“The red brick building in Parsons was once a woolen mill where they made blankets. At 3 or 3:30, you knew it was shift change because the river would turn red, green, blue. They would dump the dye into the river. When you saw it you knew about what time it was. The river would be several different colors for a while. Today you couldn’t do that. Be out of business.”—Steve Lambert

The Shavers Fork story ends where the river joins the Black Fork to form the mighty Cheat River. The city of Parsons is nestled in this spot. It is one of the first places pioneers settled when they migrated to the area in the late eighteenth century. Having a wealth of good bottomland to farm, the town prospered. Floods created this bottomland, and it didn’t take long for the residents to discover that Parsons floods almost every year.

Parsons’ early history is well documented: three histories of Tucker County have been written. In addition, Harry Adolphus Ridgway wrote about his memories of the town of Parsons in a series of articles from October 21, 1943–March 2, 1944.

Ridgway explains much about Parsons’ early history (Parsons Advocate, 1943–1944):

To begin with dates, I will say that I came to this county in September 1877 as a clerk for my Uncle James W. Bowman at Hendricks, West Virginia. The West Virginia Central Railroad was then building down from Thomas, but not as yet further down than Tub Run. My uncle got the first goods, which came over the West Virginia Central Railroad Company line, which he had to have hauled from Tub Run on a wagon.

The railroad grade was made through Hendricks by a large number of Virginia Negroes. They went to work singing and quit their work the same way. The grade was along the river. It was washed out by the 1888 flood and had to be re-graded and placed where it now is located. The crossing of the Black Fork river by the railroad bridge was to be down the river some feet and the grade lowered but owing to the flood of 1888 the grade was made as now, and the bridge was not erected until the winter and spring of 1889.

The bridge in Parsons across the Shavers Fork River was completed, and the first engine to run over this bridge was run by Uncle Tom Daugherty and the pilot was ridden by “Billy” Bickey. This was May 29, 1889, and Parsons was then called Job.

The name of Job for Parsons was of very short duration, for Mr. Ward Parsons met with Job Parsons (who had a store and post office near his home up on the Dry Fork, which was named Parsons) and their meeting soon roned (sic) out for each place if the Post Office Department would accept same and they did, so Parsons was named Job and the name Parsons was carried to the present little city.

- The Parsons’ Valley before most of the development came through. The area was prime farmland for the first settlers, as thousands of years of floods had creating a rich topsoil. Photo courtesy Tucker County Historical Society.

Rumor has it that the town’s name was actually determined by a draw of cards. The town was then named Job after a prominent early settler. His son, also named Job, moved to Randolph County where he established another community, then called Parsons.

One day Ward Parsons approached Job Parsons and proposed a name switch, but Job Parsons didn’t want to change the name of his town. They decided to draw cards to decide if the switch was to take place. Ward Parsons, having drawn the three of hearts, walked away, but was called back when Job Parsons drew the two of spades (Long, 9).

Harry Ridgway continues:

The first house built in Parsons, West Virginia, was what is now called the Hebb property, in which building Bubar and Bible had their store. It was a combination of business-house and dwelling, but the first dwelling house is where Miss Sill now lives. It was built for Thadeus McKinney.

A little later, the next dwelling was just across the street from Miss Sill’s property, it being built for French Long. I am now speaking for the town of Parsons. There were four dwellings in what is now Parsons before the town was laid out as a town. The four were Currance, Snyder, Parsons and Corricks. The east side of Shavers Fork was owned by Currance and Snyder; the west side was owned by Parsons and Corrick.

Among the first houses

built in town was one built by the West Virginia Central Railroad,

near where the Dorman Mills now stands. I remember when Howard Shaffer was

living there, and the waters became so high that Mrs. Shaffer had to be carried

out on a stretcher, and the men had to wade almost waist deep to get her out of

the water.

so high that Mrs. Shaffer had to be carried

out on a stretcher, and the men had to wade almost waist deep to get her out of

the water.

The first church built in Parsons was on the hill above what is now the Moose Hall. It was built in 1898, and W.N. Doolittle was the foreman of said building. Since that time the old church has been turned round, and an addition has been built to same. In the last year repairs have been made on the church, greatly improving the appearance of the interior of the building. The second church was built two years later. It was the old M. P. Church but has been torn down and a brick church has been built; not on the same lot, but on River Street, east of Shavers Fork of Cheat River. Downtown Parsons circa 1902. Photo courtesy Tucker County Historical Society.

The pulp mill was built

in Parsons in the year 1900. Hugh Pritt said he was the first man to drive a

stake for the building, and if he lived he would be the last man to pull up the

last stake; and he was, for the mill closed down on the 17th day of

July, 1927. Later all the property belonging to the mill company was sold at

public auction and Hugh Pritt had

associated

himself with others that bought all the property of the mill.

associated

himself with others that bought all the property of the mill.

His last bid, which bought the mill, was $36,100.00. I’m told that the day of the sale he said he was going to buy the mill and had taken out many bonds and carried them in his pockets until the sale was over. He had close competition by several Jewish people who wanted the mill for its parts. But Mr. Pritt outbid them and got the mill, and later he sold a good portion of the equipment to James Wilt who moved it out west where he (Mr. Wilt) was superintendent of a like mill in the west.

