Grace:

There were two boys who come to school, and me and Marvin was doing janitor

work, we got $6 a month for sweeping and cleaning the school in the evening.

Grace:

There were two boys who come to school, and me and Marvin was doing janitor

work, we got $6 a month for sweeping and cleaning the school in the evening.“Where else can I be any happier than I am now?”

— Alice Cooper, Bemis resident

As the Shavers Fork reaches Bowden it flattens out and becomes wider; the river begins to meander. Thousands of years of flooding left a swath of fertile flat land on either side of its banks. This lower stretch is where the first pioneers settled on the Shavers. Here they carved small farms out of the vast Appalachian forest. The Monongahela National Forest has converted many of these farms back to woods.

Perhaps farming on the Shavers Fork will soon be lost but what memories it produced. Of all the interviews I conducted for the book, the farming stories had a special quality. It was something about the way people talked about their time there on the land with a wistful, happy look.

Hazel Phillips and Grace Gainer, both formerly Shaffers, grew up in the 1920’s and 1930’s on a farm by Shavers Fork near Nail Run, about eight miles upstream of Parsons. They shared many short stories, many memories:

Grace: If we wanted to go somewhere and Mom didn’t want us to go, she’d say, “Go ask your Dad.” And Dad . . . we didn’t question that. If he said no, we didn’t question that. But they had parties up there. They drank and they had lots of problems but we were young and we didn’t know about all that. Every fella [of the ten Shaffer children] had a job: one brought in water; one brought in kindling wood; one brought in coal; one washed dishes; one went to the mill; one fed the pigs; one fed the chickens. We all had a job. It was usually about the same thing every time.

Hazel: I washed dishes. I never minded them. My sister, who was two years older than I am, she hated washing dishes so I washed dishes rather than go milk. She’d milk in the morning and evening, but for lunch she didn’t think she had to help me do dishes. We bucked and we had trouble. We all fought. We hassled each other, but if someone else came in and touched any one of us, he better be on his way out. ‘Cause he was going get it from the rest of us.

Grace:

There were two boys who come to school, and me and Marvin was doing janitor

work, we got $6 a month for sweeping and cleaning the school in the evening.

Grace:

There were two boys who come to school, and me and Marvin was doing janitor

work, we got $6 a month for sweeping and cleaning the school in the evening.

Hazel: And building a fire.

Grace: Yeah. And these two boys come out there, and they said they was gonna whoop my brother. Me and Marvin, we went ahead—we did the sweeping and we did what we were supposed to do—and when we come out, they was up on the road waiting for us.

I said, “OK, you whip Marvin and I’ll whip the other one.”

We walked all the way home and no one touched either one of us because I was a hitter. I hit better than the boys

Hazel: My brother—there was ten of us and, of course, neighbors—but my brother, he was the oldest of us, and in the wintertime we had a horse sled; it was eight or ten feet long. Two horses would pull it. But there was enough of us that we could pull it up these hills and we’d pull it up the hills and he had a stick that was open on one end. He’d take that stick and guide it and we’d go almost a half a mile down two hills on that sled just flying, but there was enough of us we could pull it.

We made our own entertainment. We didn’t have a toy. We didn’t know what it was to have a toy. We’d go and cut forked sticks and make stilts. We would saw logs and make wheels for a wagon and we’d have a wagon. And we fished a lot. Mother never spanked. They never hit you but we had all kinds of little willow switches, and that’s what Mother used when we got out of control.

Grace: That hurt.

Hazel: When she said no, you knew better than to disobey. Our oldest brother, I mean, he was an ornery one. He loved to do things to excite someone. We had a family that lived across the river from the cemetery. And he had made him a panther caller—it made a weird noise—and he whittled it out of wood. When he blew into it, it made a noise just like a panther. He’d get down there and go across the river from that family and he blew that thing. They never did figure out what it was.

Grace: They were scared to death!

Hazel: This Mr. White Sherman, he had a sawmill up above our home. That was in the early ‘30s. He would haul logs and lumber. Lots and lots of nights they came along and picked us up. It was just a bare truck and they only made about five miles per hour. They had bars across the back to lay logs down. They would stop and pick us up and we would sit on top of the logs and then they would drop us off a half-mile away from our home.

I was riding up in the front with Mr. Sherman one night, and oh, he was a big tease, and he started teasing me. I was carrying a lunch bucket—I had too much lunch—Mother always packed plenty because kids at school would steal our lunch. And he started teasing me and I didn’t say anything. I reached in my lunch bucket and there was a cold biscuit in there and he opened his mouth to start teasing me, and I took that cold biscuit and put it in his mouth. I tell you, that old guy, he just about had a fit!

He just hollered and he said, “Boy you took care of me, didn’t you?”

We was pretty good-sized kids before we ever saw an automobile. We had a long bottom we always kept corn in it, and oh, it was probably a quarter of a mile to a half-mile. We were in the orchard playing and we looked down and saw this thing coming up—I can still see it—we didn’t know what in the world it was. And it was . . . who was it Grace?

