Chapter

2

“Come

into the light of things. Let nature be your

teacher.”

William Wordsworth

The Setting:

An

Ecological Glimpse of the Shavers Fork Watershed

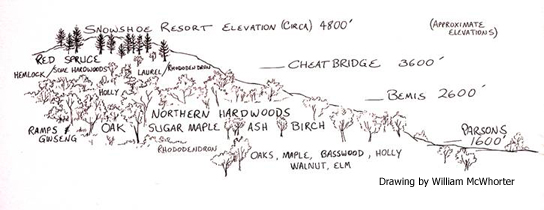

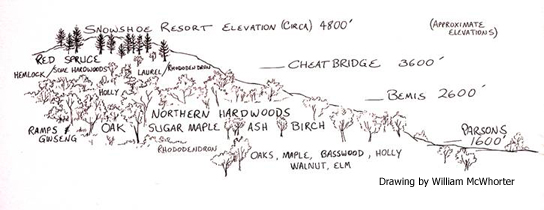

Stories in this book describe vast wild areas

and great forests. Following are short descriptions of the various habitats

found in the Shavers Fork watershed. While the areas tend to occur as layers as

one travels downhill from the highest points at Snowshoe and Bald Knob, many

exceptions exist. East- and west-facing slopes and water drainage patterns are

major factors. Millions of influences determine which species will live in any

particular area; however, general rules apply.

A Brief Ecological History

Shavers Fork has been forming since the

continental plates first began their slow, inevitable drift. Approximately 500

million years ago, what are now Africa and North America collided, forming the

Appalachian Mountains. Since then, the Appalachians have undergone three cycles

of buildup and erosion.

In the last two million years, Cheat Mountain

has experienced approximately eighteen to twenty glacier cycles (Constanz, 14).

While glaciers did not cover Cheat Mountain, they acutely impacted its climate.

Giant animals like short-faced bears (larger than modern grizzlies), huge

camels, two species of elephants, mastodons, mammoths, saber-toothed cats,

American lions, and huge dire wolves ruled the landscape until humans appeared

approximately 12,000 years ago.

The flora and fauna have undergone drastic

changes. When the Appalachians first formed, there were none of the trees and

laurel thickets prevalent today—these had not yet evolved. Mountains were

covered with primitive seed ferns, tree club mosses, and giant horsetails up to

sixty feet tall. These plants still exist, but as dwarf species. Modern

horsetails are often only two feet tall (Weidensaul, 12, 14). Later, animals and

insects populated the area.

The flora and fauna have undergone drastic

changes. When the Appalachians first formed, there were none of the trees and

laurel thickets prevalent today—these had not yet evolved. Mountains were

covered with primitive seed ferns, tree club mosses, and giant horsetails up to

sixty feet tall. These plants still exist, but as dwarf species. Modern

horsetails are often only two feet tall (Weidensaul, 12, 14). Later, animals and

insects populated the area.

As these glaciers retreated northward,

organisms dispersed with them. Boreal forest replaced tundra, then mixed

hardwoods, and then even more southern organisms. Some species became stranded

on mountains as the warmer climate moved in and broke up the forest. As the

weather continued to warm, the only place to find colder weather was at higher

elevations, separating species in the mountains. However, a mountain only goes

up so far, and some species literally climbed to extinction, at least locally.

View to the south (upstream) with Greenbrier Junction in lower center.

Photo courtesy

Zach Henderson

Shavers Fork Journey

The Shavers Fork is the highest river of its

size east of the Mississippi.

The watershed’s highest point is the top of Bald

Knob, 4,860 feet. A drop of rain that falls on Bald Knob cascades down roughly

eighty-four stream miles before it reaches Parsons. Over the course of its

journey, the river drops more than 3,200 feet, almost double the drop over the

rest of the 3,000-some odd mile journey through the Cheat, Monongahela, Ohio,

and Mississippi rivers before reaching the Gulf of Mexico (Brooks, 263).