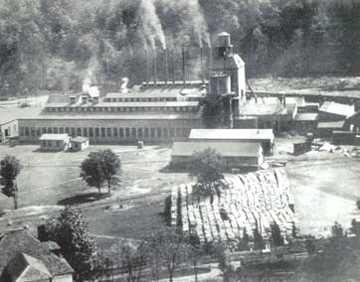

- A photograph of the old Parsons Lumber Company Pulp Mill from 1905. Among the men is Lloyd Shaffer, Hazel Phillips and Grace Gainer’s Father. This photograph, like many other historical documents was damaged in the flood of ’85. Photo courtesy Hazel Phillips

The flood of 1888 was the greatest flood ever to come upon the Cheat River—so old people told me. The whole valley from Parsons to far below Rowlesburg was under water except a small portion of the Sam Wamsley farm, about three acres. There were horses, cattle, sheep and hogs, which went down the river never to be seen or heard from. Some hogs were reported as missing and were found with their throats cut from swimming, for it is said that a hog will cut its throat if it has to swim far and especially if the hog is fat. Such were the reports of some of the hogs which were caught in the swollen river.

Parsons Incorporates

Parsons became incorporated as a town on June 12, 1893, and incorporated as a city on February 18, 1907. On August 7, 1907, it became the county seat but some of the residents couldn't wait that long.

Harry Ridgway again reminisces:

The first petition presented to the County Court for the relocation of the Court House from St. George to Parsons, West Virginia, was presented to the Court April 9, 1890. The County Court was again petitioned on the relocation of the Court House on July 11, 1890.

The third petition was presented to County Court on Oct. 8, 1890, and after this petition, the county court ordered a special election to be held on the 28th day of April, 1893. The ballot commissioners were directed to have printed on the ballot “For Relocation” and also “Against Relocation.”

The result of said election was 689 for relocation and 576 against. The County Court was advised that the rent on the building to be used as the courthouse was to be free for four years. Those guaranteeing the rent were C.J. McKinney, W.N. Doolittle, J. M. Talbott, Ward Parsons, S.E. Parsons, J.W. Pifer, C.E. Glenn, and L.W. Parsons.

Hendricks asked that the

county court grant Hendricks the right to vote upon the relocation of the

residents offered to guarantee the cost of the

election but the county court

turned the application down.

One comical gesture was in moving the court records from St. George: when all was about ready to go to St. George to remove the records, Dr. B.B. Baker was selected to go down the river and cut telephone lines so there could be no communications to St. George. It is reported that he went down to St. George, climbed a telephone pole and cut the line in St. George.

He was asked why he was so doing and his answer was, “The Parsons people are coming to move the records and do not want the St. George people to know about it.”

But the records were removed as per schedule of the Parsons people and into the building, which is now a lodge hall beside the Advocate building. This was the new home for the County Court and remained there until the new courthouse was completed.

The removal of the records from St. George, West Virginia, was made on the 4th day of August 1893, and remained there until the new courthouse was built when the records were then removed to the present courthouse. The circuit clerk was Mr. C.W. Minear and the county clerk was Mr. Cayton.

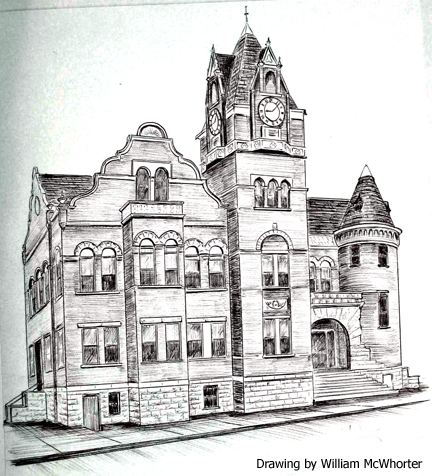

Tucker County Court House in Parsons.

Parsons grew quickly during this time. In 1893, it experienced another boom when Thomas Gould and his sister Abbie Gould built a tannery next to the Shavers Fork (Fansler, 383). This tannery was one of Parsons’ mainstays.

Jim Phillips, a Parsons native, recalls some memories involving the tannery:

I worked at the tannery. I’m talking about little periods of time, like eight months here and there, between jobs. I worked the tannery on two different occasions, and both of them, we was building a ‘pollution dilution’ plant. The environmental people was coming down on them because they was dumping chemicals right straight into the river.

The fleshings right off of the cowhides, you know? Tanning was done by an alkalinity (sic) solution of lime and calcium to soften them up in what they called the limes. Put the hide down there, and then you scrape them off. It was bad, and it was killing everything downriver.

In 1948, I think it was before I went in the Army, and when I told the boss that Joe Phillips was my dad, well, I got the job because my dad was known to be a hard worker and an honest person. Thank God. I was just a kid, you know, but very strong, and determined.

So I got the job, and I worked on the filtration plant there until that job was completed. And at that time, in fact, just to reminisce . . . those old guys was hard workers. Some of them worked there forty years or so pulling leather. I’ve seen ‘em. They take great big hooks on poles, and all day long they pull that old cowhide out and slap it on a trailer or car or something like that. And then take them up to the bark shed.

