bridge, literally, was taken down river. He stood—several people there witnessed

it—and that was quite something.

A

camper trailer completely trashed from the flood.

Many of these trailers were

simply picked up and washed

downstream until they broke apart or hit something

very solid.

Photo courtesy Chuck Hayhurst

It wasn’t just the Shavers Fork that got hit

that day.

Leo Weese tells of his adventurous ride home

from work that day:

You know that

flood they had in 1985? I was working in a mine down by Buckhannon.

We come out

of there, and I had to go all the way around Buckhannon. I got all the way

around there, and I finally got to [Route] 33 and I come out through and down

over and come out to Crystal Springs, the lower part of it.

We come out

of there, and I had to go all the way around Buckhannon. I got all the way

around there, and I finally got to [Route] 33 and I come out through and down

over and come out to Crystal Springs, the lower part of it.

I saw it, and I thought, hmm. Well, I’ll never

get around it that way. So I headed through Harpertown, which goes around the

backside. I got through Harpertown to Cravensdale where there is a bridge. There

was water on both sides of that bridge. There was a Harman boy by the bridge,

and I asked, “Is that bridge still in there?”

He said, “Yeah, it’s still there.”

So I put it in four-wheel drive, aimed at that

bridge, and shot across that bridge. And when I got to the other side, I felt

something [slap!] thump down. I had it in four-wheel drive and I had it wide

open so I just kept on driving.

Well, I didn’t know it at the time, but I ran

into that Harman boy later, and he said, “That bridge went out right back of

you.” I said, ”I thought it did because I felt the dog-gone bridge gone out.”

Anyway, I go up across the mountain to

Fairview schoolhouse, up across the mountain, down Lower Cheat—for about a mile

right there, you’re right on top of that river—until you get to this road right

here: it comes across. You never heard nothing like that in your life! A

roaring. The river run like that. I was afraid that bank might just disappear.

You never heard nothing like it. And the next day, it washed Parsons and St.

George out all the way. I barely made it home that day. If I had gone any other

way, I wouldn’t have made it.

Destruction and

Cleanup

Boone Hall recalls his experience at

Bowden:

Stuarts Park after

the ‘85 flood? I could tell you lots about that. My friend called me, and we

started moving furniture out of her trailer. And we saw that water just go down.

I saw a church—a church that floated all the way down to Cheat River Bridge. It

was in one piece, and it hit that bridge and just exploded.

There was an iron bridge up here, and it made

it clear down to here. Iron! And the fish—it got the hatchery—there was fish all

over. I’d seen a lot of bad things happen. For about two weeks, I helped clean

the place up.

The

flood of ’85 at the Alpine Shores campground. While the photo might lead you to

believe that water is simply covering a lot of the ground, much of that water is

moving with tremendous force. It will also deposit a lot of debris on that

plain when the water subsides. Photo courtesy Chuck Hayhurst

Cleanup from this natural disaster was immense. There was so much destruction in

the area that many people paused their lives to help their neighbors get back on

track.

“Week of

November Tenth 1985: Worked 117.5 hours.”— Kenny Watson, Track Crew for

Western Maryland

Kenny Watson recalls that week in November

as the busiest week of his career:

The ‘85 flood killed

the railroad more or less. We were out about two weeks straight and stayed out.

You know, you’d go home—a lot of times, I’d go home—get my lunch bucket repacked

and then go back. We were staying in the caboose at the Bayard yards, and it was

winter. It was cold. A lot of guys had lost their homes, and they were right out

there because that was the important thing, to get the train through.

The biggest

thing that I worked on at the Shavers Fork was right down below the Greenbrier

Junction. There’s a real steep place there right below where the railroad bridge

is. It was right after the ‘85 flood. I was working over in Bayard and they

called us over there—it had all slipped, and it was so wet—and we went in there

at night and the bridge and building crew had been cribbing that whole side of

the hill, right after the flood.

What happened

is we worked all night getting that cribbed up, and then they would bring

carloads of ballast in. They were just knocking the pockets. I mean, just whole

carloads going down in there like there was nothing. We finally got it filled

up—and about the time we got it filled up, the cribbing broke—and just

everything that we had done went right back down the river.