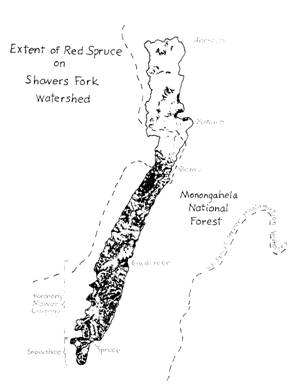

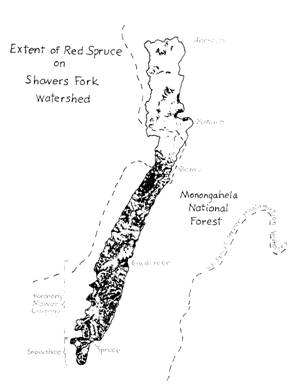

Red Spruce

The top of Cheat Mountain hosts an ecosystem

rare in West Virginia, although it is anything but rare in more northern parts

of the continent. As the massive Wisconsin glacier retreated north 10,000 years

ago, the red spruce ecosystem followed. However, in West Virginia, some spruce

stands migrated up mountains and became stranded from the rest of the northward

movement. Such was the case on Cheat Mountain, which includes eight of the

highest points in the state. Here the elevation provided red spruce with the

cold environment it needs.

Cheat Mountain’s precipitation offered the red

spruce another advantage. The top of Cheat Mountain is the second wettest area

in the state. Snowshoe Mountain Resort records more than fifty-six inches of

precipitation per year and an average temperature of forty-three degrees

(Stevenson, 7). This rain and snow create a climate that cools more than the

elevation alone does.

Red spruce (Picea rubens), defines the

forest atop Cheat Mountain. Rolling a needle in your fingers reveals the classic

characteristics of spruce: short, stiff, sharp needles with squared edges. Like

other conifers, it produces cones that are reddish with small seeds. If seed

predators, like the red squirrel do not eat them, the seeds will likely produce

the next generation of red spruce.

Before drastic ecological changes occurred as

European settlers migrated to the region in the late eighteenth and early

nineteenth centuries, spruce stands extended down to 2,000 feet in elevation.

Changes in the ecosystem and intensive logging now limit stands to sites above

2,500 feet, and then the red spruce only thrive in wet, cold locations (Core,

35).

The condition of the original forest was lost

to intensive logging, which began around the turn of the nineteenth century.

Through anecdotal evidence, we have glimpses of what the forests were once like;

but there is virtually no scientific research from that time. In 1891, the

spruce forest in West Virginia was estimated at 469,000 acres with 140,500 acres

in Randolph County and 70,000 in Pocahontas (Brooks, 373, 374). The cutting

didn’t stop there. By 1910, less than twenty years later, the red spruce forest

area had declined to 190,000 acres—80,000 in Randolph and 70,000 in Pocahontas.

The condition of the original forest was lost

to intensive logging, which began around the turn of the nineteenth century.

Through anecdotal evidence, we have glimpses of what the forests were once like;

but there is virtually no scientific research from that time. In 1891, the

spruce forest in West Virginia was estimated at 469,000 acres with 140,500 acres

in Randolph County and 70,000 in Pocahontas (Brooks, 373, 374). The cutting

didn’t stop there. By 1910, less than twenty years later, the red spruce forest

area had declined to 190,000 acres—80,000 in Randolph and 70,000 in Pocahontas.

Ambrose Bierce, who lived on top of Cheat

Mountain at Fort Milroy in the winter of 1861–1862, provided one of the best

descriptions. Bierce compared the spruce forests to a dark pelt upon the

mountains—the legs of the pelt descending to lower reaches where conditions were

favorable.

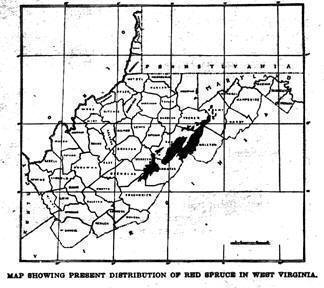

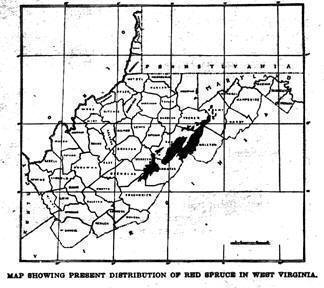

Map showing distribution of Red Spruce in West

Virginia in 1911.

From A.B. Brooks’ survey published that year for the West

Virginia Agriculture Department.

Today, the forests may be close to 100 percent

spruce in the highest reaches. At lower elevations spruce trees mix with other

tree species, including, in order of decreasing abundance: yellow birch,

American beech, black cherry, red maple, striped maple, cucumber magnolia,

mountain magnolia, and yellow poplar (Stephenson, 27). The trees, while being

physically very large, do not determine all aspects of the forest. In fact,

trees often are found at a certain location because of help of other organisms.