This

guy died the other day—him and his brother pulled leather there as a team—you

need two people. They pulled leather for years and years, and their arms was

just . . . Don’t let them get a hold of you, they’d break you. God, they were

strong. Big strong men but they was harmless! Those people worked hard all week.

They went to the grocery store with their paycheck, and they bought for their

family. They paid their taxes. They drank a little whiskey once in a while but I

never knew them to be drunks.

This

guy died the other day—him and his brother pulled leather there as a team—you

need two people. They pulled leather for years and years, and their arms was

just . . . Don’t let them get a hold of you, they’d break you. God, they were

strong. Big strong men but they was harmless! Those people worked hard all week.

They went to the grocery store with their paycheck, and they bought for their

family. They paid their taxes. They drank a little whiskey once in a while but I

never knew them to be drunks.

We had a strike one time there at the tannery when I was at the sheriff’s office, around ‘62. We didn’t have anybody in the sheriff’s office except me and one deputy. And the superintendent of the tannery called over to my office and said that they needed some help over there at the strike line because they had people that was throwing rocks.

Pictured are the tannery owners out for a ride. These horse drawn carriages were common in West Virginia up until the 1930’s when automobiles finally became established in the area. Photo courtesy Tucker County Historical Society.

So we went over, and when they switched shifts, you see, the strikers wouldn’t let the people go in. They had the scabs. They were going across the picket lines and work for straight wages. Well, the strikers wanted to stop that. So when a scab went across, they’d throw rocks at his car or whatever. They wanted us to go over when they changed shifts. Well, we just couldn’t handle it—me and deputy. We was also having a strike over at Kingsford and a strike over here. Plus everything else at the courthouse and the jailhouse.

I asked the state troopers that was here. They had two, three over here at that time to help us. I said, “You know, we helped you guys. We’d appreciate it if, when the shift changes, you just set your car there. We’re quite sure they won’t tear off a man’s rear view mirror.”

They said, “That’s not our job. We’re highway patrol.”

And I said, “You’re supposed to support the sheriff’s department while you’re here.”

“Nope, we’re not going to do it. That’s your job.”

Well, I just got on the phone and called the state superintendent in Charleston. I said, “Hey, we’ve got a strike over here, and they want us to patrol it. We need help. There’s nobody here but me and my deputy. We just can’t handle it. So I asked the state troopers that’s stationed here to give us a hand, and they refused.”

He said, “Who are they?” I told him who they was. And he said, “How serious is your strike?”

“Serious enough that they requested a patrol be there when they change work schedules,” I said. He asked how many men I needed, and I said, “Well, I think we got enough up here.”

He said, “I’ll send up some. I’ll designate some and send them up to help you because you’re the chief, and you’re in charge. Don’t let those troopers tell you any different. The Sheriff of Tucker County is the chief law enforcer.”

“Well,” I said, “I don’t think we need any more if these guys would just cooperate, you know?”

He said, “They’ll be on the job tomorrow or else I’ll have their badges.”

Boy that one old sergeant was mad. (laughs) He said, “You’re about to go out of office. You’re gonna be giving up that badge. When you do, your ass is mine,” he says. “‘Cause I’m gonna get you for this.”

Parsons

Pulp & Paper and other mills

Parsons Pulp & Paper Company had a short history in Parsons. They built a pulp mill in town that operated from 1902 to 1927 when it was permanently shut down. There was also a planing mill, which was open from 1900 to 1922. Both mills were typical of the boom and bust system of logging at the time. The wool mill was the next major industry to hit town.

- The pulp mill of the Parsons Pulp and Paper Company at Parsons in 1907. It was only operating for 25 years (1902-1927. Luckily, Parsons had other industries in town to keep the town going after the mill closed. Photo courtesy Roy Clarkson.

Harry Ridgway, writing in the mid-1940’s in the Parsons Advocate, recalls the woolen mill:

This mill was built in the year 1922 by the Hall Brothers of Philippi and was called the Philippi Mills. The Hall brothers were also the owners of a similar mill in Philippi. In about three years time, the brothers were forced to sell both mills and the Parsons mill was bought by Thomas Dorman; the one in Philippi was taken over by Franklin Dorman and operated by him for about two years.

Miss Esther A. Sill has been treasurer of this mill for about seventeen years and in all that time has never failed to have the payroll ready and on time. She has plenty of efficient office help. F.W. Dorman, president, is now serving in the Navy as lieutenant, and Theodore T. Dorman is manager.

There have been two

large additions built to the Dorman Mills in the past three years and also an

office of brick and concrete. This mill is operated five days each week and

three shifts each day. It employs about 135 people. This mill was built for the

Philippi Blanket Mill by a contractor from Cleveland, Ohio. T.W. Ryan worked for

this contractor and in his ardent way of doing things, saved the contractor many

dollars.

Grace Gainer, who moved to Parsons after growing up in the 1920’s farther upstream, tells about working at the wool mill:

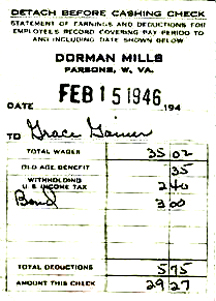

I bet you wouldn’t believe this. It’s when I worked at the mill. I worked there forty years, and I left with no retirement. It shut down in ‘71, but that’s what I was making [see pay stub below]. That was for a week. I worked over there one summer for ten cents an hour for three months, fifty-five hours a week, and I was happy to get it. And no board! And that’s bond. I paid bond that was the last one. I paid two dollars a week, and that’s the only way I could save money. I got one every six weeks. When I got them cashed I had $70.