Grace:

Uncle Campbell.

Grace:

Uncle Campbell.

Hazel: Our great uncle who had come to buy Daddy’s stock that he had for sale.

Grace: Well that’s a good ways back. We moved up there when I was five [1918].

Hazel: When the automobiles came out, there was something happening. I can’t remember what it was, but we were told, “Don’t you get into a car with nobody.” And we wouldn’t. So this man came along came along and he wanted to pick Grace up . . . Go ahead . . .

Grace: It was Uncle Campbell and his son. He wanted to buy cattle and he stopped and wanted us to ride, and we wouldn’t go. We went home and we told mom about it. About that time Dad and this Uncle Campbell was on the other side—we had a boat—and they come across and he said “There’s those children that wouldn’t get in the car and ride with us.”

Matthew: Was your mom mad?

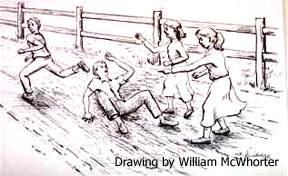

Grace: Oh no. She told us not to get in. She’d have probably given us a whooping if we had got in. Annie Shaffer: This is Hazel and Grace’s Mother. The river can be seen below. That is the old river road that she is on, and the normal floods would come up to that road, but the ’85 flood not only came over the road, it also destroyed their house above. Photo courtesy of Hazel Phillips

Hazel: When I was very small, I needed a pair of shoes, and there was no money to buy shoes. Mother took me down to Simpson Ford store, that was a general store, and they had shoes there, they were 29 cents and they had real pointed toes. That was a style then, but I hated them with a vengeance.

Mother tried them on me. She said, “Hazel will you wear these?”

I said, “No, I won’t wear them with them pointy toes.”

She said, “If I took those home and cut that cornered part off, would you wear them?”

I said, “Yes, if you cut

the point off I’ll wear them.”

She set down and ripped those back and took a knife and cut those toes off and I had the cutest little shoes: 29 cents! Flour was 25 cents for a twenty-five-pound bag. That lasted us one week. We always had biscuits for breakfast or we wouldn’t eat. And that done us a week. Think you could live like that?

We had a happy childhood. Sometimes we went to bed before dark and got up at daylight. If you was too little to hoe a row of corn, you was put in a row with the next youngest kid and the two of you hoed the row. That was the way of life. You raised your own food or you went hungry. There was a family there up above us; they took buckwheat cakes and apple butter to school for lunch . . .

We had a milk house—oh, it’s probably about half as big as this room, maybe smaller—and it sat right below the spring. When the spring overflowed, Daddy had a trough set up in the milk house and the water flowed through that trough. Mom would milk in the morning and after she strained it, she would take it up to the milk house to keep it cool so it wouldn’t sour. Then in the afternoon, if we got a thunderstorm, we had sour milk for supper. The thunderstorm caused it to sour. Why, I don’t know. But it did.

Grace: She had a stone jar and she would make her butter by the pound. She would cover it up and it would be just as firm as it could be. After we left home, they got a deep freezer and a refrigerator both.

-

Coleen Shaffer Parks: Grace and Hazel’s sister sitting above a small waterfall. Photo Courtesy Hazel Phillips

Hazel comments, “Those were the falls.

They were beautiful but they aren’t the same since the ’85 flood, its all filled

in. It used to be over your head before 85 and now it’s filled in, you can walk

all over it. And down at Pheasant Run, that’s right off of Shavers Fork, there

was a Sherl Kittle, and the Carr family lived there, Russ Carr family lived

there. And they heard this dog carrying on one night and the kids went outside

and they saw a body out there in the creek. And it was Sheryl Kittle’s body and

he had been murdered and they never did solve it. They suspected, one man went

to jail, but when it concluded they had to let him out.”

Hazel: Also in the fall, there was a family that went around and—they called it the threshing machine—and they went around and they threshed the oats from the stalk . . . and buckwheat and what else?

Grace: Dad had a big sickle. He’d lay it [grain] down and we’d go along and gather it up into a shock, like it would be about that high, and we’d tie something around it. And when the threshers come, then they’d put that to the thresh machine and put it in: buckwheat and oats. And some people raised wheat.

Hazel: They went, like, to Daddy’s farm today and then down to Canfields the next day. Everybody prepared a big meal. The women all come in to this woman’s house who was having the threshers that day and help cook. It was a chicken dinner because everybody had chicken.

Matt: One family had this thresher and they went around from house to house?

Hazel: They moved it. They always did it all in one day no matter where they went. And that next day, well, those women would go to the next house.

Fool’s Gold and River Crossings

Hayward Phillips (not directly related to Hazel Phillips), a resident of Parsons, recalls some of the interesting happenings in which his father was involved both as a child and as an adult:

My Dad found gold: it was fools gold. I guess someone had mentioned that they had seen some sparkling rocks. It was the late ‘20s that this happened. It was before my time or right as I was born.