I mean it was hours and hours and hours of

filling and cribbing this up and cribbing that up. And it was all going right in

the river. The river was still high—Shavers Fork—and it was gone. Hundreds of

crossties and I don’t know how many loads of stone—and just that fast, you know?

We were looking at it just piled up like four–five feet above the tracks, and

next thing you know, it was all gone.

Cookie Ladies Go

to Washington, D.C.

Parsons relief work was ongoing. One silver lining of the disaster

was the formation of the famous “Cookie Ladies,” who raised money to prevent

further flooding in Parsons though grassroots events, such as bake sales and

garage sales. They have worked on creating a floodwall for Parsons as well as a

veterans’ memorial.

Grace Gainer is one of the wonderful Cookie

Ladies:

We are the Cookie

Ladies, and this is where they paid our way and we got to go to Washington. They

put us in a motel for three days. They had a big banquet, and they brought the

Cookie Ladies up. We got a standing ovation—600 people out there. We were the

only ones to get a standing ovation when all the talking was done. We really had

a nice time.

We had a bunch of cookbooks, and we had sold

some of them. Someone said that we could sell the rest of them down in the

lobby, and we got down in the middle and started yelling, “Cookie Ladies’

cookbooks!”

We were selling them for $15 and some folks

gave us $20. We sold all our books. We’ve done lots of work on the river. We’ve

probably put $40,000–50,000 dollars into the river, with a lot of help and a lot

of volunteers.

-

Cookie

ladies: Joan Davis, Grace Gainer, Julie Little, and Hazel Phillips in

Washington D.C. FEMA flew them out there for the work that they had done.

They

were at the time known as the CCC (Concerned Citizen’s Coalition). Photo taken

December of 1998, courtesy of Hazel Phillips

Twin 1996 Floods

That wasn’t the end of the flooding—1996 saw another flood, which

actually rose higher in some places than the ‘85 flood had. In total damage, it

wasn’t even comparable. What was remarkable about 1996 is that there were twin

floods.

Jim Bazzle explains:

That [January 1996] flood resulted in two or

three months of clean up. The thing that was really significant was my father

was managing this—and he was getting up in years, in his 70s—so this was very,

very hard on him. We had literally just recovered from this flood and put

everything back in place, and it was starting to look green again and nice. And

that same year, 1996, we had a second flood, almost identical in height etc. to

the earlier one in January. Flooding almost to the same inch. It was eerie.

Now, the one in January could be explained

because of the time of year, it’s always a risk from November 1 to May 1, but

this was the week before Memorial Day. Normally we just don’t have high water

here over the summer months. What was ironic about it was we had flood

insurance—we did have damage to some of our buildings and the insurance had just

settled with my Dad—and then it happened again. And the settlement on the second

go-round, the second flood, was almost identical to the first. It was eerie.

We lost

almost 50 percent of our revenue that year. The only salvation was the flood

insurance. Since ‘96 we haven’t had significant flooding. However, every year

we’ve had one or two close calls but the water receded. It seems that in recent

years, as a result of mining or timber being taken above us, that the potential

for flooding is greater than it ever has been.

It just seems to me that there’s more risk

these days. I’m more concerned. I think timbering practices are much better

these days, permitted and controlled. However, people continue to cut lots of

trees, even for farming, hunting camp. Part of our protection is having that

forest base. It remains a concern. But we live with it.

Chuck

Hayhurst and his wife were evacuated from a section of Jim Bazzle’s campground

that had become an island during the flooding:

Now, we got

evacuated here in the flood of ‘96. It was 2 o’clock in the morning and Elkins

Fire Department come up, gave us ten

minutes to get out. There was probably

twenty-five or thirty motor homes down in the bottom here, and we were the only

ones up here on this end.

minutes to get out. There was probably

twenty-five or thirty motor homes down in the bottom here, and we were the only

ones up here on this end.