I come down in ‘28 and started working at the woolen mill. Right over there, where I live, the shoe factory was. They sold the mill, and they put the shoe factory in but the flood washed it out. Then they put it back, and it washed it out again. They washed it out in ‘85 and it washed it out in ‘96. Now they are putting some sort of automobile place in it.

Grace Gainer’s workstub from the wool factory in

1946. Note the war bond taken out of each paycheck. Courtesy Grace

Gainer.

First Man Kingsford Hired

In 1958 more industry moved to Parsons, with Kingsford Charcoal settling in just upriver of the town.

Jim Phillips recalls being the first one the plant hired:

Kingsford Charcoal was starting and my brother and I decided that we would truck some charcoal wood in and help get the plant started. We had some out on the hill. We cut our own wood and trucked it in and we did some trucking there. So they offered me a job up there at Kingsford. In fact, I wore badge number one, I was the first man hired by Kingsford.

One reason for that was my mother—they had a bunkhouse on the plant when they were setting up—and she cooked for them. These guys from Missouri, the engineers and everything stayed there. She was a darn good cook. So she put in a good word for me. Number one badge, right here (taps his chest).

I worked at Kingsford at that time, and I drove an old six-by-six GI truck out there in the yard, lifting kilns for wood blocks. That’s where you got the charcoal off of them to make the briquettes.

Life in Parsons was not simply about industry. There are many wonderful stories about growing up in a peaceful community.

Mariwyn

McClain Smith recalls:

Mariwyn

McClain Smith recalls:

When I was growing up, my friends and I could be gone for hours, and nobody was the least bit concerned. I grew up one block from here, up on the hill. There was a hill behind it and hills on down in that direction. We spent hours and hours and hours on those hills, and nobody thought anything about it. We could ride our bikes for miles, even as small kids. It was pastureland, and you had to watch where you walked (laughs), but it was very steep hillside.

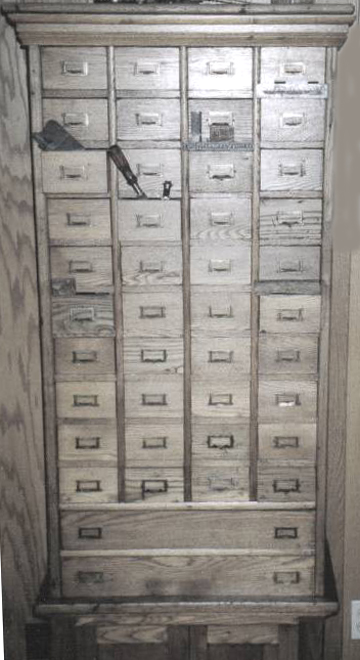

This bureau is from the days when the Parsons Advocate still used lined type. Each of those drawers held various letters or whole words to be set up each week to print the newspaper. This piece is also a survivor of the ‘85 flood, with some of the drawers having been replaced afterwards. Merywin Smith was long-time editor of the Parsons Advocate. Photo courtesy Merywin Smith

Steve Lambert has fond memories of fishing as a child:

I had an uncle that worked in Baltimore, Maryland, at a children’s home where they kept orphan children. He sent a guy from Baltimore to me when I was eight or nine years old. I was to take him to the section of the river in Parsons where I fished. I guess my uncle knew that I knew the river and the man wanted to go fishing.

He came from Baltimore to Parsons, West Virginia, to me, an eight-year-old fishing guide. And I took him fishing. As kids we weren’t real concerned about eating fish, just catching fish. The rock bass were just junk fish, really, fish to throw back and catch again. Well, this guy was keeping his fish. They weren’t that good to eat, you know, they were very bony. He had a fine time though, even with falling in the river.

He was a typical guy from the city, didn’t get out much—I could tell—even at eight or nine years old. He had real fine equipment that he’d bought just to spend the day on that river. I wore him out. I will never forget that. He had a good time. There was no limit on that kind of fish. I guess you could eat them rock bass but they were more trouble than they were worth because of the bones.

As a small boy living in Parsons, us kids would fish off the town bridge in Parsons, and there was a guy that always fished off the bridge named Calvin. I can’t think of his last name but anyone from Tucker County can. He never uttered a word, just fished. You could never talk to him because he wouldn’t talk back. He was a great big guy with crossed eyes. Us kids had a kind of a joke going around that you couldn’t steal the worms out of his can because he could watch his line with one eye and his can of worms with the other.