My Dad told me stories about it, but I don’t know when they found it or how they found it. My uncle was the one who took people across the river, and he was the only one who made money on it. My Dad had to go to Washington a couple of times to buy shares to sell to people. And they did sell a couple. They made enough to pay everyone off.

He and my Uncle Elmer

was always into something. It didn’t surprise me at all that they was looking

for gold. I found out in high school and he and I started talking about it. I

don’t know if it says it there in the article, but it was assessed at $40 a ton,

and that’s not feasible then. Now that land is on government property. I wanted

to go and try to get some out of there, in my spare time, for my Dad’s benefit

anyhow, but I can’t.

Well, my Dad he told me about this one’s brother, his nickname was Chub. And he had a raft that he built himself, and he was just a kid. Fifteen-sixteen or so, and he handled the raft. He’d take them over for a dime or whatever people would give him. He was the only one who made money on the whole thing. People came in their frillies and all, and that was the most remarkable thing. Everybody in the eastern U.S. knew about the gold mine in Tucker County. That was the way they got out of debt for the gold mine. It was a big tourist attraction; they wanted to see the gold mine.

The Nail Run School in

Pettit. Doris and Jack Allender resided here until recently. There is no

evidence of Nail Run School at the county board of education.

Gathering Ginseng and Chestnuts

Hazel Phillips shares more stories about gathering from the forest:

We used to ginseng, and we would, these friends, Grace and I, we used to go. They had never been there and they wanted to go. And we went and walked right into it. Oh yeah. It was worth, I think—the last when we were kids at home—it was worth $15 dollars a pound. But you could come to town and buy a dozen eggs for a dime. That was big money. Ginseng looks a little bit like poison ivy. It’s got two little leaves and three big leaves and in the fall it has a bunch of big red berries in the center. You bury the seeds so they come up again next year. And you dig up the root.

Then, in the fall . . . at that time there were chestnuts. There were chestnuts everywhere. Everybody picked up chestnuts and Daddy took those with the horse and wagon over to Montrose and bought our fall clothes. He would sit us down and take a piece of paper and measure each of our feet. We didn’t get to go to the store. So that’s how we bought our shoes. We wore long underwear then. Our fall clothes were bought with the chestnuts. There was a store there in Montrose that bought them. It was near as far for him to go to Montrose as it was for him to go to Parsons.

I suppose they shipped them out, Of course, they shipped everything by rail then. But there was ten of us, and he bought all of our clothes with that. We used to get bags and bags of them. He took them in on a horse and wagon.

People also gathered plants for medicinal purposes.

Doris and Jack Allender tell about some of the curative plants that they harvested from the woods around their house, which was the old Nail Run Schoolhouse:

Doris: There’s ‘Balm of Gilead. It’s a tree, and when it buds you would take the sap and make stuff out of it for sores. And what other swamp-root did they used to use for the flu?

Jack: Boneset they used to use. It’ll kill pneumonia and the flu and stuff. The plant comes up and it has a white flower—always in the fall of the year leaves come out from the stalk—and they’d gather it up and hang it over the winter. During the wintertime, they’d take those leaves and make a tea with it, and the next day the cold or the flu would be gone. Strong! Boy. Nasty. Boy I remember tasting it one time!

Doris: I’ve gathered peppermint tea and stuff like that

Jack: At the spring of the year you can get these nettles. They’re real good. You cook them—green just like spinach—they got a good taste

Doris: I can tell you lots of plants to gather. There’s nettle, the young brier, violet leaves, doc, rock salad, Indian lettuce, watercress. And that’s all out in the wild—dandelion, poke, leeks.

Lucille Ward, who lived in Spruce, recalls slightly less natural treatments:

We mixed up a mixture of coal oil, kerosene and camphor—and a little bit of lard to keep it from blistering—and bathed it on them, the throat and chest. I believe a little bit of turpentine also. The lard had to keep it from blistering. My kids had a chance for whooping cough one time. We went out to Greenbank and got them the shots but that didn’t keep them from taking it, because we didn’t get it in time. So that’s what I used on them. And it was every night so they wouldn’t get bad. After a period of time, they got so used to it; they thought they had to have that to go to bed. I did it about three weeks. Whooping cough lasts a good while. It’s a cough, then you get so bad you can’t get your breath and cough. You draw in your breath—it makes a noise and it’s kind of scary—a lot of them would just cough and cough. But they didn’t get all that bad.

Hazel and Grace have a similar memory:

Hazel: Mother doctored us. I was taken to the doctor one time when I was a child! If we had a cold she would mix lard . . .

Grace: Lamp oil and turpentine, heated . . .

Hazel: A little bit of turpentine, heated it and put it on us real warm and put us in bed. Then sometimes if she could buy some whiskey. What did they call it? Homemade whiskey?