Red spruce thrives in sites with a cold, wet climate and poor soil. Byzzania

moss helps to create this environment and needs the shade red spruce trees

provide. Symbiotic relationships like these, as well as other interactions,

yield a multitude of environments that support a wide variety of plant and

animal species.

The Cheat Mountain climate maintains many

niches and environments that support an array of flora and fauna. Because the

climate is so drastically different from the top of Cheat Mountain to the

valleys, many species have been isolated here for thousands of years. Because

of this isolation, populations would only breed with others on the mountain,

creating genetic variations and serving to create numerous isolated populations

of species that are normally found much further north. The Cheat Mountain

salamander, the West Virginia northern flying squirrel, and running buffalo

clover are examples of these locally rare and endangered species.

Mountain Swamps

Numerous swamps and bogs are sprinkled among

the red spruce forests. While it may seem peculiar for mountains to have

wetlands, most do, and such areas are vital to many species. These wetlands

exist as small isolated pockets no larger than 250 acres in size, making them

small oases within the island in the sky that Cheat Mountain forms. Stands of

red spruce usually surround these wetlands, thriving in the wet, cool climate

and rich peat soil that the wetlands have produced.

Numerous swamps and bogs are sprinkled among

the red spruce forests. While it may seem peculiar for mountains to have

wetlands, most do, and such areas are vital to many species. These wetlands

exist as small isolated pockets no larger than 250 acres in size, making them

small oases within the island in the sky that Cheat Mountain forms. Stands of

red spruce usually surround these wetlands, thriving in the wet, cool climate

and rich peat soil that the wetlands have produced.

Perhaps the best example of a high-elevation

wetland ecosystem is Blister Swamp, near Gaudineer Knob and named after the

balsam fir trees that grow in the area. Balsam firs are also called blister pine

because of the small pockets of resin on its trunk. These small pouches look and

feel like blisters on a person’s skin. When pinched, they pop, spraying a sticky

resin that is very hard to remove. Blister Swamp is one of the two southern-most

stands of balsam fir – it was named a national landmark in 1974. For the last

several years, a small insect called the balsam fir wooly adelgid has killed

many trees in this stand.

Beaver dam built in a bog on Cheat

Mountain. Courtesy The Nature Conservancy.

Mountain wetlands play a very important role

in maintaining a cool climate, as they trap the moist air. Thus, the swamps help

maintain the cool climate needed by red spruce trees. These wetlands also

provide a unique habitat for many plants and animals, such as beavers, which

actually create and maintain of some of these wetland areas.

Scour Zone

Another habitat along the upper reaches of the

Shavers Fork provides home to several rare species. Large blocks of ice form on

the surfaces of the streams during the winter. On warm days, the water rises

above the ice and becomes trapped, later freezing and enlarging the ice sheet

beyond the stream banks. As spring approaches, the ice melts and these sheets

shift and destabilize, scouring the stream banks. Annual scour prevents woody

plants from establishing themselves. This bare ground provides habitat for

herbaceous perennials, which die back each fall, except for their roots,

anchored in the rocks. This zone also makes for easy shore fishing. In well-used

areas, such as around Cheat Bridge, the heavy foot traffic can destroy these

plants.

around Cheat Bridge, the heavy foot traffic can destroy these

plants.

Sticky false asphodel (Tofieldia glutinosa) is an example of a species

that thrives in this scour zone and exists nowhere else in West Virginia but on

Cheat Mountain. An herbaceous perennial lily, it was first identified close to

the old town of Spruce, near the headwaters of Shavers Fork. Like many lilies,

it has narrow strap-like leaves that arise from the base of the plant. The

fourteen-inch tall flowering stalk is topped with one-quarter-inch broad white

or greenish flowers that appear in midsummer. Glutinosa is Latin for

sticky, referring to the stalk’s gluey feel. Like many other denizens of Cheat

Mountain, sticky false asphodel also occurs in Canada, Alaska, and the northern

U.S. It also can be found in the higher mountains of West Virginia, Georgia, and

North Carolina (Stephenson, 69).

Ice scouring river bottom and

banks, March 2004. Photo courtesy Ruth Blackwell Rogers.