When I was a kid, Parsons was a very nice community. You

didn’t lock your doors

at

night. You didn’t take your keys out of your car, nothing like that. You don’t

do that anymore. I can remember swimming in the Shavers Fork every day, I

remember fishing every day. We had the Peterson hole where we swum. That

disappeared in the ’85 flood.—Jim Propst

at

night. You didn’t take your keys out of your car, nothing like that. You don’t

do that anymore. I can remember swimming in the Shavers Fork every day, I

remember fishing every day. We had the Peterson hole where we swum. That

disappeared in the ’85 flood.—Jim Propst

Jim Propst, who owns a grocery store in town, recalls Calvin as well:

Calvin Campbell. I remember him very well. He would go fishing for suckers and catfish: carry a big ole tub along with him and he’d get ten of them. He’d take them home and put them through the meat grinder and eat. If he only got one, he’d go home and eat it! Now Calvin went into the service the same time I did. Of course, he didn’t pass. He wanted to go real bad. But when they got to Fairmont for examination—it was in the summertime—he would not let them take his long underwear off to examine him. So, he didn’t pass.

Because of the Depression, which was not alleviated locally until World War II, many kids had to find small jobs to do to help bring money into the household.

Jim Phillips recalls:

I had to deliver milk. We had our own cow and our own livestock. A neighbor kept cows up there, and that was my first job—delivering milk for them because the guys were off in the military. I delivered in the morning and in the night. It was those old quart jars before they was homogenized and pasteurized. Big creamy top. Thick. These days they are very clean and careful with their milk.

I went over there and asked for the job. I went over there, and I said, “I hear that you need somebody to deliver the milk. I’d like to have the job.” It paid six dollars a month. Yeah. Big money. It was so many quarts in the morning and so many quarts at night.

The lady looked at me, and she said, “Jimmy, you’re awfully small and skinny. I don’t think you’ll be able to take care of those big quarts.”

And I says, “Oh, yes I can. I’ve got a little wagon. I’ll put the bottles in and pull it around to deliver the bottles in.” That’s how I made my money to go to the picture show with! (laughs)

-

The Parsons Hose Company’s old fire wagon from

1910. This fire wagon was used before the Parsons volunteer fire department

came around which was in 1932. It has since been repainted and fitted with new

wheels, and is being housed in the Tucker County Historical Societies office,

which is open on Sundays and by appointment. Photo courtesy Tucker County

Historical Society.

There were many people trying to figure out ways to make money. Hayward Phillips, Jim’s brother, tells about one venture where his father tried to make money:

Joseph was my father, and he cut ice. There was the Parsons Pulp & Paper Company, and when they were in business, he cut ice off the river, right where they were located. He opened up an ice business and did very well. We did very well in the Depression. I was a little kid then. When the refrigerator hit, that was ‘36 I think, that drove us out of business.

He told me that they used to cut ice as thick as eighteen inches. And then they’d haul it in this concrete building, and he’d put sawdust around it. And then the ice, and then he put the sawdust around the ice. It was great for him because he didn’t have any cost, and the product was free, so he did real well. All he had to do was put the labor in it. We lived very well from that ice but the refrigerator did us in. My Dad was always up to something but something always happened to him. He never could seem to make it.

But this ice that they took off the river, they used to take it off the Peterson Hole. I don’t know why it’s called Peterson hole, but you could make up a good story about it. I won’t make up a story, but you could say old man Peterson fell off a log there or something.

We used to go swimming up there all the time. Bob Weese used to take us up there. I have great memories of swimming at Peterson Hole. That was good clean water up above the city. Now we’ve got sewage all the way down to Holly Meadows.

My father did tell me quite a bit about the ice business. I used to help him. What I remember is that we’d go into these women’s houses, and they had an icebox where you stick the ice in here. And it drips down here to a pan, and it kept the food cold.

What I remember was the particular women, “Don’t you drop a drop of ice on my floor.” Of course, it was tight then, and people didn’t have any money: “Get that ice in as soon as you can.”

We’d weigh the ice on the back of the truck and then bring it in, so they wanted to get their money’s worth. They usually put in about fifteen pounds in an icebox. And they were particular about getting water on their floors and whatnot.

Yes, our home place is still up. It’s right next to the clinic. It had triple windows in it—it had to have windows so he could see the ice to cut it—but it’s still in there. I like to go by every once in a while, just for food for thought. I don’t remember how much he used to charge but back then a dollar a day was big wages.

In a 1989 interview, Londa Bennett recalls going to work at the nursery, which was established by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) to help reforest the Monongahela National Forest:

I’ll tell you how I got the job. I got sick. I had spots on my lungs, and my doctor told me to get out in the sun and stay out in it as much as I could.

A neighbor of mine worked there, and she said, “Why don’t you get on and work at the nursery? I’ll work with you and help you with the work.”

Mr. Oliver, he was our neighbor out there, so we talked to him. He said, “Come on out.” That’s the way I got started. He lived on Spruce Street. I forget what year he moved away. That is when I went to work there. I liked it, even when we waded or had to crawl in mud and sand to weed. The sun was so hot but we didn’t mind it. I liked it.

We had a good crew to work with. Mr. Oliver was a nice man to work for. He was very considerate about the people who worked for him. I have a funny little tale I might tell you about him. The sun had been so hot for a whole week, way up in the 80’s and 90’s. We were out in the field. We wanted to talk about seeing if we could get him to let us have part of our noon hour in the afternoon a little bit so we could get in the shade.

One of us said, “Why don’t one of us faint and then he’ll let us in a little bit?”