Grace: Oh . . . I don’t think she ever gave me that. She’d put a little piece of yarn-sock or a piece of muslin and put us to bed for the evening

Hazel: She mixed a little bit of whiskey with some brown sugar and something else for a cold-pneumonia compound. Ooh was it nasty. But boy, you’d wake up the next morning and your head would be opened up. She doctored us. Oh yeah. She knew a lot of the herbs. I remember this one time, a neighbor, I won’t name her, came to Mother and said she was pregnant and she was going to lose her baby.

Mother said, “Now just wait a minute. You just wait here. I’ll go get this one root.” And she went and got that root and she told her to make this one tea. The girl went home and drank the tea and it saved the baby. It saved it. Oh yes—them old timers—they knew. ‘Course we was too young to pay any attention . . .

“Doc Auville”

Shavers Fork was once home to one of America’s best violinists, although that’s not how many of the old timers remember him. Apparently he was also a famous herbalist, attracting patients from at least as far away as Pittsburgh, which is where he attracted one of his wives. (He had three, though not at the same time).

Doc Auville would cure folks from miles around and apparently got in trouble with the law at one point because of it. They dragged him down to the courthouse, but when they asked people if they would go to the clinic in Parsons to get medical attention and they said no, the judge let him go. After this trouble he formed the “Auville Biblical Health and Enlightenment Society” which a person had to join before receiving medical attention from Doc. What this did was allow him freedom of practice because of the separation of church and state. He used to quote the bible quite often, searching its pages for information about herbs that he could use in healing his patients.

Doc’s family originated from southern France, the DeAuville region. When his family came over, some shortened the name to Auville, and some further shortened it to simply Auvil. Doc was born in the Davis/Thomas area and spent his early manhood as a logger. One summer some gentlemen were touring the camps and at the end of the tour, Doc played the fiddle for them (he had taught himself to play to that point). The men apparently were connected to a school of music, and they offered him a scholarship to learn the violin. Doc spent his summers working as a logger, and the rest of the year learning to play classical music. Eventually he became so good that he was touring nationally and had his own school. The depression however ended that career for him, and he moved back to West Virginia where he became an herbalist for the locals.

Apparently his most common concoction used eggshells, which have a high concentration of calcium in them.

Lorraine Burke recalls growing up in Bemis and what happened when she got sick:

We went to the doctor in Durbin or in Elkins and they treated you for whatever it was. But my Grandmother had her own stuff. She kept a jar of smallpox scabs and would give each kid the scab and picked their arm and put the scab on their arm. I don’t know. People didn’t get sick as much as we do now. We didn’t eat as much junk. My mom canned 500 cans every year. We had our own icehouse with ice from the river. Got our stuff off the train from Elkins.

Dad would have us take crates apart and do all these chores. That’s how he kept us out of his hair. Dad would say, “Now kids, if you got the will, and if you got halfway some brains and a keg of nails, you can build anything in the world.” That was his attitude. He was very smart. We had the Bemis mercantile store. We had dry goods, groceries. We sold bottled medicines, and Dad would diagnose people himself. Now people baby themselves too much.

Gardening is another tradition that continues on the watershed today although on a smaller scale. Prior to logging companies “buying up” the hillsides, subsistence farms with very little cash flow occupied the area. People grew most of their own food and bartered for what they could not produce themselves.

Lillie Mae Isner recalls her family garden:

Oh man, we had everything you could imagine! We had potatoes . . . we had this big barn down there—we would get that thing full of potatoes—and we’d lay them on the barn floor and spread them out. They’d dry off and sometimes we’d take them and sell them. You know, take them in and exchange them at the grocery store. They won’t do that now. We could even take our eggs to town.

And butter. I churned butter and took butter

into

Wilfong’s market and got some change for food. Old Bill, he’d let you run

up a bill, and next week you’d pay up your bill. They don’t let you do that at

the grocery store anymore either! Wilfong would do that.

Wilfong’s market and got some change for food. Old Bill, he’d let you run

up a bill, and next week you’d pay up your bill. They don’t let you do that at

the grocery store anymore either! Wilfong would do that.

Fresh eggs. We’d take fresh eggs in there. We’d just exchange them or he’d give you the money for them. I don’t even have chickens anymore. We used to raise chickens and you’d buy fifty pounds and they’d give you fifty. It was a good way to sell feed. Then I’d butcher them every so often when the old ones got too old. I’d butcher them and can them. Then later on Howard got me a freezer. As we got older, we got things to work with.

Then we bought an old second-hand tractor. We used to do all that stuff with a horse and pitchfork. Ohh, I tell ya. I don’t know how we done it, but we did. The kids used to help too. Jake, he was a little bitty old thing, and we got that tractor. He was nine years old and his little feet would hardly reach the petals. He would rake. They wasn’t lazy kids, that’s for sure. Well, they was taught to work, not that they wanted to do it all the time, I don’t think. (laughs)

Well tended grave: This is a

particularly well tended grave that rests at the Isner family cemetery. Each

has a footstone that reads “Grandma” and “Grandpa.”