They took us up to a maintenance building, and

their fire engine was over by the railroad tracks. They had cables thrown across

there to the maintenance building. There was probably ten foot of backwater. My

wife wasn’t on oxygen then, but she is on oxygen now, and she had a breathing

problem. They give us ten minutes to get ready and get out of here. We left the

lights on. We left the door open, everything.

We thought, well, this is it. We left the car

set, and we got in the boat, in a little old canoe-type boat. There was about

six inches of water in the bottom of the boat, and you couldn’t sit on the seat.

The seats were up higher and they wanted you down in the boat. We were the first

ones across on account of her breathing problems. And here come a camper

floating down the river.

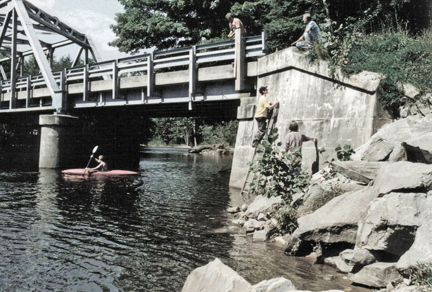

The

Cheat River Bridge in Bowden during the first ’96 flood. Taken from the deck of

the Shavers Fork Store. Photo courtesy Henry Nefflen

Rising Rivers,

Weather Reports

Fortunately, the boat made it back to shore and after waiting until

the camper had past, they made a second, successful attempt. Nonetheless,

flooding is a fact of life on the Shavers Fork. There’s been some work on the

river, but floodwalls simply rush the water downstream to the next town.

Dredging the river would be an incredibly

expensive and perhaps futile effort.

In the end, gauges were installed to monitor water levels. Gauges at Cheat

Bridge and Bemis now serve as rulers to help determine how bad the flooding will

be and if it is continuing to rise.

Jim Bazzle explains:

One significant

change is that the weather reporting [Early Warning System] coming to us is much

better now. The Shavers Fork, which I understand is one of the fastest rivers on

the east coast, forms on Cheat Mountain. By the time it gets here, it’s normally

moving pretty good so I am concerned about what’s happening on the watershed above us. At times the river will actually come down as a tidal wave, a wall,

anywhere from a few inches to a few feet in height.

We contact a

person in Bemis who watches a gauge. That is extremely helpful. I think that

person, those people, they also report to the state police or to some central

agency. There is a system in place.

I just sort of plug into it to check with

this one person in particular because it’s about seven miles upstream and that

tells me what I need to know.

I just sort of plug into it to check with

this one person in particular because it’s about seven miles upstream and that

tells me what I need to know.

Recently, for example, we had high water, and

we were concerned. We call him at eleven in

the morning, and he says the water is now receding; it’s down five inches. Water

was still a little bit higher here but if he tells me that, then I’m relieved.

If he said the water is a foot higher here than it was at seven this morning,

then I’m more concerned. But, that is not exact science.

-

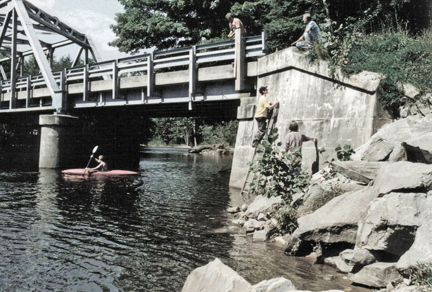

River

gage: These river gages are placed at various bridges so that flooding can be

better predicted. By showing what the level of the water is upstream, people

lower down on the river are able to know if the river will continue to rise and

by how much. Here members of the Shavers Fork Coalition work to repaint one of

the river gages in 1997. Photo courtesy Shavers Fork Coalition

Flash Floods,

Fast Water

Jim Bazzle briefly mentions the flash floods that rush down the

river. Many believe this is how the Cheat River got its name because if a person

were caught in the middle of the river during one of these waves, there wouldn’t

be enough time to escape.

Bill Thorne wrote about experiencing a flash

flood with his son David:

David and I were

fishing just above Glade Run. It got very dark and looked like it might rain

but didn’t. A short time later, we were on different sides of the river when it

started to rise. David backed up to the railroad, and I got to the west side of

the river. The truck was on the west side at Crouch Run over a mile away.