They drew straws, and, of course, I was the one that got the straw. When we came out that afternoon it was 85, and I started to get water. They kept the water way down at the end of the line. I was supposed to let on the faint but I didn’t let on, I really fainted. The crew didn’t know that I had fainted, and they were just so excited. Mrs. Oliver was a nurse. They saw me fall in the field, and they both came running. Then they took me home.

So the next day then when it was so hot, he would give us twenty, twenty-five minutes in the afternoon at 2 o’clock in out of the sun. I made them treat me too. He was a nice man.

Forest Service

In a 1989 interview, Harry Mahoney fills in a bit more information about Forest Service activities near Parsons:

When I was on the Cheat District, we had a relatively small staff. Part of the time I was there, most of our people were working in both the timber and the other resources. One assistant ranger couldn’t depend on having the same crew that we usually had that particular day so we had to coordinate things a little more. Generally, the people would get together in the warehouse where the vehicles and the tools are kept; get their assignment if they didn’t already have it; and gather up the equipment they needed for that particular job, usually in the field.

The District Ranger might or might not be present at that time. When I was ranger at Parsons it was during the period when the ranger station was not in the Nursery Bottom. It was downtown at the Post Office building. It had been in the Nursery Bottom but moved to the Post Office in 1966 and then back out into the Nursery Bottom in about 1983. While I was there, the ranger’s office was actually downtown. So frequently I would go directly to the office and make the assignments.

The feeling at the time was that the ranger’s office should be more accessible to the people in the community. They were building a new post office building in Parsons. The old office, which was last used as a nursery superintendent’s office, was too small. The District organization had grown to where that wasn’t an adequate facility. So while they were building the post office in Parsons, it was decided that they would like to move the ranger’s office in there. And they built a second story on it and put an office there. You had more space.

There was quite a bit of industry in Parsons at one time, but that time has passed. The wool mill shut down in ‘71, to be replaced by a shoe factory, which flooded in ‘85 and again in ‘96 and was forced to call it quits. Kingsford has been the only stable industry, having built a floodwall after the ‘85 flood. It is now the largest charcoal producing plant in the world.

The 1985 flood was the biggest loss for the town of Parsons. Many people had heard of the giant flood of 1888, where the waters reached 20.5 feet in Parsons. Fortunately, that flood did little damage since most of the houses were on higher ground then. The flood of 1985 crested at 24.3 feet (Long, 198), and the damage that it caused the town still reverberates.

The Flood of 1985

From a Special Edition of the Elkins InterMountain, November 22, 1985.

The following three passages are drawn from folklorist and oral historian Michael Kline’s taped interviews with survivors of the 1985 flood in Parsons. He first responded to the disaster by singing and playing his guitar at relief centers. When he realized he could be more helpful by just listening, he ask flood survivors to tell their stories. He taped one hundred hours of interviews, eventually distilling the stories down to a two-hour recording which wove people’s versions of the event together in a creative way. In addition, he used the material as his PhD dissertation in a written version entitled, “Hey, You Want To Talk About It?: Flood Narratives from a West Virginia Community.” He used a transcribing system called “narrative performance” which indicated both breathing patterns and silences. Kline explains, “Each line is the utterance of one breath. When the narrator pauses for breath the text moves to a new line. If the pause is a little longer than the usual breath, the silence is indicated by an indented dot.”

I’m past eighty-one years old and never seen nothing like this.

I don’t think we ever had anything like this.

This was

more water than what happened in 1888 as far as I can tell

because

they was marks

on trees

down the river there

.

the marks down there on the trees where them old fellows

showed me this was way higher than the 1888 flood.

- Ona Hovatter

Not many people in their lifetime have seen anything like this.

I mean when we went the next morning when we went up on top of

Blackman Flats

and looked down from I don’t know whose yard

and the whole town was under water.

.

You know there is just something like the world the world’s coming to an end.

- Keith Cordial

All of this rain came down thirteen and a half inches or whatever it was.

.

The ground got saturated and the hillsides which are really very fragile things around here they’ve got you know a few a few inches to a few feet of soil overlaying the bedrock of the mountains and when that all gets saturated it becomes very unstable

……

One [archaeological] site in particular at Seneca Rocks had some artifacts made by prehistoric Indian people on the surface that we collected

previous to the flood that have been dated at two thousand years ago or maybe even a little earlier than that between two and three thousand years ago.

.

what it suggests to me

is that the effects of the flood were unlike

the effects of any flood in the last two or three thousand years in that area.

Jan Brashler, archaeologist for the Monongahela National Forest

A few days after the flood Michael Kline had been asked to sing and play his guitar at relief centers in some of Parsons’ schools and gymnasiums.

He writes:

I’d never seen faces so devastated. Eyes were glazed in shock. It was as if the sounds of water still pounded in their ears while ghostly visions of the flood surged in all corners of the room. …. People sat with bowed heads poking listlessly at their food and whispering quietly among themselves. I sang my heart out anyway. …. I began to hear bits and pieces of stories all around me. I was aghast at what people were telling.…..