Courtesy Lillie Mae Isner

Hazel Phillips’ and Grace Gainer’s father had a mill. It was also worked by the Channells, and was perhaps the only steam powered grist mill in the state at one point. The mill could process as much as 2,000 bushels of buckwheat a year, and could operate in the dead of winter, when up to eighteen inches of ice covered the Shavers Fork. Standard charge was one gallon of rough grain for each bushel processed. Hazel explains: “There used to be a grist mill up there; now that was there before our time. And they came in the river and they made a canal where the water would, just a part of it would come down in the canal, so the water pressure would make the wheels go around to grind.”

In the early part of the twentieth century, a trip to the grocery store was a big event.

Grace Gainer recalls how the railroad helped ease this burden for a while:

I was born in 1919 and the train went out in 1929. We didn’t have any transportation except horse. They had a store in Porterwood and mother would make up her list. My brother, oldest brother Bray, would take the boat. He would cross the river and the engineer would blow when he was coming down. And if mother had an order, he would cross the river, and he’d put mother’s order on a stick. And when the engineer came by—he’d take the order—and then the next day when they came up they would set her order there beside the railroad track in front of the house. And then my brother would take the rowboat and go over and get her groceries. Now that’s how we got our groceries.

The railroads also brought in logging crews and the small farming communities along Lower Cheat experienced a big boom period while the timber companies stayed. Pettit was one of these communities that experienced a huge boom and then a sudden vacuum when the marketable timber was exhausted. The farmland remained, keeping the community intact, albeit on a much smaller scale.

Agnes Smith-Wilmoth, who passed away in 1982, wrote memoirs of her life in Pettit:

Pettit lies between two mountains and at one time was nice clean farms and good fences. There were big cornfields in the summer and good gardens. My mom planted rows and more rows of beans in the corn. And lots of pumpkins. She dried pumpkin and made pumpkin butter. I haven’t tasted the butter since she used to make it. She made elderberry butter and it was delicious.

The Frank Allender home is vacant now. It isn’t far from the cemetery. Once it was a nice place, but Pettit looks now like it did when the Indians roamed it. There is an Indian grave on Uncle Jake’s farm. Ed Frederick started to open it many years ago and lost his nerve after a little digging. No one bothered it after that.

On the Pennington farm, below the Hansford Cemetery, was a big ledge of rocks. The story goes that a poor family had no place to spend the winter so they lived under the rocks. And from that time on it was the Summerfield Rocks. They were close to the railroad that the Porterwood Lumber Company built in later years.

It is no disgrace to be poor but

very unhandy at times. How many people today would try to spend a

winter under

rocks sticking out of a hill?

winter under

rocks sticking out of a hill?

The pie social they had at Pettit years ago was a lot of fun. One time a pie sold for $30. One young man bought a pie, then the girl wouldn’t eat with him so he said, “By God, if its too dirty for you, then its too dirty for me.” And wham it hit the wall and there was pie everywhere. Two girls brought pies made with apple preserves and the buyers didn’t eat them. So they said, “We will put it in Dad’s lunch.” So it wasn’t wasted.

Young folks from miles away would come to the socials or to church, and they had to walk or ride horses. Now there are no young people where once there was so many. There are still houses in use that contain lumber sawed on my grandfather’s up and down sawmill, some at Parsons.

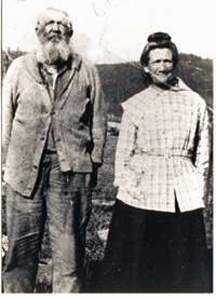

James M. Taylor & Lucebia N. Coberly, married November 5, 1874. Parents of Martha Ellen “Minnie” Taylor who married Burr Wilmoth in 1897. Burr and “Minnie” Taylor Wilmoth’s children are from oldest to youngest: Summa Willis, Clara, Waitman Taylor (Martin’s father, who married Gertrude Agnes Smith), Cammie Rebecca, Russell Alvin, Mary Belle, Sylvia Lena, Delbert James, Woodrow Wilson, Ruby Evelyn, Lucy Wanita. Photo courtesy Martin & Jean Wilmoth

“Them Vances, they were up there. Mrs.

Vance—she had a cow, sometimes two—and every day she would save me a pint of

cream. It was the same as eating ice cream, that’s what I thought it was.

Everyday she saved a pint of it for me. I called her Booboo, but her name

was Minnie. She was some lady. I didn’t even know what ice cream was. I

thought I was eating ice cream.”

—Leo Weese, an old Spruce resident.

Mysterious Lights Over Pettit

There were also reports of a strange incident in Pettit involving mysterious lights.

Agnes Smith-Wilmoth:

Pettit had its spooks too. I didn’t believe in ‘ghosts’ till I seen one. Before Frank Allender was married, he had to stay all week where he worked till Saturday night. One weekend on his way home, when he got to the “Old Parsons” cemetery below Pettit, a big bright light raised up and started toward the road.