We started

that way, and the water kept rising. David arrived at Crouch Run long before me

and couldn’t cross. I was worried because I was not there.

The riverbank

is very dense with rhododendron and mountain laurel and you couldn’t walk the

bank. I had to walk in the water holding on to the brush. I put my wallet in my

shirt pocket, but it got all wet, along with my flies and other equipment. I

held my fly rod with my right hand as I held the brush with my left. Many times

the muddy water was up to my arms, and it took a long time to walk the mile or

more this way. The edge where I was walking would have been high and dry when

the water is normal. The river probably raised eight or ten feet.

When I got

close to Crouch Run, people were yelling for me because David had been there

quite some time by the railroad. When I arrived, we had to figure out how to get

him over. It was decided he’d walk back to Glade Run and go up the trail to the

Forest Service road, and I would drive around and pick him up a distance of

twenty miles or so. As it turned out, he couldn’t find the trail and had to

bushwhack his way up Glade Run.

I changed my

clothes and fixed a cup of spirits to calm down, then drove around to pick up

David. It was very scary at times but staying calm and not trying to cross the

raging current was important.

And maybe twice in my life, and I looked up and

there came a big wall of water with cross ties and we yelled at the kids to get

out of the water. It can be that sudden, you can look up and see a

four-foot wall of water coming down. It’s the rain on high Cheat that gets

it.

-Lorraine Burke

Leo Weese shares a similar experience:

I was fishing one

time up here in Bowden. I was fly-fishing and it was raining. It was just

drizzling down here but it was dark upstream. I was in the riffles, and I

started catching. I noticed that before the water was at my calves and now the

water was at my knees. Then it got up to the middle of my thighs, and I looked

upstream, and you could see it coming. By the time I got to the bank . . . I

just about didn’t make it. That’s how fast that river comes up. It’ll come up

fast. It doesn’t have to be raining. It could be fine where you are, and it’d be

dark up at the top of the mountain. What happens is those beaver dams get full,

and they start busting loose, and they break and send it all down.P

Kenny Watson tells about rising water:

I got in trouble

fishing over there on Shavers Fork one time. The water caught me. We were bass

fishing—and I knew enough about the river—I knew Shavers Fork because I’ve spent

so much time there. It was a beautiful day but stuff started coming down, you

know, getting a little milky. I mean, it was low, but by the time I got across .

. . if I had waited at any time, I wouldn’t have been able to get across the

river.

I was trout

fishing one time in the spring, and I heard this noise—it was a wall of ice, and

it had broke loose from up above somewhere. It was scary. I got out of there OK

and everything. That was probably about twenty years ago.

RIVER FABLE

By Kenny Watson

Who could foretell the

river's rise

as you sit tying red and

yellow

flies in a gold-filtered

afternoon.

In a magic tree house

suspended by

hemlock, maple and

locust

entwined in dutchman's

pipe,

you, contemplate trout.

Across a river running

low, you set course.

Without warning, water

inches toward

your wader tops while

you recite

the litany of

rivers—Black, Dry,

Gandy, Laurel, and

Shavers.

All forks of the Cheat.

Trapped between this

rock cliff

and stony river bottom

on a

cloudless October day.

As waters

deepen you watch shadows

lengthen

into evening. With the

moon's rise

a silver bridge spans

the swollen flow

and you cross with ease

to the other side.

When Henry Nefflen was a kid, he seems to

have gotten the worst of one instant flood:

Another time Leo

Weese and I went down the river from Cheat Bridge to a place called McGee Run.

We found us a nice place on the river and made a camp there. A day or two before

our parents were to pick us up, I woke up—I had taken a cot with me, I think we

both had cots because our parents could drive us to where we were going to

stay—and I woke up and there was water almost to the top of my cot.

There was stuff floating around. The river had

come up overnight, and everything was soaking wet. There was ten to twelve miles

from McGee Run to the highway. There was no way we could stay. The only thing

that was dry was our sleeping bags, and they were getting wet from the humidity.