Stories of people reaching out to one another in the rising waters of central West Virginia on November 4 and 5 were initially buried by the shock of the disaster. Struggles in knee-deep mud and slime to dig out and get on with the recovery effort left little time for sharing grief. … Homeless families were scattered, taken in by friends and neighbors. Major roads, few enough to begin with in West Virginia, were gouged out for miles. Power and phone outages left some families isolated without medicine or drinking water for days on end. It took weeks to figure out where everyone was. …One evening nearly a month after the flood, I was singing an old Carter Family hymn, “Diamonds in the Rough,” when an elderly gentleman began to sing a high tenor on the chorus. His name was Ona Hovater, and when we finished singing together he began to tell me his story. He compared this flood with the one in 1888. As a child he remembered old people showing him highwater marks of that flood, the worst within community memory.

Ona Hovater agreed to have his story recorded, and with that, Michael Kline began his project. Some of the stories he recorded were that of a Tucker County deputy sheriff who, with an elderly couple and several firemen, had been trapped upstairs in a house which was buffeted by debris and vibrating off its foundation all night; an account of the sheriff and a trooper being washed off the approach to a bridge and their rescue by a couple who anchored a rope around their own waists; the risky boat rescue of a young woman hanging onto a treetop; and the following story told by Juanita Wampler. Wampler left work in downtown Parsons a little early on the afternoon of November 4th. It was raining hard. She went home and relaxed, had her dinner and played with her cat. First one, then a second neighbor came over to say they were going to spend the night with relatives on higher ground:

I said what’s going on and he said well (Click HERE for mp3 audio of Juanita Wampler's story - 9minutes))

the river is rising fast

but he said I think that you are okay where you are

I think it will just be

you know

water in the grass

.

and I said well that’s

okay and the basement might get flooded so I’ll just bring up the paint…I was

going to paint the inside

of the house and .

just as I finished bringing them up

and I closed the basement door

it was like a blast

.

like a bomb had hit the house

and

that was when the basement wall caved in.

It even opened the door that I had just locked.

And the water was coming you know

then into the floor

from the basement

and I

put everything in the suitcase and everything out on the porch

I had seen the firetruck coming down

but

anyway I yelled for the firemen you know please help me

and

they yelled back and said well just hold on because there is a boat coming

so I stayed on the porch for a little while but then the water was rising there so

.

I went back into the house I opened the door and boy the water just gushed out so

.

and I got a chair these were heavy iron chairs I had in the dining room

I got one of those chairs and sat by the door on it so that I could hold the door open

to let the water pass out from the basement

and

it the house started to move then

and when it when I felt that it was starting to move

why

I

quick took my purse and put it in the closet and jammed clothes around it because I thought well those are important papers in there and maybe I will find them together which I never did

.

but

.

I let the door go

and

by this time the

water was up to my chin while I was sitting there

so I let the door go and I

I sort of

.

swam almost to the dining room and got a barstool

.,..

but

while I was sitting on the barstool and you know how high they are

.

the water was getting up to about here and I then saw the ceiling starting to collapse

I wanted you know to be knocked out

and

of course I wasn’t

but as it started to fall I took the cat in her case and just threw her into the water I figured well at least she would drown right away

but

.

.

when the ceiling came down

I felt like I was drowning

.

and I kept fighting it and finally I just said uh uh

.

you might as well drown and get it over with

.

so I just opened my mouth and just

breathed in the water

.

and then the next thing I knew

it was like

a big wave threw me out

and I was

I grabbed hold of these trees.

.

When I was standing there and holding on

.

I said to myself

this is a stupid place for a woman your age to be

.

oh boy

.

I thought

gosh I am going to get a sinus headache out here.

.

It’s strange the things you think about you know

and

then I said hmm hypothermia

well I better keep moving

.

so I just tried to keep moving you know and they told me later that I had rubbed all the bark off of one of the trees

and

.

the debris kept hitting me and I didn’t mind because

.

it did help to keep me warm

it really did.

It was a good thing I had my coat on

and oh I had put on a white coat

when I thought I was going to be rescued

because I thought

well that will show up

.

and

of course it got

dirty from the flood

so they couldn’t even see me hardly until they got about ten feet away from me when they rescued me.

But during the night

it started to rain

and

a globe

from a

a light you know a ceiling fixture

passed

by so I just grabbed hold of it and put it on my head because I had lost my hat see

when the ceiling caved in

.

and

that helped keep my head warm for a little while

and my chest was cold because this coat didn‘t have buttons on it see

and

I am very susceptible to colds having bronchitis and asthma and ev- that was another thing I thought oh boy I will have an asthma attack out here

.

but

I grabbed a piece of Styrofoam

and I know it was one that I had had down the basement that I was going to use for insulation down there

and I grabbed that and put it up under my blouse

and that helped to keep me warm.

And

then I saw all these lights

over on the Moss Bridge Road

and I thought that they were coming to rescue me

.

and that was when they were rescuing Amy.

.

And oh boy I really had hope then you know

but then when they went away boy I never felt so alone in all my life.

.

But

at one point I said well if I can last out the night somebody will find me and they did.

.

When dawn came and

I started to see people you know come down

to the water’s edge

which was still like a big lake

.

and I started yelling and this

girl heard me and

found these couple of men and

they waded in.

They even held hands because they didn‘t know what they were going to fall into you know

.

so then

they said

well we will carry you out I said oh no I’m too heavy to carry out I said just walk me out I said and my legs need to be walked so

we would walk three or four steps and stop

and

finally got up to his house

and

.

his wife just took all of my clothes off and put me in a warm suit that she had.