Northern Hardwoods

Descending Cheat Mountain, there are fewer red

spruce and associated species, and the landscape gradually transforms into a

northern hardwood forest. Sugar maple, beech, and yellow birch dominate this

system, although hemlock, basswood, red maple, white ash, black cherry, black

birch, cucumber tree, yellow poplar, red oak, and chestnut oak are usually

present and occasionally co-dominant (Stephenson, 16). In some areas, these tree

species have outpaced the red spruce after logging, so they are likely more

widespread today than they once were. Like the red spruce, these, too, normally

exist farther north. In West Virginia, the northern hardwoods grow in a narrow

altitude band between 2,800 and 3,600 feet; exceptions occur when conditions are

right.

If healthy, the northern hardwood forest has

five distinct horizontal layers. The first, the canopy layer, is the uppermost

foliage of the tallest trees. The sub-canopy layer, mostly younger trees of the

same species and species of trees that do not grow as high as the canopy layer,

includes trees like mountain holly and striped maple. The third layer is

composed primarily of woody shrubs and bushes like rhododendron, laurel, and red

elderberry. These species do not develop a single trunk, but branch out close to

the ground.

Herbaceous plants, such as spring wild

flowers, ramps, and ginseng, make up the fourth layer; they flower in the spring

because there is more light available before the trees leaf out. Bryophytes,

including hornworts, liverworts, mosses, and lichens, make up the bottommost

layer and play an important role in recycling decaying matter (Stephenson, 20,

21).

Oaks and

Caves

Below 2,800 feet, an oak hardwood community

covers a large part of the remaining Shavers Fork watershed. This ecosystem,

although similar to the northern hardwoods, the oak forest features some

significant differences. It includes sugar maple, white ash, American basswood,

and yellow birch, intermixed with and often dominated by various oak species,

giving the system its name.

In these lower mountain areas, various

sediment layers may be exposed. Limestone is more common, creating caves, with

many in the Bowden area. Some caves once sheltered Native Americans. These now

entertain spelunkers, with some of the most complex, offering several miles of

navigable trails. Several caves have been closed because of concern that their

ceilings may collapse.

These caves are home to the Indiana bat (Myotis

sodalis). While West Virginia is at the eastern edge of this bat’s range,

more than 10,000 hibernate here. With a wingspan of ten inches, the Indiana bat

weighs about as much as a house key. They are social animals, living in colonies

both during the winter and the summer; with the summer colonies divided by sex.

In winter, hibernation colonies are large and compact, with densities reaching

300 bats per square foot. This arrangement allows an individual bat to benefit

from the heat of nearby bats, lowering the energy it uses to keep warm.

Due to a drastic decline in numbers, the

Indiana bat has been named a threatened and endangered species. The causes of

decline are not yet understood. One possible reason is loss of habitat in the

Midwest since many forests are now gone. Another possibility is winter

disturbance by cavers. The bat stores fat during summer and fall months to

endure a long hibernation. Every time the bat wakes up from a disturbance, it

wastes valuable fat stores, leading to slow, painful death by starvation (West

Virginia Department of Natural Resources fact sheet).

Rocks and Geology

Rocks and Geology

Rocks surrounding the Shavers Fork determine

its stream pattern. Differences in

how easily eroded one rock type is over

another have

created many of the bends and turns in the river. Shale and

sandstone are the two primary rock types, with coal seams and limestone present.

This relative dearth of limestone and other high pH rocks make the Shavers Fork

naturally slightly acidic, and it can tolerate very little additional acid

deposited from precipitation.

The shale and coal formed over thousands of

years as dead organic matter created peat, a dark, rich, oxygen-poor yet

flammable material. Over time, the peat turned into coal or shale, depending on

numerous factors.

The author at center right looking at High

Falls of Cheat. Photo courtesy Vicki Chapin.

Aquatic Life

The

headwaters and small tributaries of the Shavers Fork support sculpins, black

nose dace, darters and several other species of small fish. Creek chubs and

darters swim in the larger channel. The mainstem also hosts the Cheat minnow,

which may be a unique species of fish or simply an interesting hybrid. The

sought-after brook trout runs throughout these waters.

The upper reaches of the Shavers Fork host

native populations of brook trout. Unlike other fish, brook trout, which

fishermen often call “brookies,” tolerate fairly acidic water. At higher

elevations, there is not much limestone to buffer the stream, and the red spruce

creates a slightly acidic environment for the water as it drains through the

soil. While brookies and other fish species may tolerate this natural level of

acidity, new acidic input from acid deposition threatens the species in the

river.