Frank had been paid that day and he thought it was someone out to rob him. He started to walk faster and the light speeded up—so Frank started to run—and the light kept coming. When he landed at home he fell in the door and the light disappeared. In a few days, there was a death in the community and the light didn’t come back.

This is no Ripley Story!

On December 22, 1938, we was visiting at Allenders, and during the time we was there, it snowed hard. When we left at 9 o’clock, before we got in the car, I seen this big light coming towards us.

I said, “Wait, there is someone coming and might want a ride.”

Just a few feet from us it disappeared. So in the car we got and went down the road. There wasn’t a track to be seen. It looked like a big lantern and a big blaze in it. Several others saw it that evening.

The night before Christmas it was seen again. Fred Tusing shot at it several times but it was always moving and he didn’t hit it. At 2:30 on Christmas morning, Gay Summerfield’s dog kept barking so she got up and looked out the upstairs window. That light was coming down Pettit hill, and she got her children up to see it. Shortly after the New Year, Jesse Summerfield took sick and only lived three days. He said it was a “token” of death. It was never seen any more.

Old stove: Agnes Wilmoth’s old style wood stove. Jean Wilmoth says of her husband’s mother, “His mom made hot cakes for breakfast, biscuits for dinner, and cornbread for supper everyday. The whole top got hot. The hottest part was in the center there, and then you’d put it on the other side and it’d stay warm.”

Agnes was not the only Pettit resident to remember the light.

Jack Allender shares that his brother spotted it at one point as well:

Bob, my next to oldest brother, and Fred Tusing—the weather was bad or something—and they brought groceries from town, up there to a fellow by the name of Ray Shaffer’s Place, right there by the fork in the road. They went down there to get them. He was up there seeing Wanda, my next to oldest sister. They started down through there and they saw a light down at the bottom so they started walking down toward it. It was low down most of the time but high up some of the time and low down some of the time. And they got down there to the gate at the bottom; they had gone down the bottom road instead of the main road. Fred had an old pistol with him and Fred whipped it out and shot at it, shot at the light I reckon.

Bob says, “Oh my god, you better not shoot that. It might be someone running around with a lantern or something.”

And Fred said, “Well, they oughtn’t be going that darn fast.”

They followed it down the road until they got to the holler they call Aug Run. I think the government calls it Laurel Run but it was always called Aug Run by the old timers.

It went down in a great big circle and dropped down and ended up where Ray Shaffer lives. And that holler, it went on up and it went to the top of the road so they figured they’d see it again, but they didn’t see it then. They loaded up with their groceries and went back to the top of the hill and looked down, and it went around and curved that way. Fred took out it his pistol again and shot a couple times in the air. I think he was afraid to shoot at it after Bob had told him you better not shoot it because it might be somebody. They went on and I think it got out a little bit further and just disappeared.

And Bob said “That couldn’t have been no man. It went up over the gate like that, just up and down.”

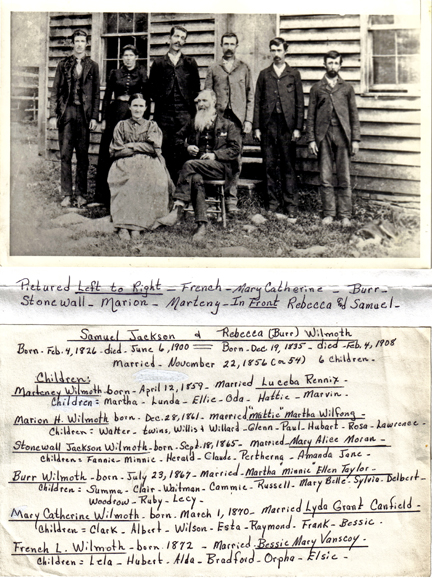

The Wilmoth family. From left to right

French, Mary Catherine, Burr (Martin’s Grandfather), Stonewall, Marion,

Marteny. In front Rebecca and Samuel Wilmoth. Photo was taken sometime before

1900. Photo courtesy Martin & Jean Wilmoth.

The Wilmoth family. From left to right

French, Mary Catherine, Burr (Martin’s Grandfather), Stonewall, Marion,

Marteny. In front Rebecca and Samuel Wilmoth. Photo was taken sometime before

1900. Photo courtesy Martin & Jean Wilmoth.

Blackberries and Old Bill

Hazel and Grace tell about another event and about farm life in general:

Hazel: There was several farms up around there that had been abandoned and they had orchards. When our trees didn’t hit, Grace used to go—I never did—but they used to go to these abandoned orchards on these farms and take the horses and bring the apples back.