They didn’t have any electricity

but they did have a fireplace

.

and

she said can I give you something to drink? We re- we don’t have any

thing hot

.

and all I could think of was

gee I’d like to have a glass of brandy or a glass of wine that would really warm me

and they happened to be

teetotalers

so

she gave me a glass of cold milk.

Click HERE for mp3 audio of the rest of Michael Kline's interviews. (90 minutes)

Many of those Michael Kline interviewed spoke about how the flood brought Parsons people closer together, having experienced everyone helping each other out during that devastating night and the following days. Linda Rhodes expressed it this way:

And it’s true that the flood did bring people together

it did

it brought us closer to the people around us

and it makes you realize the things that’s not important to you

like the stuff you spend money on that you think you have to have

to be in or whatever you want but it

that stuff don’t really matter to a person

when you almost lost your family

.

being happy and just having a

a place to live and a roof over your head and being with the people that you love

that’s the only thing that really matters

.

because if you don’t have that well then

materials aren’t going

to make up for it.

Jim Propst explained to me one of the lasting effects of the flood:

Parsons, after the flood of ‘85, never did come back like it should’ve. Then we had a bad fire on Front Street, took two-three houses out. Then FEMA [Federal Emergency Management Agency] come through and bought the houses in the flood zone. So the city has all these empty lots you’re not allowed to build on.

Everybody says, “Well, lets get industry here.” So where would you put it if you got it here? It’s in the flood zone mostly, and there’s no place for anybody to live. And it’s much slower. Parsons doesn’t have near the population that it did then.

Parsons used to have a theatre, which it doesn’t have anymore. When I came back from the service and first went into the grocery business—we had a little Mom and Pop store on every corner—and we all worked so good together. Two or three of us would take a truck and go get groceries for all of us. If I run out, I’d borrow off them or they’d borrow off me. They don’t do that kind of stuff today.

Small groups formed to try to help the community. The famous “Cookie Ladies” did grassroots work and raised money to establish a floodwall in the town.

Mariwyn Smith tells about another group:

The worst problem is the block of buildings on First Street where there is little to no business. Ben Long has his store up there. And then Eddie McDonald built the building down at the end of the block, and that’s where the video store is.

There is a group of men and women who call themselves PRO—Parsons Reclamation Organization. They hope to get enough money to buy that whole block and put in a parking garage on the first floor with offices or apartments or something of that sort above it, because the law will not allow us to build anything that will hold back water in the flood area.

The future of Parsons remains to be seen. While some small industry is moving into the town, many fear that the town will slowly disappear.

Alice and Jim Phillips share:

Alice: Private little businesses are setting up in there, which might help, even if it is only five or ten people to start out with, it’s good.

Jim: Parsons never recovered from the flood and probably never will. Down there, there are a bunch of vacant buildings. As you come up main street, you think those buildings . . . That one big building there right next to the courthouse, the roof’s all caved in from snow last year.

Alice: Farther down, there are three buildings there where the fronts are there, but they burned out from the inside. They can’t dismantle them because they found that they interlocked with other buildings that are still standing. I don’t know what they’re going to do. It used to be a beautiful little town, a thriving little town.

We had the woolen mill, the tannery—Hinchcliff [Lumber Company] was here—the handle factory, the Forest Service. Front Street, they had an H&P store. And then Mr. Tootharden, who was the manager, after the H&P closed, he opened up his own little business. It was merchandise like J.C. Penny handles. He was doing well until the flood of ‘85. He tried to come back, but people were mall hopping.

Parsons may go the way of Spruce or it may find a second life. Only the future will tell. But like the rest of the watershed, Parsons is filled with stories that not only flesh out the history of the area but provide insight into what life was like in the twentieth century.

Shortly after the first land battle of the Civil War in Phillipi, West Virginia, another battle took place on the lower section of Shavers Fork, just above Parsons at a site known as Corrick’s Ford. L.D. Corrick was a homesteader there and the shallow part of the river, divided by an island, soon came to be known as Corrick’s Ford.

After the Confederate forces were forced to withdraw from Phillipi, they tried to re-group and keep the Staunton-Parkersburg Turnpike from the Union troops. However, the Union army tried to cut off the Confederate troops’ escape by attacking from both sides of the road.

The Confederate army, led by Brigadier General Robert S. Garnett, began a hasty retreat under cover of darkness. In their haste, the Confederates were forced to abandon much of their equipment. After an extended chase in pouring rain, the Union troops, led by Major General George B. McClellan, (who, less than four months later was named General-in-Chief) caught up to Garnett’s troops. Skirmishes ensued, with no serious losses by either side.

The Confederates again tried to retreat. Seeing a good spot to place a ten-sniper regiment, Garnett paused to select and place soldiers. As he did, the Union army approached. A shot nicked General Garnett’s horse, and as he turned to leave the battleground, Garnett was shot in the back and killed. His body was abandoned and the Union army rafted his remains to Rowlesburg, and from there to Wheeling for burial. Garnett was the first high ranking officer to die in the Civil War.

Discovery of the body of General Garnett by Major J.W. Gordon and Colonel E. Dumont after the Battle of Corricks Ford. From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Photo courtesy Hunter Lesser.