Threats

to the Watershed

The red spruce ecosystem on Cheat Mountain is

particularly susceptible to global warming. A five-degree rise in average

temperature could eliminate red spruce and its associated species from Cheat

Mountain. Global warming is a tough problem because it has no single cause. Many

daily human activities, like driving cars and heating homes, add to global

warming.

As previously mentioned, pH levels of the

river are also precarious. Surprisingly, the water from local mines is not the

source; the primary problem comes from the clouds in the form of acid deposition

commonly called acid rain. Since Cheat Mountain is often cloaked in clouds,

which tend to have a lower pH than rain, acid arrives in more ways than just

rain. Pollution from the Midwest floats eastward until it hits Cheat Mountain,

dropping as rain or snow as it climbs over the mountain to continue eastward.

There have been attempts to correct this

acidity, such as dumping ground limestone near small streams to help alkalize

the acidic water. Acid precipitation still creates problems. One impact acid

rain has on trees is that it breaks down the leaves’ outer waxy layer, making

the trees more susceptible to infection. Red spruce trees seem especially

vulnerable to acid precipitation, which may underlie the marked decline in red

spruce trees of all ages in recent times (Stephenson, 261–265).

In certain areas, old trees are dying

prematurely. While young trees continue to replace the old, size diversity is

important to associated species. Perhaps the most troubling aspect of acid

precipitation is that there are no signs of improvement, and there probably will

not be until efforts address the sources of the problem and not just the

symptoms.

The final threat considered here is invasive

plant species, which are slowly moving up the watershed toward the top of Cheat

Mountain. These species are able to out-compete an area and can completely choke

out other plants. Ferns are a prime example, and it is no longer difficult to

find fern-covered forest ground.

Wildlife

One major impact of the turn-of-the 20th

century clearcut was decimation of the deer population. Whitetails almost

disappeared in  the early 1900s. A small herd survived on the top of Cheat

Mountain. In 1909 a series of laws were passed prohibiting the sale and shipment

of game outside of West Virginia. These laws were in effect until 1921, when

game wardens were hired and a deer-hunting season was established. In 1930, the

population of deer in the Monongahela National Forest was estimated to be only

thirty deer (Berman, 74). By 1945, the population had completely rebounded and

deer were considered pests in some areas.

the early 1900s. A small herd survived on the top of Cheat

Mountain. In 1909 a series of laws were passed prohibiting the sale and shipment

of game outside of West Virginia. These laws were in effect until 1921, when

game wardens were hired and a deer-hunting season was established. In 1930, the

population of deer in the Monongahela National Forest was estimated to be only

thirty deer (Berman, 74). By 1945, the population had completely rebounded and

deer were considered pests in some areas.

Black bears were almost wiped out because they

were considered an enemy of people. Many counties placed a bounty on the

animals, hoping to be rid of the nuisance. If they had a little more time, they

might have been successful. West Virginia’s bear population was reduced to

approximately 500 bears at one point; but the general perception of the animal

began to change. The black bear was named the state mammal in 1955, although

Pocahontas County’s bounty remained in effect until 1969 (Stephenson, 219). Now

black bear thrive in West Virginia and maintain a stable population.

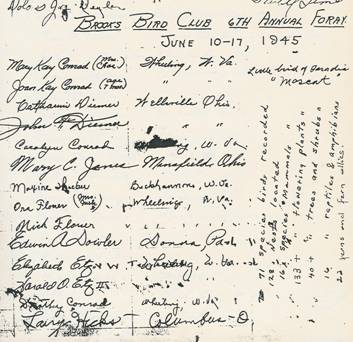

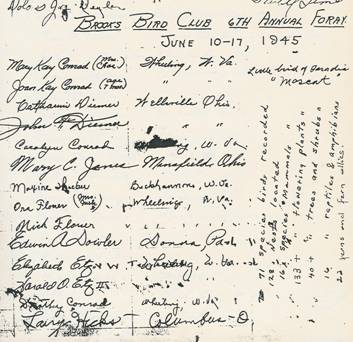

Entry in Cheat Mountain Club logbook listing

species of birds, plants, and animals found during the Brooks Bird Club Annual

Foray. Photo by Matthew Branch.

Other species have followed a similar pattern.