Grace: Dad would take “Old Bill.” That was our family horse. You could do anything with him. He’d take two poles and put a harness on him and run those pulls up through the harness once we got up there. And then he put something across the harness, maybe put rope, and took them down over the hill like that. We’d pick blackberries. We’d go one place to pick blackberries where you’d have to scoot down. Mom would send white cloth with us and we’d pick them buckets full of blackberries. She’d tie them up around the top so if we fell we wouldn’t spill them. We canned a hundred quarts a year, with ten kids and two adults.

Hazel: We had this one old white dog we couldn’t live without. He’d play hide ‘n seek with us. He was one of the family. We’d even go up in the barn loft, and he’d come and climb the ladder and find us. It was summer, and he’d get too overheated and he’d jump the barnyard fence and go down over the hill. The river was right in front of our house. He’d jump in the river, get a drink and cool off, and then he’d come back and start hunting for us again.

Grace: Our Dad would take the two horses and he would take two of us kids with him—one in front of him and one in back and three of us older kids on Old Bill—took us to church every Sunday. When we got ready to go, Dad gave each one of us a penny to put in for Sunday school. That was big, putting a penny in there.

- Mt. Zion Repair: Volunteers with the Shavers Fork Coalition help repair the old Mt. Zion Church by filling the gaps in the log cabin and then caulking the gaps. Photo courtesy Shavers Fork Coalition

Church and a One-TV Town

Alice Cooper tells about growing up on a farm and about meeting her husband the old fashioned way:

My Dad was a farmer and had eleven kids. I was the eldest daughter. When my mom had a baby, I had to take care of her. I learned to cook when I was eight years old. My Dad taught me to cook. I’d stand in a chair at the stove and cook. I’d help out in the fields in the summer. We lived up in the head of a holler. Everybody went to church. Back then no one had a TV but this one old man, and everyone would gather up at his house on the weekends and watch TV. We’d play a lot of ball. I pitched. I played basketball when I went to school.

I met my husband at church. He was there with a friend of his and I was thirteen. He asked my Dad if he could take me home, and my Daddy said no.

He looked at me and said, “When you grow up, I am going to come back and marry you.”

When I was sixteen and in high school, I was walking down the street one day, and he walked up beside of me.

“I told you I was going to come back and marry you when you grew up.” He took my hand and kissed my finger right there and said, “I’m going to put a ring there.”

And he did. We were married thirty-eight years. I had his name wrote down on the Bible I had. I still have that Bible.

He said, “I never forgot you.” We’d just met those few seconds. I kind of had given up ever seeing him again. I lived up the head of a holler and he lived down toward town. He was seven years older than I was.

Down the river, Lillie Mae Isner talks about the cows and other animals that they used to have on the Isner family farm:

[Laughs] We had seven, but they were, I called them skruddy cows because they weren’t Jerseys, or they weren’t . . . My sister had a farm in Virginia, and she had one cow that give you all the milk you want! We’d milk all them cows and that was barely the same amount!

I said, “When Howard comes home I’m going to get me a milk cow.”

I did too. We didn’t have the modern stuff like they do today. But oh Lord, we had good times.

We had an old horse and it was something else. It got down and the vet came down and he said we had to get it up and walk it. We called it June.

“Well, the old horse is gonna die,” the vet said.

So we took June down to the river down below and tied it to the tree. That horse got loose and ran back to the house and lived for three more years. We always had a good laugh after that.

Well, I said, “Don’t let that die in the barn because it’s so much trouble getting it out.” ‘Course it died in the barn anyway.

Then I raised a little fawn. Yeah, Jake was down in the field and the Mother ran off. I guess the dog scared it. And he brought it to the house. Little tiny thing. I had to fix a nipple to the bottle to feed it. I called it Bambi, and so, when it got a little bigger, I let it out. I’d just bang the bottle on the fence, and man, it’d come a running from all directions. I got this dry milk from Southern States and mixed it up and that darn deer ate three bottles a day! And they were big ones. But I’d say “Bambi!” and tap on that fence and he’d a come a running. Little old tiny, slim legs—ain’t nothing to the thing.

Then somebody shot it hunting season ‘cause I didn’t fence it up. I just kept it in the house. Oh, I imagine two weeks until it was able to get around good. But it was so spoiled by that time. It’d just come get his food everyday. People in town knew I had it out here. They’d bring their kids out here and take pictures of it. I don’t think we’d have it now.

Jean & Martin Wilmoth, who lived on Slab Camp Run just off of Pheasant Run, also had wild deer as pets:

Jean: That’s the worst part of living here in Parsons: we don’t have our deer. They’d come right out and lay down by the fence to come out in the morning for the corn. See, the kids would just go down there and feed the deer, and they wouldn’t hurt them. We only had a four-foot fence around the garden. And them deer would come and stick their noses through the fence and smell but they never did jump over the fence and eat out of that garden. We had gangs of them, as many as twenty of them at one time. This was just this summer. I didn’t pet them too much but they’d let you pet them as much as you liked.