We had a hell of a time trying to catch our

stuff and take down our tent as it floated downriver. So we started out of

there. I was wearing a red leather hat. Some guy came out of the Linan mine. He

stopped to pick us up because he thought I had cracked my head open. Dye was

running over me. He took us to the highway, and we then wanted to go and call

from the Pocahontas Motel, which is right on the county line. We got another

ride and got there, and they still had a crank phone that we used.

TWENTY-SIX STEPS

By

Ann E. Krueger

Many days he would stand

on the porch above the river

bank, and comment on the

length of time the roots

of the locust had held it

cantilevered over the water.

He watched it year after year

through the change of seasons,

during the rise and retreat of floods

while the melt of snow and ice

eroded the earth around it and

wind whipped its leaves and branches.

He talked about that tree; the fence

posts it would make, the number

of board feet it held, when it

would fall, the amount of heat it would

give off. Locust burns hot, you know,

he would say. He went into town one

morning, and when he returned, it had

fallen, its branches in the river with

the current pulling it down stream.

He got his saw, waded into the river

to cut the tree into pieces. All that day

and the next each time he went up the

twenty-six steps from the river to his

cabin with a chunk of locust under

each arm, and each time he went

back down the twenty-six steps to get

more, he thought of the tree and how

he had wanted to be there when it fell.

Link to

Chapter Ten

West Virginia is a water wealthy state. And after Pickens in

southwestern Randolph County, Shavers Fork and Cheat Mountain are the wettest

areas in the state. Combined with the high altitude, this creates some nasty

weather atop the mountain. This high ridge had always been an obstacle in

European immigrants’ move westward. It wasn’t until the 1830s that a wagon

road—the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike—was built to cross Cheat Mountain. Modern

day U.S. Route 250 follows much of the old turnpike’s path over Cheat Mountain,

crossing the river at Cheat Bridge and descending

on the other side.

West Virginia is a water wealthy state. And after Pickens in

southwestern Randolph County, Shavers Fork and Cheat Mountain are the wettest

areas in the state. Combined with the high altitude, this creates some nasty

weather atop the mountain. This high ridge had always been an obstacle in

European immigrants’ move westward. It wasn’t until the 1830s that a wagon

road—the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike—was built to cross Cheat Mountain. Modern

day U.S. Route 250 follows much of the old turnpike’s path over Cheat Mountain,

crossing the river at Cheat Bridge and descending

on the other side. lood

one time . . . it had to have been ‘46–‘47, somewhere in there. You could see it

raining and raining, and it wasn’t even raining up in Spruce.

lood

one time . . . it had to have been ‘46–‘47, somewhere in there. You could see it

raining and raining, and it wasn’t even raining up in Spruce.

mean, no one was ever lost here

but in 1985 he was up there at 7 in the morning and was actually standing out on

the edge of the bridge feeling it shaking. Within about thirty minutes, that

bridge, literally, was taken down river. He stood—several people there witnessed

it—and that was quite something.

mean, no one was ever lost here

but in 1985 he was up there at 7 in the morning and was actually standing out on

the edge of the bridge feeling it shaking. Within about thirty minutes, that

bridge, literally, was taken down river. He stood—several people there witnessed

it—and that was quite something. We come out

of there, and I had to go all the way around Buckhannon. I got all the way

around there, and I finally got to [Route] 33 and I come out through and down

over and come out to Crystal Springs, the lower part of it.

We come out

of there, and I had to go all the way around Buckhannon. I got all the way

around there, and I finally got to [Route] 33 and I come out through and down

over and come out to Crystal Springs, the lower part of it.

minutes to get out. There was probably

twenty-five or thirty motor homes down in the bottom here, and we were the only

ones up here on this end.

minutes to get out. There was probably

twenty-five or thirty motor homes down in the bottom here, and we were the only

ones up here on this end.  I just sort of plug into it to check with

this one person in particular because it’s about seven miles upstream and that

tells me what I need to know.

I just sort of plug into it to check with

this one person in particular because it’s about seven miles upstream and that

tells me what I need to know.