Turkeys once almost vanished from West Virginia, but due to a change in

management practices, and a little bit of luck (many early attempts at

increasing the population failed), the turkey population is thriving. Other

species were not so lucky. Woodland bison (Bison bison) were the first to

disappear; the last one was killed near the headwaters of the Shavers Fork in

1825. Then elk (Cervus elaphus) were hunted to extinction. The last elk

was shot in 1890. The last grey wolf was killed in 1900, although coyotes

probably now fill their ecological niche. By 1923, beavers (Castor

canadensis) were hunted and trapped to extinction because of their sought

after pelts. However, they were reintroduced between 1933 and 1940 and have

since made a spectacular comeback (Stephenson, 216, 219–221).

Link to Chapter Three

The flora and fauna have undergone drastic

changes. When the Appalachians first formed, there were none of the trees and

laurel thickets prevalent today—these had not yet evolved. Mountains were

covered with primitive seed ferns, tree club mosses, and giant horsetails up to

sixty feet tall. These plants still exist, but as dwarf species. Modern

horsetails are often only two feet tall (Weidensaul, 12, 14). Later, animals and

insects populated the area.

The flora and fauna have undergone drastic

changes. When the Appalachians first formed, there were none of the trees and

laurel thickets prevalent today—these had not yet evolved. Mountains were

covered with primitive seed ferns, tree club mosses, and giant horsetails up to

sixty feet tall. These plants still exist, but as dwarf species. Modern

horsetails are often only two feet tall (Weidensaul, 12, 14). Later, animals and

insects populated the area. The condition of the original forest was lost

to intensive logging, which began around the turn of the nineteenth century.

Through anecdotal evidence, we have glimpses of what the forests were once like;

but there is virtually no scientific research from that time. In 1891, the

spruce forest in West Virginia was estimated at 469,000 acres with 140,500 acres

in Randolph County and 70,000 in Pocahontas (Brooks, 373, 374). The cutting

didn’t stop there. By 1910, less than twenty years later, the red spruce forest

area had declined to 190,000 acres—80,000 in Randolph and 70,000 in Pocahontas.

The condition of the original forest was lost

to intensive logging, which began around the turn of the nineteenth century.

Through anecdotal evidence, we have glimpses of what the forests were once like;

but there is virtually no scientific research from that time. In 1891, the

spruce forest in West Virginia was estimated at 469,000 acres with 140,500 acres

in Randolph County and 70,000 in Pocahontas (Brooks, 373, 374). The cutting

didn’t stop there. By 1910, less than twenty years later, the red spruce forest

area had declined to 190,000 acres—80,000 in Randolph and 70,000 in Pocahontas.

Numerous swamps and bogs are sprinkled among

the red spruce forests. While it may seem peculiar for mountains to have

wetlands, most do, and such areas are vital to many species. These wetlands

exist as small isolated pockets no larger than 250 acres in size, making them

small oases within the island in the sky that Cheat Mountain forms. Stands of

red spruce usually surround these wetlands, thriving in the wet, cool climate

and rich peat soil that the wetlands have produced.

Numerous swamps and bogs are sprinkled among

the red spruce forests. While it may seem peculiar for mountains to have

wetlands, most do, and such areas are vital to many species. These wetlands

exist as small isolated pockets no larger than 250 acres in size, making them

small oases within the island in the sky that Cheat Mountain forms. Stands of

red spruce usually surround these wetlands, thriving in the wet, cool climate

and rich peat soil that the wetlands have produced. around Cheat Bridge, the heavy foot traffic can destroy these

plants.

around Cheat Bridge, the heavy foot traffic can destroy these

plants.

the early 1900s. A small herd survived on the top of Cheat

Mountain. In 1909 a series of laws were passed prohibiting the sale and shipment

of game outside of West Virginia. These laws were in effect until 1921, when

game wardens were hired and a deer-hunting season was established. In 1930, the

population of deer in the Monongahela National Forest was estimated to be only

thirty deer (Berman, 74). By 1945, the population had completely rebounded and

deer were considered pests in some areas.

the early 1900s. A small herd survived on the top of Cheat

Mountain. In 1909 a series of laws were passed prohibiting the sale and shipment

of game outside of West Virginia. These laws were in effect until 1921, when

game wardens were hired and a deer-hunting season was established. In 1930, the

population of deer in the Monongahela National Forest was estimated to be only

thirty deer (Berman, 74). By 1945, the population had completely rebounded and

deer were considered pests in some areas.