Martin: I had an old doe one time let me milk her just like a cow. My boy come from Desert Storm, and he wanted to see that. Three does came in that evening but she didn’t come. So I tried to milk one of the other does and boy did she kick me. She didn’t like that. But that one little buck we had he’d box with me. I put on a heavy cushion and he’d pop it something good. It was when he’d turn his head sideways that I’d get nervous.

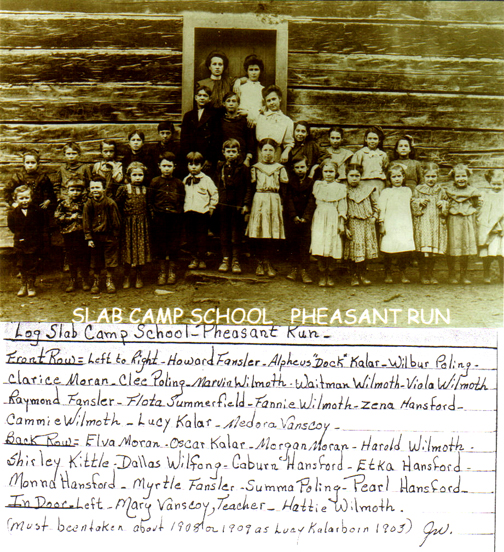

- Pheasant Run’s Slab Camp School, circa 1909. When the government was first making topographical maps, it accidentally renamed the run Pleasant Run. The name has stuck, although many locals still refer to it as Pheasant Run. Photo courtesy Martin & Jean Wilmoth

Old Poplar Barn

The forest around the Shavers Fork not only provided great wildlife but also produced great wood to build sturdy homes.

Jack Allender tells the tale of an old, well-made house:

One time, years ago, I used to be up in a holler called Nail Run Holler. But the first people up there . . . I don’t know . . . Wilmoth owned land up in there, but this one was between that. Anyway, it had a big log house on it, a big log barn, made out of what they call poplar. And in there, they had boards, about one-and-a-half foot thick, tongue and groove. I didn’t know they had that—they must have had tools to do it with—and planed it up smooth, smoother than today. I don’t know how they did do it.

But some crazy fellow went up there, long after the house was down but the barn was still up—it was up for years and years—and some fellow went in there hunting and started a fire. And it burned the barn down. But those old logs, they were straight as a board.

Like the old buildings, these old methods of subsistence living are disappearing. There are many places where you can still see the area’s history—from homesteads to evidence of logging camps and railroad grades—with everything in between.

Henry Nefflen tells about an interesting find:

I trap a lot and I had a few traps between the

road and the river—mostly trapping for land animals, a little bit of

anything—anyway, I had some coon traps and it was easy to check them. I looked

down and I saw this ring and I thought, what the heck is that?

I thought, what the heck is that?

It was all covered with leaves and the only reason you could see it was because of the snow. I found this ring and found some firebricks. Then I realized that there used to be a road going down here to a furnace. It might have been a forge working with horses but I don’t know what it was. It was round and it was made of pre-molded clay bricks. Nobody knows what was there.

Iceberg: July -1992 Near Petit W.Va.

Grace Gainer and Hazel Phillips (from left to right) standing next to what they

called the ‘Iceberg.’ Hazel explains, “And up in that hill, there is a big, big cliffed rock. This photo is from when my sister and I and two friends went up

there last, about 6 years ago, and in this rock, we called it the iceberg, you

could go up there until the 30th of May and dig the leaves out of

this one hole, and there was ice. And always the 30th of May someone

went to the iceberg and got some ice so Mother and Daddy could make ice cream.

We had an ice cream freezer, one you crank, and that was always the 30th

of May, someone got ice and we had ice cream, of course that was a big treat, to

a bunch of kids. It stayed there until way up into the summer. You could go

there and step there and feel this cold breeze coming out.”

Photo Courtesy

Hazel Phillips

Ramps

Ramps are one of the first things a person hears about after crossing the state line into West Virginia. Everyone knows about ramps and regards them with love or disdain or both. Occasionally called “spring tonic,” folks often love the taste of ramps, but hate the strong smell. Ramps are related to radishes but are more like onions. When raw, they rival garlic in potency of scent, and it’s said that a person who eats enough raw ramps will begin to smell just like them.

Chuck Hayhurst, a long-time Bowden-area camper, related that ramps are the first plants to emerge in the spring:

They are like an onion, from the onion family. The leaves are good; we cook the leaves and all. We go out here and dig ‘em. We pull them out. They grow out here near rocks. They are only good for two to two and a half months. After that they get so big you can’t eat ‘em. Later on, all at once, they just die off. And then next year, the ones that you didn’t kill come back again.

We freeze them. We put them in Ziploc bags and then put them into a plastic container, because boy, they will stink up your freezer. Every Good Friday that was a tradition, everybody in the camp would grab their shovel or mattock and go digging for ramps. It was a tradition. We don’t do it anymore. I can buy them for a dollar a bundle, and that’s way easier than going out in the woods and digging them up.